The war between Russia and Ukraine has made Europe’s energy dependence on Russian gas and the consequences of this polluting currency on citizens’ lives even more evident. Energy is at the same time an instrument of blackmail for the western powers and one of the significant open issues for the future: in which way the conflict will change the energy policies in Europe and in the world? Will the war be the reason for the turn towards renewable energies or the alibi for the revival of coal and nuclear?

Table of Contents

The Numbers

The EU imports about 40% of its gas needs from Russia, and in 2021 26% of these supplies passed through Ukraine, the privileged corridor of gas from Siberia to the EU. Italy is, of the European countries, the one which makes the most use of natural gas as an energy source (it is 42.5% of the national energy mix): far more than France (17%) and Germany (26%), which can, however, count the former on nuclear power, and the second on coal and a more advanced renewables park than ours [ISPI data 2022].

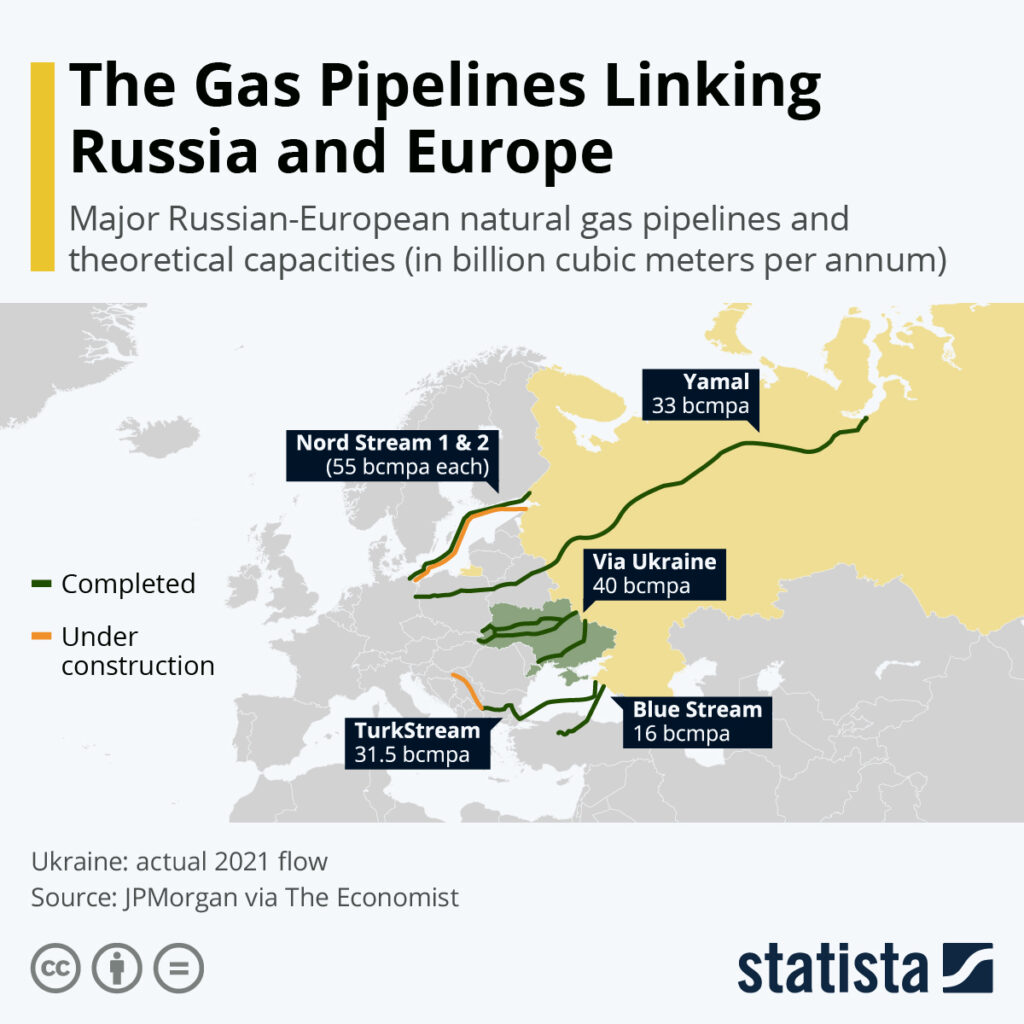

The infographics below show the routes of gas pipelines from Russia and their theoretical capacity in billions of cubic meters per year.

Natural Gas: How It Works

Natural gas is a fossil fuel composed of 90% methane (CH4) and the remainder of a mixture of hydrocarbons and other gases (nitrogen, propane, butane, CO2). This mixture, formed by the decomposition of biological material over millions of years, is located in reservoirs beneath the earth’s surface or under the seabed. It is less polluting than oil and coal (burning produces about half as much CO2, fewer sulfur oxides and particulate matter than coal).

This does not, though, render it a clean energy source. Natural gas is a greenhouse gas that, in the first 20 years after its release, has the power to trap heat 80 times higher than that of carbon dioxide, even if compared to CO2, survives less long in the atmosphere (a dozen years instead of hundreds). Natural gas extraction, storing, transportation and refining leaks from fields and distribution networks add to methane emissions from permafrost, farming and ranching and accelerate atmospheric warming.

Also Read:

- How Ukraine War Will End? These Are 7 Scenarios

- Top 17 Aircrafts of the Future

- What Is Quantum Physics?

An Important Customer

Lots of the European countries are amongst the main customers of Russian oil and gas. For example, every year Italy consumes between 70 and 80 billion cubic meters of methane gas, of which more than a third is imported from Russia.

For the ratio between total imported gas and total national consumption, Italy is, along with Germany, also one of the European countries most vulnerable to a possible interruption of gas supplies from Russia (it is worse for Moldova, Czech Republic, Belarus, Slovakia, which even if they import smaller quantities of gas, they all buy them from Russia and are even more dependent on these supplies).

As ISPI, the Italian Institute for International Policy Studies, explains, the issue of energy dependence on Russia is also structural and geographical: it is far easier to import gas via pipelines than by sea with LNG carriers, which carry liquefied natural gas (see below).

Realism or Disengagement?

To break free from Russian energy power and combat the climate crisis, there is a single, possible long-term solution: reducing the use of natural gas and transitioning to renewable energies. However, in the short-term, we may still compromise with polluting sources. European countries are moving to increase the purchase of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the leading producers, who in 2020 were the United States, Qatar and Australia.

LNG is a condensate of natural gas that makes it possible to reduce the volume of the substance by 600 times and store and transport it easily on LNG carriers and without the need for pipelines. At its destination, before being inserted into the national pipeline network, liquefied natural gas must be regasified, i.e. transformed from liquid to gas, in specific plants (Italy has three in operation).

Is It Ecological?

Although it arrives in a liquid state, it’s still methane: the climatic costs of this temporary “patch” would fall on the next generation (an infant today will be 78 years old in 2100). Without counting that in the United States, natural gas is extracted by fracking, artificial crushing of underground rocks through powerful injections of water, sand and a mix of chemicals, to release gas and hydrocarbons embedded in the porosity of the rocks underground.

Besides irreversibly marking the landscape, this technique has also been associated with high environmental and health risks (air pollution, the release of hazardous chemicals into the soil and groundwater, and induced seismicity).

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

The EU Commission has presented a plan to reduce dependence on Russian gas by two-thirds by the end of the year, which includes diversifying supplies (by importing more LNG and producing more biomethane, made from agricultural and industrial waste, and renewable hydrogen) and cutting industrial and domestic use of fossil fuels through energy efficiency and renewables. After a missed opportunity of the pandemic, this might be the right push to comply with the Green Deal, a plan to make Europe a net-zero emissions continent by 2050.

Not necessarily: According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), stellar gas and coal costs could lead to the reuse of European coal-fired power plants that have just closed or are due to close or the use of alternative fossil fuels (such as oil) in existing power plants. If that happens, we could say goodbye to the +1.5 °C of warming that we need to avoid climate catastrophe.

Meanwhile, the spectre of a new nuclear disaster in Ukraine does not desist from plans to open new plants in the Old Continent: in France, there is talk of a rebirth of the nuclear industry, with 6 new reactors to be built and another 8 under study, and Belgium and Germany, who had announced the exit from nuclear power, have done a U-turn by postponing the shutdown of their reactors.