There is a particular torment in the collapse of worlds, when the carefully constructed walls between one’s public and private selves are reduced to rubble. FUBAR returns for its second season not with a bang, but with the suffocating quiet of a shared cage.

After the violent revelation of their clandestine lives, the Brunner family and their associates are sealed together in a witness protection home, a purgatory of forced intimacy. Here, they perform a pantomime of domesticity while the specters of their true professions linger in every corner. At the center of this fragile ecosystem stands Luke Brunner, a figure carved from the granite of Cold War certainty, now adrift.

The season’s primary threat is not merely a new antagonist on the world stage; it is an echo from his own past, a debt coming due. A mission materializes, promising an escape from the prison of the home, yet it only drags them deeper into a conflict where the architecture of family proves as volatile as any geopolitical crisis.

The Domestic Panopticon

What is a person when their context is stripped away? The safe house in FUBAR becomes a cruel laboratory for this very question. It is a purgatory where the instruments of death and the artifacts of suburban life share the same space, creating a dissonance that hums with anxious humor. The comedy is not born of wit, but of friction—the grating of two irreconcilable realities against each other.

Killers trained in silent disassembly must now navigate the politics of the last cup of coffee. This forced cohabitation turns every interaction into a performance. The rekindled romance between Luke and Tally is not a private affair but a broadcast, a desperate attempt to re-enact a dead past for a captive audience who can hear every word through paper-thin walls.

In this theater of the absurd, the civilians become the most compelling figures. Jay Baruchel’s Carter is a ghost of a simpler world, his wide-eyed normalcy a constant, silent judgment on the madness he has been absorbed into. But it is Andy Buckley’s Donnie who achieves a kind of tragic grandeur. His profound depression is not a simple emotional state; it is a philosophical position.

Faced with a reality that has become fundamentally nonsensical, he has chosen to withdraw from its terms entirely. His apathy is his armor. His deadpan refusal to participate—the bathrobe that becomes a second skin, the cereal saturated not with milk but with beer—is a quiet rebellion against the void. He is the logical conclusion of a world gone FUBAR: a man who has looked upon the sheer irrationality of his circumstances and decided, quite reasonably, to simply stop trying.

An Old Ghost in a New War

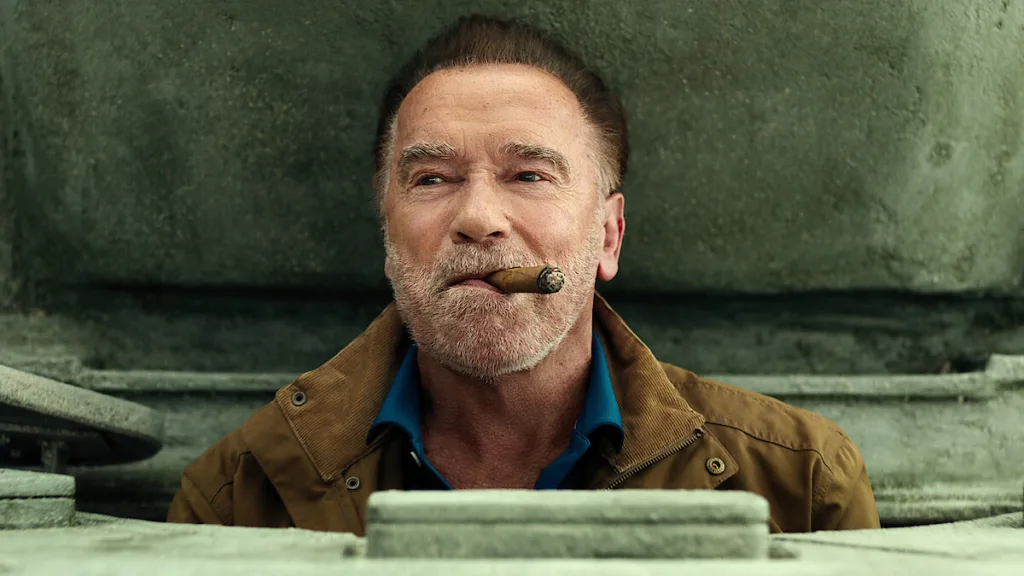

To watch Arnold Schwarzenegger now is to watch a monument contend with its own erosion. He is a relic of an empire of belief, a physical testament to a time when bodies on screen were impervious to consequence. In Luke Brunner, this myth is deliberately fractured. The performance is a knowing dialogue with his own past; the one-liners land less like triumphant declarations and more like echoes from a forgotten language.

The physicality of his combat has changed. It is no longer the effortless ballet of destruction but the grinding, labored work of a man whose body is finally beginning to keep a ledger of its abuses. There is a weight to him now, a weariness that lends an unintended gravity to the proceedings. He is a man built of legend, forced to inhabit a body subject to time.

Into this landscape of personal decay walks Greta Nelson, a ghost from a life he tried to bury. Carrie-Anne Moss plays her not as a simple villain, but as a dark reflection. She is the past incarnate, a woman who never attempted the schizoid separation of identities that has defined and tormented Luke. Their shared moments are steeped in a venomous nostalgia, a longing for a past that was itself a form of destruction.

Yet, the series falters when it attempts to domesticate this profound conflict, reducing their bond to the geometry of a love triangle. The dialogue flattens, the pacing drags. A fascinating exploration of whether one can ever truly escape the person they were is traded for a stilted romantic melodrama. It is a failure of imagination, a retreat from the abyss just as it was beginning to stare back.

Satellites in a Decaying Orbit

The cold war between Luke and his daughter, Emma, thaws into a fragile détente. This is not peace, but a strategic realignment born of shared trauma. Their newfound respect is a functional necessity, the way two soldiers learn to trust each other in a foxhole. For Emma, portrayed with a brittle strength by Monica Barbaro, this is the season of radical disillusionment.

The discovery of her father’s past is not merely a betrayal; it is the final demolition of a foundational myth. She must now construct a self from the rubble, and her independence is less an act of empowerment than a grim acceptance that she is alone. Every choice is a reaction, an attempt to build an identity in the negative space left by her father’s lies.

Surrounding this collapsing familial star are the satellites of the support team. Barry, Roo, and Aldon orbit the central chaos, their camaraderie a poignant counterpoint to the Brunners’ fractured bonds. They provide levity, yet their primary function is to be the stable mass against which the central tragedy can be measured. They are the control group in an experiment of psychic disintegration.

Then there is Theodore Chips, and the series fractures in the most fascinating way. Guy Burnet plays him not as a character but as a singularity of need. He is a man whose interior life has completely breached its container, a walking calamity of unrequited love and misapplied pop-culture catechisms. His menace is inseparable from his patheticness.

He is a black hole of desire, pulling everything toward him with the sheer gravity of his obsession. To be loved by him would be a form of annihilation. In a show about people hiding their true selves, Chips has no self to hide; he is pure, unvarnished, terrifying impulse. He is the grotesque, unhinged heart of the story, a perfect emblem for a world where coherence has been lost.

The Hollow Spectacle

The series presents its violence as a kind of liturgy, a series of rituals meant to signify danger and consequence. Yet the rites feel hollow, the gestures automatic. The firefights are a pantomime of peril, a rote catechism of gunfire enacted in spaces that feel curiously unreal—the generic office, the anonymous warehouse, the bunker that seems recycled from a thousand other forgotten wars.

This is not the visceral terror of genuine conflict; it is the bloodless, weightless violence of a dream, a spectacle whose artifice is constantly showing through the seams. The very fabric of its action feels thin, threatening to tear and reveal the soundstage behind it.

But where the spectacle of violence fails, the theater of the absurd thrives. The show’s true, chaotic pulse is found not in its explosions, but in its humor—a humor born from the friction of souls scraping against each other in confinement. This is the language of survival in a world that has lost all meaning. It is in the grotesque courtship ritual of a spy-tango, a dance of death and desire.

It is in the sudden, unhinged appearance of puppets, a moment where the narrative surrenders to pure farce because logic has already fled. Here, in the carnage-laced carnival of a child’s birthday party, the show finds its most honest expression: a giddy, terrifying acknowledgment that the line between the domestic and the deadly has been erased completely.

A Cacophony of Being

To engage with this season is to witness a system deliberately over-stressed, a narrative engine choked with too many souls. The experience is less a linear journey and more a surrender to a centrifugal force, flinging out subplots and stray desperations in every direction.

It is a story that multiplies itself endlessly, each character’s private sorrow becoming another tributary feeding a sea of generalized chaos. Its great flaw is also its most defining feature: a refusal to commit to a singular form of collapse. Instead, it offers a cacophony. Yet, within this noise, something vital persists.

The show finds its strange, compelling rhythm not in the grand, unfocused architecture of its spy plot, but in the small, resonant frequencies of its characters. It is carried by the gravitational pull of its performers and the grim humor of their shared predicament. One leaves not with the memory of a coherent story, but with the lingering echo of this human noise—a flawed, overstuffed, yet undeniably alive artifact of existential disarray.

FUBAR is an American action-comedy series from creator Nick Santora, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger and Monica Barbaro as a father-daughter CIA duo with hidden identities. Season 2 premiered on June 12, 2025, on Netflix, expanding the cast with additions like Carrie Anne Moss (as former East German spy Greta), Enrico Colantoni, and Guy Burnet. You can stream the full season now on Netflix worldwide.

Full Credits

Directors: Phil Abraham, Jeff T. Thomas

Writers: Nick Santora, Cait Duffy, Michael J. Gutierrez, Lillian L. Wang, Adam Higgs, Scott Sullivan, Penny Cox, Seth Cohen, Amy Pocha

Producers & Executive Producers: Nick Santora, David Ellison, Dana Goldberg, Bill Bost, Adam Higgs, Scott Sullivan, Holly Dale, Phil Abraham, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Matt Thunell, Amy Pocha, Seth Cohen; Producer: Agatha Barnes

Cast: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Monica Barbaro, Milan Carter, Fortune Feimster, Travis Van Winkle, Fabiana Udenio, Jay Baruchel, Aparna Brielle, Scott Thompson, Andy Buckley, Barbara Eve Harris, Gabe Luna, Guy Burnet, Carrie Anne Moss, Enrico Colantoni, Devon Bostick, Adam Pally, Tom Arnold

Director of Photography (Cinematographers): Craig Wrobleski, Colin Hoult, Michael McMurray, Jimmy Lindsey

Editors: J. J. Geiger, Eric Seaburn, Anthony Miller, Sang Han, Christopher Petrus, Ryan J. Knight

Composer: Tony Morales

The Review

FUBAR Season 2

FUBAR’s second season is a study in compelling dissonance. Its spy-fi plot is a hollow spectacle, a series of tired gestures signifying little. Yet within this flimsy framework, a vital, absurdist drama unfolds—a chaotic examination of fractured identity in a domestic purgatory. Carried by the gravity of its performers, the series succeeds not as an action story, but as a darkly humorous and surprisingly resonant portrait of human disintegration. It is a beautiful, overcrowded, and fascinating ruin.

PROS

- A compelling theater of existential absurdity, particularly in its safe house setting.

- Darkly resonant humor born from desperation and character friction.

- Breakout performances that embody the show's chaotic soul (Guy Burnet, Andy Buckley).

CONS

- Hollow, repetitive action sequences lacking weight or consequence.

- An overstuffed, unfocused narrative that dilutes its core thematic potential.

- A stilted, melodramatic romantic subplot that undermines deeper character conflicts.