From the sacred corridors of the Vatican to the dimly lit byways of Rome, an insidious force slithers – a primordial malevolence seeking an unholy vessel to birth its foul progeny. The First Omen unfurls like a sinister invocation, each frame dripping with dread and blasphemous purpose. As this ominous prequel to the 1976 horror classic weaves its intricate yarn, we bear witness to the cosmic machinations that preceded young Damien Thorn’s arrival – an event so catastrophic, it shook the foundations of faith itself.

Woven through director Arkasha Stevenson’s harrowing descent into ecclesiastical depravity is Margaret Daino’s harrowing personal odyssey. This virginal American novitiate, portrayed with a haunting vulnerability by Nell Tiger Free, finds herself ensnared in an ancient conspiracy to deliver unto the world the Antichrist’s unholy spawn. With each shocking revelation, the sanctity of her once-unshakable beliefs crumbles before a grand guignol of grotesqueries that would cause even Hieronymus Bosch to avert his gaze.

Demonic Lineage

To grasp the full, blasphemous scope of The First Omen, one must first understand its wicked lineage. In 1976, director Richard Donner unleashed upon the world his apocalyptic masterwork, The Omen, introducing audiences to the chilling specter of Damien Thorn – the Antichrist made flesh. This diabolical tale of an unsuspecting couple who adopt the spawn of Satan itself left an indelible mark upon the horror genre.

Over the ensuing decades, a trickle of sequels sought to expand Damien’s ominous origins, from the underrated Damien: Omen II to the schlockier efforts that followed. Yet none possessed the unholy inspiration of Stevenson’s rapturously wicked prequel. With painstaking craft, she has reverse-engineered the mythos, drawing back the veil to expose the eldritch rites and profane conspiracies underpinning Damien’s immaculate deception.

Like a cinematic paradox, The First Omen simultaneously pays reverent homage to its predecessor while charting terrifying new depths of sacrilege. It is an audacious origin story decades in the birthing – a transgressive reclamation of evil’s genesis that bolsters the Omen legacy as a seminal franchise in the pantheon of modern religious horror.

Descent into Madness

The unhallowed events unfurl in 1971 Rome, where sheltered American novitiate Margaret Daino arrives to serve at the ancient Vizzardeli Orphanage. Though welcomed by her mentor Cardinal Lawrence, a frostier reception awaits from the institution’s severe mother superior, Sister Silva. Margaret finds solace in the orphan Carlita, whose haunted artwork and disturbing visions mirror her own troubled past.

As Margaret forges a protective bond with Carlita, eerie incidents begin plaguing the orphanage. A disgraced priest, Father Brennan, attempts to warn her of an insidious scheme – one involving unholy ceremonies enacted upon the orphans themselves. Margaret’s concerns are dismissed as hysteria by the clergy…until a horrific discovery shatters her faith entirely.

Trapped in a waking nightmare, Margaret is forced to confront the heinous truth: the orphanage has served for centuries as an incubator, cultivating vessels to birth the Antichrist’s spawn. As her desperation escalates, so too do the film’s shocks and narrative twists. No one is to be trusted, from Margaret’s own free-spirited roommate Luz to the charismatic yet shady Father Gabriel.

Stevenson employs a slow-burn dread, each agonizing revelation and grotesque act of blasphemy compounding Margaret’s panic. Visions, both real and imagined, intermingle to erode her grip on reality. All the while, dark forces circle ever closer to their ultimate, apocalyptic aim – the birth of Damien Thorn himself.

Blasphemous Allegories

While superficially a chilling descent into supernatural horror, The First Omen resonates most profoundly as a subversive allegory for contemporary sociopolitical ills. Arkasha Stevenson wields her cinematic scalpel with brutal precision, laying bare the malignant perversions festering within institutionalized faith and patriarchal dominion over the female form.

Central to this apocalyptic fable is the subjugation and violation of female bodily autonomy – a disquieting mirror to recent assaults on reproductive rights. The orphanage’s conspiracy hinges on using Margaret and the other novices as unwitting vectors, their bodies coldly conscripted to serve as incubators for Damien’s unholy gestation. Each lurid, visceral atrocity committed against them represents a metaphorical desecration of self-determinism.

Yet it is not merely the sexual commodification of these women that Stevenson’s scorching lens captures, but the obliteration of their entire existential identity. The depraved clergy festishion existential prisons, seeking to reduce their wards to mere spiritual vessels divorced from agency or individual will. Margaret’s agonizing journey parallels a feminist awakening to the oppressive dogma calcifying the church’s very bones.

No less scathing is the film’s portrayal of corrupted religious authority as an ouroboros of moral bankruptcy. The conceit of unleashing the Antichrist to “save” Catholicism from declining adherence is a darkly satirical jab at institutional desperation to retain paleolithic dominance. The gradual revelation that even moral pillars like Cardinal Lawrence are compromised creates a spiritual void – a radically destabilizing void where neither faith nor dogma can be trusted.

Through her haunting visuals and escalating atrocities, Stevenson posits that true darkness lies not in scriptural bogeymen like Damien, but in the human impulses that viralize misogyny, subjugation, and the perversion of sacred principles as weapons of social control. The First Omen chills to the bone, yet leaves us wondering who the real “evil” ones are.

Cinematic Sacrilege

To conjure such an intricate tapestry of unholy dread requires not merely a steady narrative hand, but a boldly transgressive eye for visceral aesthetics. In this regard, Arkasha Stevenson demonstrates a masterful control of her cinematic domain. The First Omen is a baroque nightmare etched in chiaroscuro, with the shadow of the cosmic abyss tainting even its most luminous frames.

From the haunting, labyrinthine corridors of the Vizzardeli Orphanage to the lurid, strobe-lit decadence of Rome’s nightlife underbelly, Stevenson and her team have immersively recreated 1970s Italy with exacting period fidelity. Every dimly-lit chamber and crumbling architectural antiquity exudes a palpable sense of history and place, rooting the supernatural proceedings in an authentically grimy, earthly realm.

Complementing this exquisite production design is the masterful camerawork of Aaron Morton, whose lens appears possessed by the very daemonic forces it captures. Prowling steadicam shots insidiously stalk Margaret through the orphanage’s umbilical innards before rupturing into jolting phantasmagorias of bodily violation. Morton’s framing often embraces the oblique and disorienting, plunging the viewer into Margaret’s skewed perception with dizzying Dutch angles and fragmented planes of reality.

No appreciator of the cinematic form can ignore Mark Korven’s dread-inducing score, which corrupts the traditional sacral chorus into a profane marriage of the celestial and the damned. Hymnal vocal refrains swell in dissonant counterpoint to gnashing, percussive eruptions akin to primal tantric rituals. Even sequences devoid of Korven’s godless melodies thrum with a palpable, atmospheric dread.

Yet for all this technical galvanization, it is perhaps Stevenson’s feverish grasp of aestheticized body horror that emerges as The First Omen’s most singularly unsettling achievement. From the surreal, Cronenbergian nightmare of an unholy birth to graphically protracted depictions of self-mutilation, the film transcends tawdry shock value. Each setpiece of corporeal desecration serves to externalize Margaret’s psychological and existential violation in excruciatingly tactile terms.

Like the most subversive elevated horror, The First Omen deploys its atrocities with equal measures revulsion and artful reverence. Beneath the blood, viscera and shattered penances lies a rich iconography of sacrilegious subversion awaiting any brave enough to embrace its unholy mysteries.

Damning Flaws

As masterfully as The First Omen weaves its apocalyptic tapestry, even the most finely-wrought sacrilege is not without its damning flaws. For all its transgressive brilliance, Stevenson’s film occasionally stumbles into the well-trod pitfalls plaguing modern horror.

Cheesy jolts and cheap shocks, alas, remain inescapable rites in the genre’s current zeitgeist. The First Omen punctuates its dread-soaked atmospherics with an overabundance of jarring stinger cues, with even innocuous moments like Margaret being touched on the shoulder heralded by a cacophony of shrieking music cues. This transparent startle-tactic ultimately defangs the more impactful frights.

Narrative convolution also rears its muddled head in the film’s final act. As obligatory franchise setup kicks in, plot revelations arrive in a tangled, expository rush that disrupts Stevenson’s patient escalation of madness. Crucial character motivations become obtuse, with even primary players like the scheming Cardinal Lawrence devolving into opaque ciphers spouting biblical hokum about defeating sin itself – a narrative detour dangerously close to the sort of proselytizing didacticism this creative team has otherwise avoided.

More damningly, the climax relies heavily on nostalgia callbacks to the 1976 original that, while initially clever, ultimately undermine The First Omen’s unique ambitions. One can’t shake the feeling that the entire ingenious endeavor has been reductively repackaged as an overqualified prologue – a suggestive preface that never quite transcends its obligatory fealty to an increasingly dated franchise framework.

These creative fumbles prove all the more frustrating given how seamlessly rich and self-contained The First Omen’s horrors initially unfurl. Not until its final spasms does this unholy birth labor under the crushing expectations of an Omen legacy perhaps better left undisturbed by prequelitis.

Possessed Thespians

For a film so steeped in the profane, it is perhaps only fitting that the performances within The First Omen feel divinely possessed – fevered embodiments of humanity’s capacity for both grace and damnation. At the haunting center is Nell Tiger Free, whose soulful portrayal of the ill-fated Margaret Daino encapsulates every dimension of existential torture.

Free’s transformative journey from meek novitiate to unraveled apostate burns with a quiet intensity. Her delicate features contort from innocence to shattered disillusionment, each new blasphemy chipping away at her spiritual moorings. Yet Free imbues Margaret with an almost feral resilience, her naked determination to protect the disturbed orphan Carlita radiating maternal ferocity.

The young Nicole Sorace matches Free’s anguished commitment as the unsettling yet vulnerable Carlita. Sorace’s hollow-eyed presence seamlessly oscillates between unnerving inscrutability and heartrending fragility – a masterclass in cultivating uneasy empathy. Her enmeshment with Free forges the film’s pounding, maternal heartbeat.

The stellar supporting ensemble each emblazons the proceedings with exquisitely pitched depravity. As the disgraced Father Brennan, Ralph Ineson manifests pure apocalyptic zeal – a harrowing portrait of faith’s descent into raving madness. Veteran Brazilian actress Sônia Braga smolders with frigid malevolence as the orphanage’s austere Mother Superior, Sister Silva.

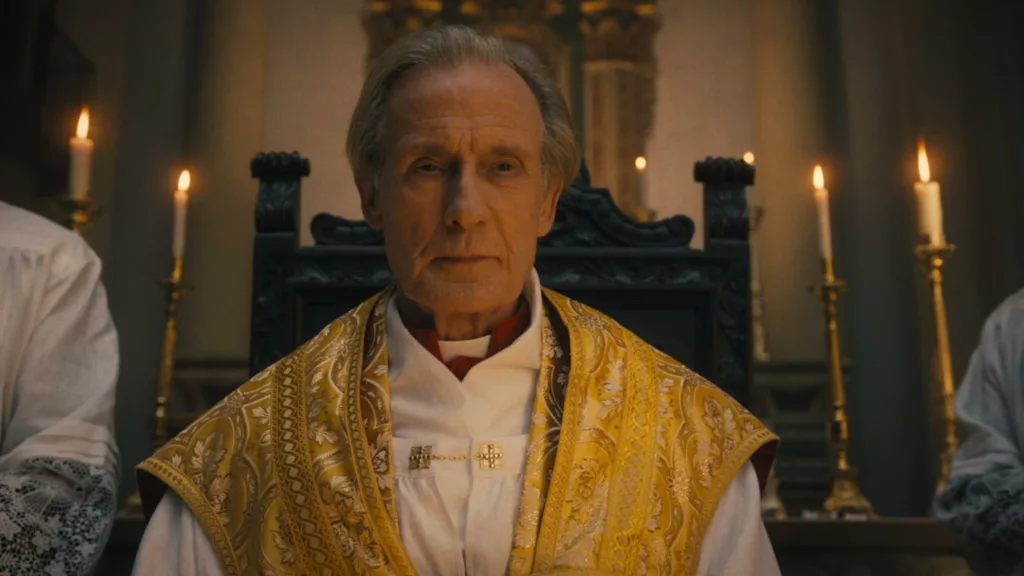

In limited yet memorable turns, Bill Nighy and Charles Dance each leave indelible marks as members of the treacherous clergy. Nighy’s Cardinal Lawrence cloaks his sinister machinations beneath an oily charisma, while Dance’s Father Harris meets his iconically grisly fate with a solemnity befitting The Omen’s legacy of elaborate “accidents.”

It is perhaps Maria Caballero as the vivacious Luz Velez, Margaret’s worldly roommate, who most vividly embodies The First Omen’s dueling constructs of the sacred and profane. One moment a liberating force of feminine joie de vivre, the next an agent of horrific violation – her duality epitomizes the film’s thematic dichotomies in flesh and spirit.

Blasphemous Birth and Hellish Afterlife

In regards to The First Omen’s broader legacy and cultural resonance, only the sands of time will unveil whether Arkasha Stevenson’s profane creation manages to breathe new unholy life into a long-dormant franchise, or simply rouse a new generation’s curiosity in seeking out Richard Donner’s 1976 original.

This much is certain – in this era of perpetual recycling and regurgitation, The First Omen distinguishes itself as a rare instance where a legacy property has been exhumed not merely for corporatized nostalgia, but with an artist’s subversive intent burning at its core. For every dutiful acknowledgement paid to The Omen’s iconography, Stevenson counterbalances with jolting innovations in body horror and thematic transgression.

There can be no debate that the lurid, grandiose atrocities etched across The First Omen’s deliriously blasphemous canvas will cast long, indelible shadows. Its searing visuals are the stuff of forever-scorched retinas, destined to be quoted and dissected by horror aficionados for decades to come. For fans of the ecclesiastical horror subgenre, it instantly enshrines itself as a seminal text.

Whether this perverse genesis achieves a similar degree of mainstream cultural penetration akin to its progenitor remains far murkier. The original Omen was very much a product of its era – a time when archetypal forces of evil could still scan as universally menacing rather than niche. In today’s increasingly secularized zeitgeist, Stevenson’s funhouse of sacrilege may scan as too obscure or dogmatically steeped for widespread impact beyond devoted circles.

Then again, perhaps it is this very unwavering commitment to doubling down on ecclesiastical extremity that will galvanize The First Omen’s cult footprint. Whispers of its visceral, uncompromising ferocity have already generated a feverish buzz among genre enthusiasts starved for unrated, unchained cinematic depravity. As pre-existing properties become increasingly play-it-safe and consumer-tested, the raw belligerence of Stevenson’s birthing rites may well achieve a infamously rarefied air all its own.

In the end, The First Omen represents a new sort of horror milestone. It is a work of such singularly unrestrained vision and technical bravura, so feverishly steeped in taboo-obliterating madness, that it transcends pedestrian notions of genre entertainment. No, what Stevenson and her team have summoned here is nothing less than a full-bore cinematic ritual – an ecstasy of profanity designed to purge, lacerate and ultimately prepare audiences to embrace a new, all-consuming wave of unholy fear. There will be blood, there will be desecration, and you will believe in the Antichrist’s coming like never before.

The Review

The First Omen

The First Omen is a sacrilegious descent into the blackest depths of religious horror - a feverishly blasphemous labor of boundary-obliterating depravity. With an unholy marriage of indelible visuals and thematic transgression, director Arkasha Stevenson has reversed the curse on a long-dormant franchise, breathing profane new life into its desiccated canon. For those brave enough to embrace its ecclesiastical extremities, this unrepentantly vicious prequel is nothing short of a subversive, unsettling masterwork - a grand guignol of grotesqueries designed to purge, lacerate, and corrupt. Genuflect before its terrifying rebirth, lest ye be forever damned.

PROS

- Stylish and visceral direction from Arkasha Stevenson

- Haunting lead performance by Nell Tiger Free

- Transgressive themes exploring female oppression and religious hypocrisy

- Exquisite period production design and cinematography

- Shocking and memorable body horror sequences

- Reverent homages to the original Omen while forging its own identity

CONS

- Over-reliance on cheap jump scares/stinger cues

- Convoluted plotting and character motivations in the final act

- Obtrusive franchise setup diminishes its individuality

- Increasingly niche premise may limit mainstream appeal