The Plague, Charlie Polinger’s debut feature, premiered in Cannes’ Un Certain Regard sidebar in 2025. Set in the sweltering summer of 2003, it follows 12-year-old Ben (Everett Blunck) as he navigates the rigid pecking order of an elite water polo camp. Polinger (writer-director) and cinematographer Steve Breckon conjure an aquatic netherworld—slow-motion dives become rites of initiation—while Johan Lenox’s score (distorted vocal stutters, abrupt silences) underscores the psychic frictions beneath youthful bravado.

At the heart lies a fabricated malady: “the plague,” a supposed contagion marked by pimples that binds the group’s unwritten code. Touch Eli (Kenny Rasmussen), the outcast, and you must scrub yourself raw—an absurd ritual that mirrors witch-hunt dynamics in broader society (see McCarthyism circa 1950s, minus the subpoenas). The film’s coming-of-age drama and psychological horror merge into a single current, carrying us from casual cruelty to visceral dread.

Blunck’s Ben oscillates between craving acceptance and recoiling at groupthink; Kayo Martin’s Jake wields observation like a scalpel, dissecting his peers’ weaknesses. Joel Edgerton turns up as the well-meaning yet ineffectual coach, Daddy Wags, a reminder that adult authority can be as blind as it is distant. In under 200 words, Polinger lays the foundation for a study of conformity, othering, and the fevered rites that bind—and burn—us.

Precision and Paranoia in Motion

Polinger opens with a sequence that functions like a baptism by dread. Underwater, dozen-odd boys descend in slow motion, limbs splayed like drowned marionettes (a visual riff on birth and burial all at once). Water refracts their bodies into ghostly silhouettes, setting an uneasy tone before a single word of dialogue.

Close-ups become instruments of psychological excavation. A bead of water curls along Ben’s eyelash; Jake’s smirk stretches almost imperceptibly into menace. These tight shots transform mundane expressions into evidentiary fragments—proof that every glance carries intent. By contrast, wide-angle surveillance frames capture the camp as an enclosed laboratory. The boys sprawl across locker benches, their clustered bodies resembling test subjects under an unseen gaze.

Perspective shifts feel tactical. At times we adopt Ben’s tunnel vision—his heartbeat echoes in ambient silence, isolating him in the frame. Then the camera climbs to an omniscient height, observing the group’s herd mentality from above, as if Polinger wanted us to recall images of panicked cattle in 19th-century livestock markets.

Editing pulses with ritualistic rhythm. Cuts alternate between water-drill montages—arms slicing through chlorinated haze—and hushed locker-room whispers. In one heartbeat, a playful splash morphs into a jump cut of terrified faces. The disjointed rhythm evokes the fractured psyche of a boy juggling fear and curiosity.

Controlled pacing intensifies emotional surges. Scenes linger long enough for discomfort to bloom; then—wham—a sudden jolt yanks viewers back to reality (or what passes for it at camp).

Widescreen framing accentuates spatial claustrophobia. Tall ceilings and narrow corridors feel conspiratorial, as if the architecture itself conspires against Ben. Polinger uses rule-of-thirds compositions to position Jake at visual apexes—cornered yet commanding—while margins of empty space isolate Eli and Ben, marking them as outliers.

This meticulous choreography of lens, cut and frame transforms a childhood setting into a crucible of power and exclusion. It’s formal play with a purposeful sting.

Hierarchies Beneath the Surface

Polinger constructs the water polo camp as a sealed microcosm, a Petri dish of adolescent rites. Here, communal rituals—drills at dawn, rank conferred by swim caps—mirror the rigid orders of bygone institutions (think military academies of the 19th century, minus the brass). Camp rules are unspoken yet absolute, a closed system where every splash signals allegiance or defiance.

By setting the story in summer 2003, the film captures a moment before pocket computers tracked our every move. Boys wander locker rooms with an illusion of privacy, unaware that social surveillance thrives even without screens. That absence of technology heightens vulnerability; ostracism is physical, immediate and inescapable.

Cliques form like tectonic plates—shifting alliances trigger tremors of anxiety. Insults become incantations: “Soppy” reduces Ben to a stammer; “the plague” transforms Eli into a walking pariah. Hazing rituals (scrubbing ash from hair, circle chants) recall historical witch trials, where communal fear trumped individual reason. And the coach—Joel Edgerton’s Daddy Wags—hovers like a benevolent monarch who’s lost his crown: present but powerless to enforce basic decency.

The plague itself hovers between literal and metaphorical. Is it eczema, or a psychosomatic contagion born of groupthink? Polinger leaves the question dangling, an interpretive gambit that evokes mass panics (see tulip mania or 17th-century plague pamphlets). That ambiguity becomes a lens on exclusionary impulses: fear of difference manifesting as a skin-deep monster.

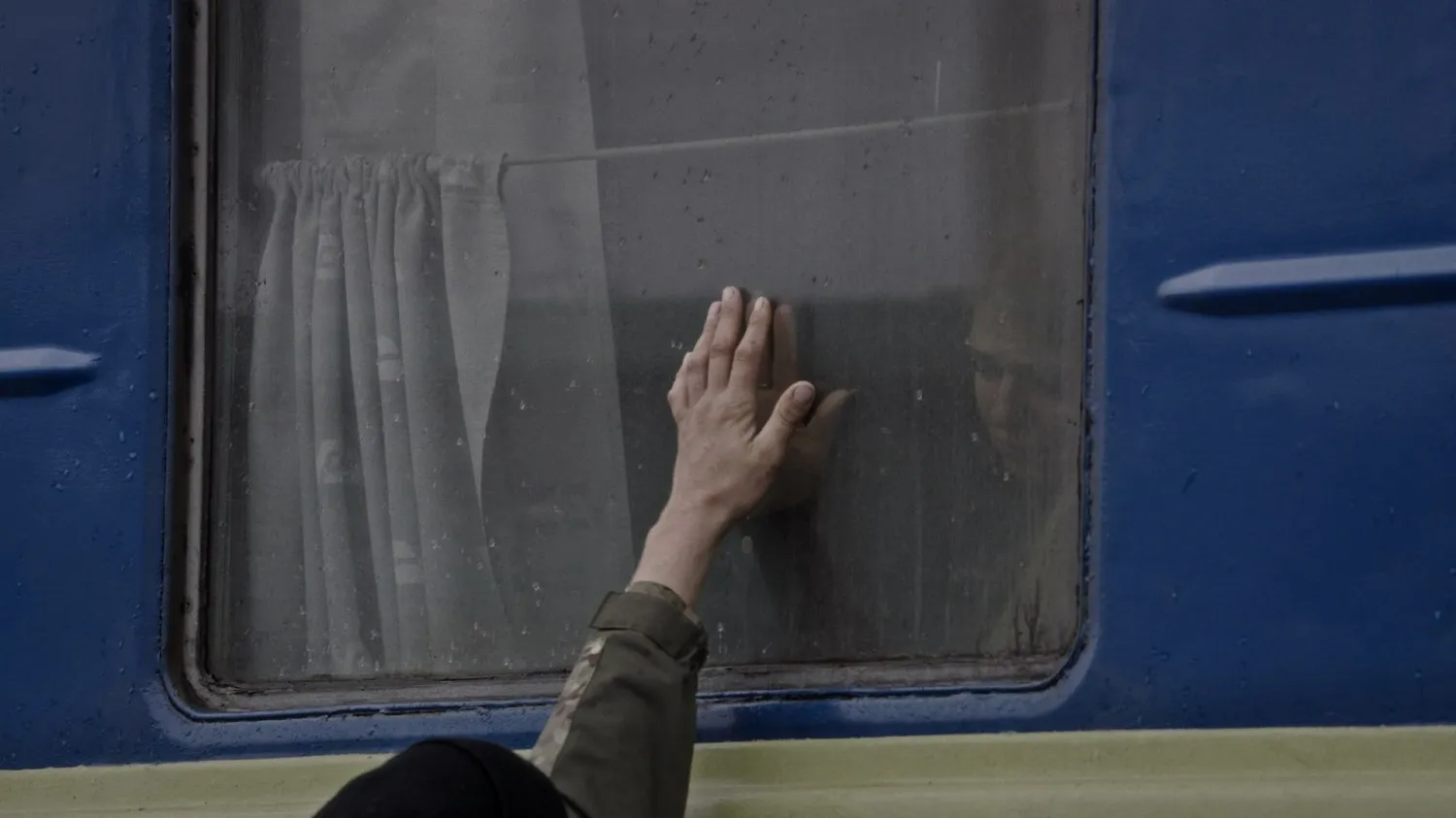

At the center stands Ben’s moral crucible. He weighs self-preservation against empathy, a piston driving narrative tension. His final act—choosing to bond with Eli at the risk of banishment—feels both inevitable and startling, like the moment a river breaks through its levee. Here, coming-of-age becomes a phrase for crossing an ethical Rubicon.

In these dynamics, The Plague suggests that cruelty and compassion are two currents in the same pool. It challenges viewers to confront their own complicity in minor cruelties—those everyday decisions that ripple outward, shaping collective culture.

The Anatomy of Authority and Otherness

Ben arrives as proto-anthropologist, a wide-eyed observer cataloging unwritten camp codes. His posture—shoulders hunched, gaze darting—speaks of both curiosity and latent dread. Early close-ups of his clenched fists (what I’d call “nervous knuckle syndrome”) register his transition from passive newcomer to moral agent. As the story unfolds, his journey arcs from fascination with the group’s rituals to the existential weight of empathy—each broadened glance at Eli etching lines of anxiety across his face.

Jake is charisma incarnate, his grin a percussive instrument that sets the social tempo. Yet that smile curves into menace at the subtlest of cattle prods—an eyebrow raise, a measured pause before a barb. He wields observation like a scout general, mapping vulnerabilities and deploying mockery as tactical strikes. This brand of “surgical social aggression” underpins his dominance, transforming camp camaraderie into calculated performance.

Labeled with the intangible “plague,” Eli stands at camp’s moral frontier (or perhaps its moral nadir). His stillness belies internal dynamism: impromptu dance routines in empty corridors, eerie Gollum impressions, DIY faux-blood experiments. These moments of exuberance puncture the group’s cruel calculus, revealing a form of psychological resilience that defies simple victimhood. His relationship with Ben becomes the film’s true fulcrum—Eli teaches, and in doing so, Ben learns the currency of authenticity.

In Edgerton’s brief cameo, Daddy Wags embodies well-meaning authority that’s inherently outmatched. He dispenses pep talks like generic comfort food—nutritious but forgettable. His presence underscores a key irony: adult oversight is abundant narrative filler yet scant in practical efficacy. As a foil to the boys’ self-governed hierarchy, he illustrates how institutional structures can fail without genuine engagement.

Through these layered performances, The Plague dissects power, othering and the latent potential of unlikely alliances—inviting reflection on how we define both membership and marginalization.

Echoes in Chlorinated Silence

The film’s color palette reads like a desaturated PTSD flashback: grays, steely blues and muted greens wash over every frame. These chilly tones evoke institutional detachment—an aquatic asylum where conformity is enforced by silent currents. In locker rooms, high-contrast shafts of light carve out each boy’s face, turning sweat into a spotlighted confession (or accusation).

Production design leans into minimalism. The pool’s architecture resembles a monastic cloister—endless tile corridors and regimented lanes suggesting spiritual trial more than athletic training. Locker-room props become talismans of exclusion: a blood-smeared towel, a stray water bottle, rash ointment tubes piled like medical evidence (the “plague” dossier in physical form).

Sound operates on a granular level. Dripping faucets and distant sloshes form a constant, aquatic white noise that lulls and unnerves in equal measure. Echoing footsteps—each footfall amplified—remind us that privacy is a myth here. Then, suddenly, a dissonant chord cuts in, a jump-scare cue that repurposes horror tropes for adolescent ritual.

Johan Lenox’s score plays with vocal fragments—distorted shouts that resemble both war cries and playground chants—stitched together with staccato percussion. It’s what I’d dub “sonic hydrophobic,” a sound design that fearfully flirts with silence before unleashing bursts of chaotic energy.

Moments of hushed stillness let us hear the boys’ collective heartbeat in the silence (a daring narrative choice that flirts with overindulgence but ultimately reinforces our empathy). Then the music spikes, mirroring Ben’s moral panic and the group’s herd mentality. In The Plague, every visual and auditory element converges into a visceral shorthand for isolation, conformity and the deep, unsettling waters of group psychology.

Fear’s Quiet Crescendo

Small indignities compound into a creeping dread. A teasing nickname here; a whispered warning there. Each slight crack in Ben’s confidence ripples outward (like microbial contamination in a petri dish), and suddenly the locker room feels like a chamber of whispered verdicts.

We learn to predict the next act of cruelty as instinctively as a chess master foresees a checkmate. That expectancy binds us to Ben’s viewpoint—every glance over his shoulder becomes our own furtive look at an invisible jury.

Yet empathy remains stubbornly intact. We share Ben’s moral vertigo: the pull of acceptance versus the impulse to protect Eli. That tension elicits not only sympathy for the ostracized but also a nagging self-reflection. Who among us hasn’t hesitated before speaking up?

Polinger punctuates oppression with fleeting moments of childlike abandon: a spontaneous poolside race, laughter ricocheting off tiled walls. These interludes feel like oxygen masks deployed mid-flight—brief relief before the next turbulence.

The climactic confrontation doesn’t just resolve the plot; it echoes broader dynamics of tribalism and allyship. It lands with the force of water breaking through a dam, jolting both characters and audience.

Long after the credits, The Plague lingers in the mind’s locker room. It invites us to examine our own silent compliances—and to ask whether small acts of kindness might reshape even the most unforgiving hierarchies.

Polinger’s Alchemy: Rituals of Fear and Belonging

Charlie Polinger’s first feature marries formal audacity with unforced storytelling. He treats his young cast like seasoned thespians—extracting pinpoint authenticity from every flinch and furrowed brow. In Polinger’s lens, children become conduits of atmospheric tension rather than mere supporting players (a bold tactic in debut cinema).

He repurposes horror conventions for a youth drama. Skin-rash imagery flirts with body-horror tropes—think Julia Ducournau’s visceral approach—yet Polinger resists gore for gore’s sake. Instead, he taps into “peer pathology,” where social contagion carries more terror than any physical mutation. Jump scares lurk in everyday moments: a hallway turnaway, a dripping faucet.

Narratively, The Plague channels Lord of the Flies’ tribal undercurrents and Claire Denis’ Beau Travail’s disciplined choreography of bodies in confined spaces. Yet it never reads like pastiche. Polinger synthesizes these influences into what I’d call “ethical horror,” where moral choices ricochet louder than screams.

His original contribution lies in reframing neurodiversity as a catalyst for moral agency. By fusing adolescent rites of passage with unsettling formal play, Polinger invites a cultural reckoning: can cinematic fear serve as empathy’s primer? If so, The Plague stakes a claim on coming-of-age narratives, proving debut directors need not tread lightly to make waves.

Full Credits

Director: Charlie Polinger

Writer: Charlie Polinger

Producers: Lizzie Shapiro, Lucy McKendrick, Steven Schneider, Roy Lee, Derek Dauchy, Joel Edgerton

Executive Producers: Cory Finley, Cullen Conly, James Presson, Rami Yasin

Cast: Joel Edgerton, Everett Blunck, Kayo Martin, Kenny Rasmussen, Lennox Espy, Elliott Heffernan, Lucas Adler, Caden Burris

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): Steven Breckon

Editors: Simon Njoo, Henry Hayes

Composer: Johan Lenox

The Plague premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival on May 16, 2025, in the Un Certain Regard section.

The Review

The Plague

Polinger’s debut harnesses adolescent anxiety into a chilling and thought-provoking journey. The charged performances, immersive sound design and precise visuals coalesce into a potent allegory of exclusion and moral choice. While moments of thematic repetition surface, the film’s sustained tension and ethical depth linger long after the final frame.

PROS

- Immersive atmosphere that turns a familiar setting into uncanny terrain

- Precise cinematography and framing that underscore emotional stakes

- Johan Lenox’s score and layered sound design heighten psychological tension

- Compelling performances from Blunck, Martin and Rasmussen

- Thought-provoking allegory of exclusion and moral agency

CONS

- Occasional thematic repetition undercuts narrative momentum

- Pacing lags in quieter stretches

- Adult figures feel underdeveloped

- Jump-scare beats sometimes telegraphed