Here, we see enzymes as the invisible stars of the biobased economy. These biocatalysts enable and control biochemical reactions – there would be no life without the protein molecules. The enzymes can be used as special tools to convert, break down or refine biobased products.

Enzymes are therefore indispensable helpers in food production. Still, these multitalented agents also perform key tasks in technical applications in the chemical, pharmaceuticals and paper industries. Enzymes are essential in detergents.

Without enzymes, research in molecular biology and many genetic engineering processes would not be possible. The dossier highlights the enormous variety of applications for enzymes and their potential for the bioeconomy.

Table of Contents

So what are enzymes?

They are complex protein molecules. Inside the body, such proteins act as accelerators of biochemical reactions. This is why enzymes are also called biocatalysts.

Enzymes are the central drivers of biochemical metabolic processes in organisms – no life without enzymes. All of these processes are controlled by enzymes, ranging from digestion to the energy metabolism of cells, from information transfer to the copying of genetic information.

They are special because enzymes are very specific – an individual enzyme usually catalyzes only one reaction. It converts only one specific molecule, the substrate. That makes enzymes special biological tools.

A massive variety of enzymes exist with a wide range of capabilities. For almost every biochemical reaction, nature’s toolbox has its own biocatalysts. Building, degrading or transforming molecules are the core functions of enzymes. Characteristically, the names of these enzymes end with “-ase”, i.e. cellulase, lipase or protease.

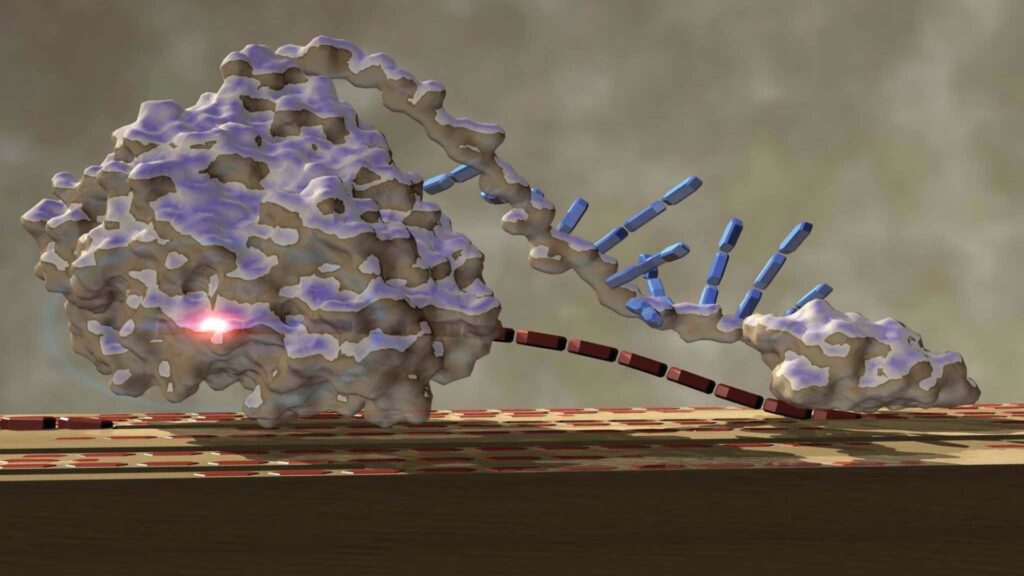

As typical for catalysts, enzymes support a reaction by bringing the reactants close together and increasing the reaction rate. They do not, however, form part of the resulting product. There is a region on the surface of the three-dimensional enzyme molecule where the substrate fits like a key in a lock.

The reaction takes place at this site – the active site. Afterwards, enzymes themselves are released unchanged and can immediately go into action with another substrate molecule. Being biomolecules, the enzymes are active under mild conditions (low temperatures, neutral pH, aqueous environment). And they are biodegradable.

People have long taken advantage of the extraordinary capabilities of enzymes. They have been used as important auxiliaries in the manufacture of biobased products. The food, feed and consumer goods industries would be inconceivable without these multi-talents.

In molecular biology research and breeding, too, they have a firm place as tools. However, enzymes are no longer the only tools biotechnologists rely on. Using the latest findings, they aim to design new types of biocatalysts or link them in cells to form new metabolic pathways.

Discovering and producing enzymes

Enzymes are the largest and most diverse group in the world of proteins. About 500 different enzymes are found in the well-researched bacterium Escherichia coli alone. Under international standards, around 5,400 different enzyme classes have been described in detail and systematically classified worldwide.

The BRENDA enzyme database, which was established in Germany 28 years ago and is operated in Braunschweig, is considered the world’s most important resource for biocatalysts. It archives information on 77,000 enzymes from more than 30,000 different organisms. Biology researchers are scouring global biodiversity searching for additional, hitherto unknown enzymes.

This search is greatly accelerated by powerful high-throughput technologies (“-omics”). High-throughput sequencing makes it possible to read sections of genetic material or even entire genomes from cell and tissue samples quickly and cost-effectively.

It is now even possible to sequence all the genetic information of a habitat, for example, a soil sample. This research field is called metagenomics. This makes it possible to track down the molecular blueprints of enzymes that cannot be cultivated in the laboratory.

Plants, Animals and Microorganisms as Sources

All enzymes are natural products. These are such complex and large biomolecules that they cannot be chemically reconstructed. They have to be created by biosynthesis and obtained from biological sources.

In the past, we extracted enzymes from animal or plant material. Among the most important sources were the pancreases of slaughter animals (e.g. detergent enzymes) and the stomachs of young calves and goats (rennet extraction for cheese). Since the mid-20th century, the focus has shifted to microorganisms as efficient producers of enzymes.

Bacteria, yeasts or molds are cultivated for this purpose in closed steel tanks – fermenters. Starch or other sugars are added to the liquid nutrient medium. Ideally, microbes grow and thrive, releasing the enzymes into the medium. Protein molecules are then harvested: The media is concentrated and filtered, with most enzyme preparations marketed as powders.

Transforming microbes into living enzyme factories

Initially, only the enzymes naturally produced by the respective bacterium could be used. In contrast, modern biotechnology and genetic engineering have opened up entirely new possibilities in this area. Genetic engineering methods can introduce the desired enzyme’s molecular blueprint into bacteria via so-called plasmids – tiny DNA rings.

The cells are thus converted and programmed to produce the added enzyme in high yield and purity. Today, most enzymes in the food industry and application technology are produced microbially with the aid of genetic engineering. Among the most important production organisms are bacteria of the genus Bacillus and molds of the genus Aspergillus.

Enzymes with improved properties

Biotechnologists ensure that their tiny high performers deliver their products constantly and consistently. Based on new microbiology and process engineering findings, the cell factories can be trimmed to peak performance. Novel molecular biology methods make it possible to design enzymes specifically for a particular application and thus improve them even further in terms of function (protein design).

Food industry: bread, cheese, juice and enzymes

As desired, enzymes, being biological tools, can modify starch, lipids, or proteins. Hence, versatile helpers are used in numerous manufacturing steps. Today, over 50 enzymes are used in the food industry. They enable more efficient use of resources, ensure and refine food quality, and improve shelf life.

Baked products

Enzymes are included in many bakery mixes these days. Especially in yeast dough and sourdough, enzymes help break down the starch in the flour into sugar, thus making it available to the yeast. Other enzymes break down the gluten protein.

According to the product, enzymes ensure optimum dough properties and reliable baking results. Enzymes help to add volume and color to the dough. They provide a beautiful and stable bread crumb. The now widely used baking of pre-produced, deep-frozen dough blanks would not even be possible without enzymes.

Dairy products

For milk to become cheese, its protein content must coagulate. Rennet ferment is traditionally used to thicken the milk. The substance occurs naturally in the stomachs of young calves and goats. It is now clear that rennet is a mixture of the enzymes chymosin and pepsin.

They cleave specific proteins (caseins) in milk and thus trigger coagulation. Before the advent of genetic engineering, these enzymes had to be extracted from calves’ stomachs at great expense. Molds or yeasts now take over production: They have been equipped with the chymosin gene isolated from calf stomachs and now produce the enzyme in large quantities and in high purity.

In cheese and other dairy products, Other enzymes such as lipases ensure the development of flavors and the formation of the desired texture. Lactase is also an important enzyme in the food industry: It ensures the cleavage of the milk sugar lactose. This enzyme is available in the form of tablets and capsules to enable people with lactose intolerance to consume dairy products.

Starch saccharification

Beet or cane sugar has long since ceased to be the only source of sugar. Basically, every starch-containing plant is capable of this (especially corn, potatoes, wheat). Enzymes such as amylase break down the long-chain starch into its molecular components during production – simple sugars such as glucose and dextrose.

With the aid of other enzymes such as isomerases, different sugar syrups containing fructose or maltose are produced in the further processing stage and can be used for sweetening.

Meat

Enzymes are also used in meat processing to influence structure, flavor and color. They are also used to join different cuts of meat together, e.g. in cooked ham (“enzymatic gluing”).

Beverages

Pectinases facilitate and improve the squeezing of fruits and vegetables by breaking down the cell walls of the plants more quickly, thus increasing the juice yield. In addition, they degrade any remaining turbidity to produce clear apple juice, for instance. Other enzymes ensure gluten-free beer.

As a rule, no labeling as an ingredient necessary

Food enzymes are generally used as additives in the manufacturing process in the food industry. However, in the course of the process, they are either removed or inactivated by heat. As they are not active in the final product, their use need not be labeled.

However, the enzymes invertase for keeping marzipan fresh and lysozyme as a preservative are also active in the end product as additives. They must therefore appear on the list of ingredients. Under an EU regulation from 2009, only those enzymes registered in a European Community list may be used in foods, and the Food Safety Authority EFSA checks for risks.

Special requirements do not exist for enzymes produced with the help of genetically modified microorganisms. They are subject to the same safety requirements as all other enzymes. A specific genetic engineering label is not prescribed.

Also Read:

Agriculture: better utilization of fodder

As additives in animal feed, phytase and xylanase enzymes improve the utilization of food by livestock. For example, phytase: this enzyme ensures that animals can better absorb phosphorus from plants. Nonruminants such as pigs and poultry cannot tap the vital nutrient phosphorus contained in plant food. As a result, phosphorus compounds must be fed extra by farmers.

However, phosphorus is a scarce resource. In turn, excess phosphorus ends up in manure and pollutes the environment. Adding phytase to the feed eliminates the need for supplemental feeding of phosphate, making dietary phosphorus available. Simultaneously, phosphate pollution of the environment decreases when manure is used as fertilizer.

With the aid of biotechnological processes, in the meantime, it has become possible to produce the enzyme phytase on a large scale using mold cultures of the genera Aspergillus or Trichoderma.

Technical applications: Washing, bleaching, tanning

In many technical applications and in the household, there is a demand for enzymes as problem solvers. Enzymes remove dirt during washing, assist in producing paper and textiles, and allow specific synthesis processes in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. Even in biosprite production, the enzymes are central players.

Washing

In detergents, the enzymes are indispensable helpers. Since they are highly effective even in minute quantities and become active at low temperatures, they have been largely responsible for reducing average detergent consumption and washing temperatures in recent decades. Forty percent of industrially produced enzymes are used in detergents and cleaning agents.

Proteases such as subtilisins ensure the degradation of proteins, i. e. they remove stains from blood, cocoa or egg. In turn, sauce residues are broken down by amylases, and fats are decomposed by lipases. They nibble at tiny nodules or protruding microfibers in the cotton fabric, thereby preventing textiles’ “graying”. There are also enzymes in cleaning agents for dishwashers or the cleaning fluid of contact lenses.

Processing textiles

Textiles can also be bleached with the enzyme catalase instead of hydrogen peroxide under mild conditions and with little energy input. Cellulases, in turn, are used to achieve the so-called “stonewashed” effect in jeans production. In this case, biocatalysts replace conventional production based on pumice stones.

Tanning

In leather treatment, enzymes are also in demand. Here, proteases are used to break down certain proteins in the leather hide of animals. Only the fiber-like protein collagen may not be broken down. Through the action of the enzymes, leather becomes supple and easier to dye in the course of processing.

Paper production

In the paper and pulp industry, we use enzymes to improve the mechanical defibering of the raw material wood. Another step in paper production, bleaching, also uses xylanases upstream. When paper is recycled, printing ink can be removed more easily with the help of cellulases and lipases (“deinking”). Enzymes help to reduce energy and resource consumption.

Producing biofuels

Enzymes are used to produce both first-generation biofuels (fuel from starchy fruits) and second-generation biofuels (fuel from agricultural residues). If wood or straw is the raw material for biofuel production, then cellulases and other enzymes ensure that the lignocellulose from the plant fibers is broken down into its individual building blocks. In the end, glucose is produced as a sugar molecule, which can then be fermented by yeasts to produce ethanol.

Synthesizing active ingredients

The pharmaceutical industry is also looking to enzymes as molecular “master builders”: Biocatalysis can be used to quickly and inexpensively produce molecules that are difficult or impossible to create by chemical synthesis.

This capability is used in the pharmaceutical industry to produce chiral drugs. Chiral drugs are active ingredients that only function as desired in a specific 3D architecture. The so-called enantiomer-selective catalysis is one of the enzymes’ great strengths.

Tools for molecular biologists and breeders

Not only are enzymes important as versatile helpers in industrial production. They are essential tools in molecular biology research.

A molecular toolbox

Restriction enzymes recognize and cut DNA at sites with a specific genetic letter code. The molecular scissors can be used to cut pieces of genetic material to fit. Ligases, in turn, allow the tailor-made DNA pieces to be glued together. Genetic engineering would be unthinkable without these tools. Taq polymerase is another standard enzyme used in laboratories.

This was once isolated from the bacterium Thermus aquaticus. This microbe lives in a 90-degree geyser in Yellowstone Park in California. The Taq polymerase is a copying enzyme needed to amplify DNA molecules in the polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

A further revolutionary discovery is also based on an enzyme: the CRISPR-Cas9 programmable gene scissors. It is a molecular precision tool that can be edited particularly easily and precisely by genetic material in living cells. The microbiologists found what they were looking for in the bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes. It has evolved into a molecular defense system against viruses. Scientists have optimized this CRISPR-Cas9 system for biotechnological applications and created a so-called designer nuclease.

A revolutionary gene shear

In the system, Cas9 is the actual gene scissors – acting as a nuclease, it can induce double-strand breaks in the DNA hereditary molecule. Through the CRISPR system, they can be programmed to make their cuts at defined points in the genome. This allows mutations to be inserted into the genome at many points simultaneously, segments to be cut out, or DNA fragments to be inserted.

In this context, molecular biologists refer to genome editing. Besides CRISPR-Cas9, there are other designer nucleases. However due to its ease of use, CRISPR-Cas has rapidly found its way into laboratories. Though only described in 2012, it is already emerging that it is not only transforming basic research. For breeding crops and livestock, too, this technology holds enormous potential. It opens up new possibilities for research into diseases and novel gene therapies.

Engineering new metabolic pathways

At the beginning of molecular biotechnology, production organisms were equipped with the additional blueprint for a single protein. In the meantime, scientists have succeeded in designing complex metabolic pathways with numerous enzymatic synthesis steps, equipping cells with them, and in producing industrial products in this way.

In this metabolic engineering, the researchers use genetic control elements and biosynthesis genes of different origins – for example, plants, animals or microorganisms. This specific construction of metabolic pathways and cell factories that do not occur in nature in this way is also known as synthetic biology.

Economic potential

Enzymes have become an important mainstay of industrial biotechnology. The AMFEP association of enzyme manufacturers alone lists around 250 enzymes that are sold commercially. Biocatalysts were used in the following sectors in 2010 (according to Sahm et al. “Industrial Microbiology”):

- 29% food

- 19% animal feed

- 23% detergents

- 29% other applications (textile, biofuels, paper etc.)

The production of enzymes occurs to a very large extent in Europe, as stated in the Bio4U study commissioned by the European Commission and carried out by the Joint Research Centre in 2007. The study found that 80 of the world’s 117 manufacturers are headquartered in Europe. Moreover, 64% of the world’s enzyme production occurs here, largely in Denmark, France and Germany.

According to a German source, in 2016, there were around 20 enzyme producers among the dedicated biotechnology companies in Germany. A major producer in this country is BASF. In turn, chemical company Henkel uses enzymes produced by contract manufacturers on a large scale in its detergents.

The prominent Danish producer Novozymes estimates that worldwide sales of industrial enzymes totaled around 3.3 billion euros in 2015. This company accounts for almost half of global sales (48%). The other enzyme giants on the global market include the U.S. firm DuPont (20%) and the Dutch company DSM.