Britpop (a word composed of “British” and “pop”) is a sub-genre of alternative rock that was developed in the UK in the early 1990s. Not only was it seen by all as a reaction to the neurotic American grunge movement (Nirvana, Pearl Jam…), it was also a reaction to the ethereal and noisy style of shoegaze (My Bloody Valentine, Slowdive…), both appreciated by the British public in the early 90s.

In this way, Britpop intended to return to a more traditional rock style, characterized by guitar melodies, catchy pop choruses and a sound tailored for radio stations, while becoming the heir to a wide range of earlier English music. Bands such as Oasis, Pulp, Blur, Supergrass, Suede and Manic Street Preachers were the reason for the huge success of Britpop in the 1990s. Nevertheless, the genre went into commercial and critical decline around 1997 due to the lukewarm reception of Oasis’ third album, Be Here Now, following two exemplary albums, and Blur’s decision to distance itself from the genre.

The British press then focused on Radiohead and The Verve, considered more ambitious than their peers but less representative of the typical Britpop sound. Yet, at the turn of the millennium, bands with glory such as Coldplay, Travis and Doves gave a second wind to Britpop while not forgetting to show an international face. In this article of Gazettely, we want to introduce some of the most popular Britpop albums of the 1990s.

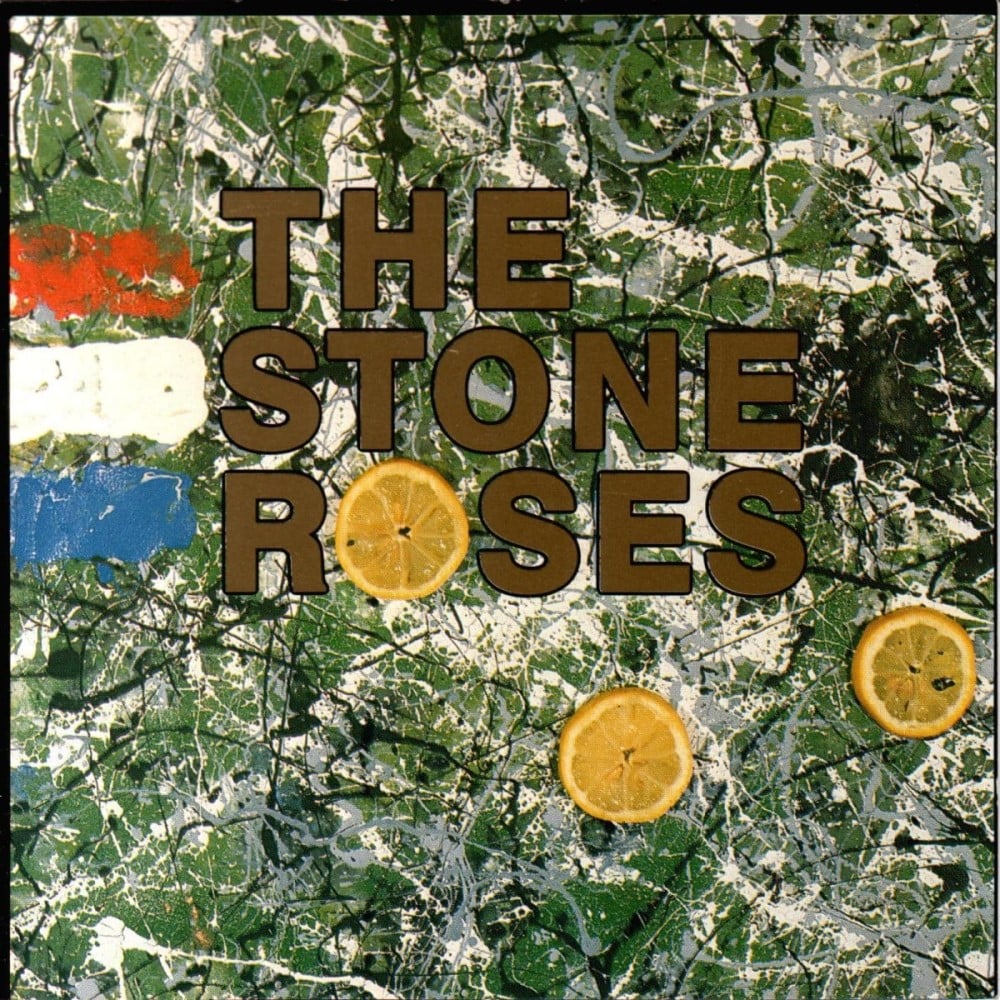

The basis of Britpop: The Stone Roses – “The Stone Roses” (1989)

Up until then, these had been unsteady, unsatisfactory years in British pop culture, devoid of direction and friction. Maggie Thatcher, who had long been a bogeyman of meaning and solidarity, was in the process of completely dismantling herself when factory owner and hacienda operator Tony Wilson, in a daring act of business acumen, went out on a limb and declared “Madchester” the center of the world. According to the smart Tony, pop’s future was its danceability, in conquering the dancefloor with guitars. And that is exactly what happened in Manchester.

In retrospect, this marketing gambit certainly proved to be a self-fulfilling prophecy and an object lesson in media manipulation. But the Stone Roses profited considerably from it. Not just because they landed respectable hits in the following months with “Elephant Stone”, “Made Of Stone”, and “One Love”. And not only because their album became a bestseller after all, but especially because they became the most important source of inspiration for an entire generation of musicians.

The Britpop generation. For nearly three years, they were considered the coolest band on the planet. Anything was imitated, everything from John Squire’s way of holding the guitar to Ian Brown’s waddle to Mani’s headgear and Reni’s pants. “Their style was as perfect as their timing,” Noel Gallagner recalls, “they were in the right place at the right moment.”

From new wave to “Father of Britpop”: Paul Weller – “Stanley Road” (1995)

Together with the Stone Roses, Paul Weller holds the title of “Father of Britpop.” After the successes with The Jam and The Style Council, he started working on his solo career in 1991, culminating with “Stanley Road” in 1995. Wellers third solo record went quadruple platinum in the UK and remains his most successful release to date.

However, it is less the sales figures that make “Stanley Road” a great album. It is rather the positivity conveyed and the joy of making music that one can’t help but feel when listening to it. Named after Weller’s street in Woking, England, this album serves as a clear reference to his British heritage. Occasionally reminiscent of Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop” from the album Rumours, its title track is Fleetwood Mac’s equivalent of Paul Weller’s “Stanley Road”: their opus magnum.

Also, when the album was released, the timing was gold. British pop was on the cusp of becoming absolutely mainstream in the united kingdom. Weller linked various eras of British pop history on “Stanley Road” on the one hand through his own person and on the other hand with guest musicians such as Steve Winwood and Noel Gallagher. Completing the release was artwork by Peter Blake, by none other than the designer of the “Sgt.Pepper’s” cover. He himself is still satisfied with the highlight of his career:

“We still play a lot of songs from “Stanley Road” live, which already says something about the longevity of the album. The first two solo albums are perhaps something like the prelude to this third. It all came together; it all fit. Because of all the concerts, I had enormous self-confidence when it came to playing, so the songs came as if by themselves. Once Noel Gallagher also came over, had a few glasses and then had to play along a bit.”

Morbid Britpop: Suede – “Dog Man Star” (1994)

SUEDE hated Britpop. Their lead singer Brett Anderson referred to those who emulated so-called laddism, personalizing the attitude of mid-’90s British pop culture as “social tourists.” Middle-class people posed as members of the lower class by yelling for a beer at the 1996 European soccer championships (“Lager! Lager!” as in the Underworld hit “Born Slippy”) or by paying homage; to the heroin chic of “Trainspotting.”

Anderson, who comes from the poorest of backgrounds, faced the unwelcome B-word with rigorous distaste: “Musicians who waved the British national flag in the nineties: That was not fashion, it was disgusting nationalism! A couple of idiots holding up the Union Jack on stage. Unfortunately, Britpop was nothing more than that.”

The fact that they were nevertheless elevated to the status of the “Big Four” of Britpop alongside Oasis, Blur and Pulp could not be avoided by Suede. In 1991, “Melody Maker,” which was influential on the island at the time, praised them as the greatest guitar pop musicians since the Smiths – and without having released a single song.

In 1994, they followed up their self-titled debut with “Dog Man Star”, soon after the first signs of life from various artists who were soon considered to be part of the Britpop scene. But Suede had an absolutely unique selling point: A mixture of glam rock, clown tears, the working class and drug-induced “Dungeons & Dragons” fantasies.

How awkwardly pop and classic can harmonize with each other was proven by Suede with the much-loved, orchestra-escorted song “Still Life”, which concludes “Dog Man Star” as a powerful finale. In a similar vein, the only song which could match them is Elbow’s “Mirrorball” from the outstanding album “The Seldom Seen Kid” (2008).

Britpop in a different guise: Blur – “Blur” (1997)

Among the reasons, Suede hated the label of Britpop was Blur. More specifically, Damon Albarn. Justine Frischmann, a founding member of Suede and later vocalist of Elastica, left Brett Anderson for Albarn. No need to say more. Millions of Blur fans, however, were less prejudiced.

In 1997, Blur had long been one of England’s biggest bands. Britpop hype was their platform, and their standing manifested over four albums in the early and mid-1990s, not the least of which was their rivalry and publicly displayed vying for higher sales with Oasis. However, in contrast to their biggest rivals from Manchester, Blur was willing to venture on their self-titled album.

Indeed, they turned away from their previous sound, one that had become their own trademark and that of the entire Britpop era. “Blur” was oriented toward American indie with lo-fi influences. Albarn and his fellow musicians squinted at dub (“Essex Dogs”) and took grunge for a ride with “Song 2.” Their bravery paid off, and “Blur” advanced to become the band’s most successful album. The step to leave the feel-good zone deserves respect.

Blur managed to achieve a breakthrough in the USA thanks to “Song 2”. Many of their British colleagues cut their teeth on it – Blur succeeded thanks to a misunderstood joke. As well as the success in America, the story of the song’s creation was more or less coincidental. With the album already finished, the band had a party in the studio. In the course of the festivities, they spontaneously played the song that made them famous even beyond the borders of Great Britain.

From Rubble: The Verve – “Urban Hymns” (1997)

“Urban Hymns” from The Verve appeared just like “Blur” after the real zenith of Britpop. In no way does it make the album worse. With its third album, the Wigan band said goodbye to shoegaze and set out to become one of the most defining British bands of the late ’90s. However before the biggest album in their history, The Verve went through a brief crisis.

Frontman Richard Ashcroft and guitarist Nick McCabe couldn’t bridge their differences, so The Verve ceased to exist in the meantime. Just a few weeks after the split, the group got back together – without McCabe, though. Ascroft remembered the strengths of the band and jumped over his shadow. He called up McCabe and asked him to rejoin The Verve after the remaining members realized that a key piece of the puzzle was missing without the former guitarist.

That hackneyed cliché of the phoenix rising from the ashes became a reality with The Verve and their breakthrough album “Urban Hymns.” The song “Neon Wilderness” still refers to the previous albums with their flat, dreamy guitar arrangements and psychedelic impact. “The Rolling People” and “Come On”, in contrast, are considerably more straightforward and help “Urban Hymns” to achieve a successful dynamic. This album is expansive without getting lost. It is structured without seeming stiff.

The only number one hit of The Verve is “The Drugs Don’t Work”, but the indisputably most famous song is and remains the album opener “Bittersweet Symphony”. The orchestral version of the Rolling Stones song “The Last Time” was used as a template for the world-famous orchestral sample – legal disputes included. At the latest, through the use of the song in the film “Ice Cold Angels”, “Bittersweet Symphony” became legendary.

Madness and bluster: Manic Street Preachers – “The Holy Bible” (1994)

This was Richey Edwards’ album and its last cry: a bunch of full-bodied quotes, philosophy not quite understood, a social romanticism, wordplay, late adolescent poetry and dislike of the world. Performing live, Edwards bounced around alongside the three musicians, infrequently in the picture; Poster Boy, Heretic, Martyr all at once.

According to Nicky Wire, in retrospect, Edwards would read five books in a week – the bassist, who had married in 1994 and liked to vacuum at home, was unable to keep up. Most lyrics came from Richey Edwards, which then threw the chunks to James Bradfield, which had to write the music to “Yes”, “Archives Of Pain”, and “Revol”. The vocalist remembers his first irritation.

“The Holy Bible” was the third work by the Manic Street Preachers; it was a call to arms after the bloated “Gold Against The Soul.” Realizing that “Generation Terrorists” provocation had quickly evaporated, the band was ready to take up arms. Now they draped themselves in desolate military rags draped with medals, Bradfield donned a bobble hat – and thus they rocked through English TV: “Faster,” “PCP,” “She Is Suffering.” Glastonbury. Readings. Guitars smashing. Revolution starts here.

It wasn’t all bluster, though. James Bradfield managed some of his finest songs to the difficult masses of lyrics, “She Is Suffering,” “Die In The Summertime,” the memorable riff of “Faster:” “I am stronger than Mensa, Miller and Mailer.” At the time, almost no one wanted to understand “The Holy Bible.”

Today, Britain’s music press celebrates the unwieldy pamphlet against consumerism, the United States and inertia as a triumph for the Welsh – though it was actually “Everything Must Go” that made the Manic Street Preachers universally popular. Richey Edwards had already disappeared by then, considered lost for years, and in the meantime reported dead.

When two argue, the third is happy: Pulp – “Different Class” (1995)

If one believes the master himself, the majority of the lyrics on this record were written within one night at the kitchen table, accompanied by a cheap bottle of brandy and emotional imbalance. That this method of working is often enough very fruitful, journalists as well as students should be known.

But in the case of “Different Class,” it led above all to an immense cohesiveness of content: Jarvis Cocker basically drew the milieu, as well as his own state of consciousness, which, as in the case of the highly underrated predecessor “His’n’Hers,” had been fed by all kinds of latently sexual flashbacks.

However, at the same time, it was also possible to recognize the ambivalence of the incipient success: Thus, in keeping with the old familiar Indiedisko hits “Common People” and “Disco 2000,” “Sorted For E’s & Wizz” deserves special mention: “Oh is this the way the future’s meant to feel / Or just 20,000 people standing in a field,” it says here.

In retrospect, the original intention was to be a study of the ravers’ milieu, but this can also be read as a description of the state of the successful live band Pulp, who succeeded in one thing above all with this record: deciding the duel between Blur and Oasis, which had been staged in the media in 1995, for themselves.

Everyone’s Favorite: Supergrass – “In It For The Money” (1997)

So Pulp won the argument between Blur and Oasis. In the midst of the factional strife of the mid-’90s, however, there was one connecting factor in the heat of the Britpop era: everybody loved Supergrass, no matter the various cultural, geographic, or whatever differences. Their sense of humor played a crucial role in this. They sold official lapel buttons later in their career that read “everyone’s second favorite band.” Everyone’s second favorite band. It would have been sooner for Oasis to make an album with Blur before you heard them say that phrase about themselves.

Supergrass could laugh at themselves. Other bands were making big announcements, either verbally, in the press, or musically, but the Oxford trio (later quartet) acknowledged the absurdity of being in a successful pop band. Indeed, their second album, “In It For The Money,” bore this madness in its very title.

Yet despite the name, the follow-up to their debut, “I Should Coco,” was comparatively serious. Increasingly, the lightheartedness made way for thoughtfulness and gentle melancholy, for example, in “It’s Not Me.” Actually, perhaps the most beautiful feature of the album is Supergrass’ humility: songs like “Cheapskate,” “Sun Hits The Sky”, and the rather raucous “Richard III” are distinct advances in their songwriting.

Their harmonies, arrangements and rhythms are more sophisticated than on “I Should Coco.” It was better than those of many of their contemporaries in Britpop anyway, but never triumphantly presented. All remains song- and thus album-serving, making “In It For The Money” one of the ten best Britpop records.

Digression into Britpop: Radiohead – “The Bends” (1995)

On “The Bends”, Radiohead already hinted at their penchant for the artificial. One can find Britpop moments in the band’s oeuvre on this album. However, dissatisfied opponents of this opinion may quickly raise their fingers. To be able to classify “The Bends properly”, one has to be aware of the genesis. Radiohead actually found themselves at a crossroads in their still-young career. After they failed to establish an original profile with their debut “Pablo Honey” (1993) and relied instead on post-pubescent college anthems like “Anyone Can Play Guitar,” the internal tensions threatened to divide the band.

Thom Yorke, especially, was dealing with bouts of depression. In retrospect, presumably the breeding ground for deadly sad and wonderful songs like “Fake Plastic Trees.” He was increasingly doubtful about the future of the band and pondered the sense and nonsense of continuing.

The record company set the initial release date for the end of 1994. Ultimately, this was an involuntary pressure tactic. As it became clear that the band would not come close to finishing, their record company pushed for a quick single to be released well in advance of the album release. However, that didn’t come to anything either.

Until November 1994, Radiohead, who shifted their location to the legendary Abbey Road studios for the last third of the sessions, fiddled with the songs. Johnny Greenwood progressed to become the craftsman of the sound. He randomly changed guitars, experimenting with amplitudes, increasingly becoming a creative sparring partner alongside Yorke.

It is perhaps precisely the stimulus of pressure to succeed and attrition that ultimately saved the band. The reputation of Radiohead in the pop-cultural canon was no longer the same after this album. Although their commercial peaks were still to come: They had gained backbone, and genius in their interplay was not merely hinted at, unlike on “Pablo Honey.”

The Definition of Britpop: Oasis – “(What’s The Story) Morning Glory?” (1995)

The second album by Oasis is one of the masterpieces of British pop history. It’s the third best-selling album in England after “St. Pepper’s” and Queen’s “Greatest Hits” and contains classics of worldwide significance with “Wonderwall,” “Champagne Supernova”, and “Don’t Look Back In Anger.”

Songs on “(What’s the Story)” provide a direct counterpoint to those on 1994’s debut album “Definitely Maybe.” “The Whole first album is about escape,” Noel Gallagher told ROLLING STONE in May 1996. “It’s about escaping the shitty, bland life in Manchester. That first album is about the dream of being a pop star in a band. The second album is about actually being a pop star in a band.”

Consistently cocky, in one of his first interviews, Noel said, “If you don’t want to be bigger than the Beatles as a band, then your band is just a hobby.” Bigger than the Beatles, Oasis certainly didn’t make it.

They still earned their place in the top box of pop nobility, though, and in large part because of “(What’s the Story) Morning Glory.” The album’s role in the context of Britpop almost becomes a minor matter. Clearly, that whole Blur thing was huge in 1995, but who gives a damn today? The music, the actual core, has remained, and that is a good thing.