Warwick Thornton’s “The New Boy” is a haunting Australian fable that grapples with the brutal legacy of colonialism and religious oppression. Set in the 1940s outback, it centers on a nameless Aboriginal orphan boy whose arrival at a remote Catholic monastery sets off a profound spiritual clash.

The defiant child, a conduit to ancient Indigenous traditions, represents an existential dilemma for the well-meaning but culturally imperious nuns who aim to subdue his powerful connection to the land and impose European Christian doctrine. Unfolding with the mythical weight of a campfire tale, this slow-burning work is both an elegy for the subjugation of First Nations peoples and a meditative inquiry into the irreconcilable worldviews forced into violent convergence.

Thornton masterfully conjures the arid majesty of the sun-scorched landscape as the battleground where a reckoning between colonial oppressor and Indigenous spirituality must inevitably transpire, innocence and identity hanging in the balance.

The Orphanage’s Cosmic Interloper

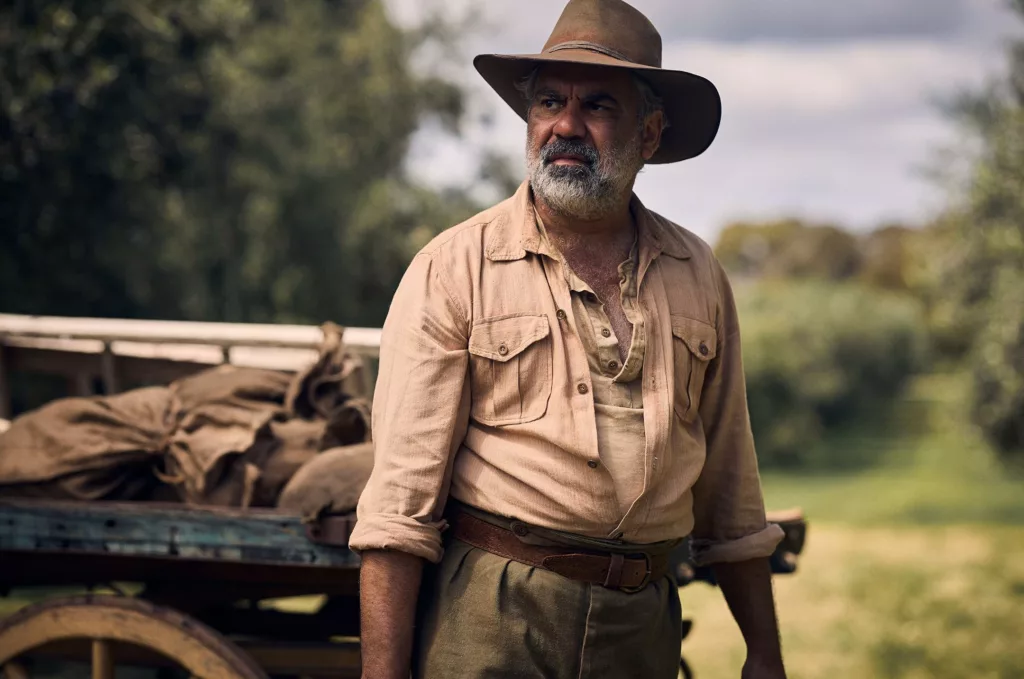

“The New Boy” opens with the ferocious, seemingly supernatural strength of its nameless Aboriginal protagonist – a feral child who brings down a policeman before being captured and deposited at a remote monastery. Here, the rigid Christian dogma of Sister Eileen (Cate Blanchett) governs an orphanage for indigenous boys, part of Australia’s assimilation campaign to instill European values.

Despite her benevolent intentions, Sister Eileen aims to systematically erase the new boy’s ancient spiritual heritage through religious indoctrination and cultural colonization. Yet this mute, shirtless arrival confounds her with his primal mysticism – he can conjure light, seems to possess healing powers, and develops an unsettling fixation on a newly arrived crucifix carving.

As Sister Eileen’s zeal to “save” him grows, the boy’s disquieting, totemic presence evokes the monastery’s Indigenous farmhands’ own suppressed identities. Slowly, the atmosphere gathers with ethnic and metaphysical tension. Is this strange child a messianic figure, a bridge between belief systems – or an untenable affront to the colonial mission’s self-certitude?

Thornton’s Searing Poetic Vision

As writer, director and cinematographer, Warwick Thornton wields total artistic control in sculpting the arid splendor and metaphysical unease of “The New Boy.” His directorial hand is assured yet supple, favoring a meditative pace that lets potent symbolic imagery linger.

Thornton’s camerawork is nothing short of masterful. Sweeping vistas of the baked Australian interior confer an omniscient monumentality, the burnished desert expanses standing as silent witnesses to the cyclic upheaval of settler-Indigenous conflict playing out. These panoramic tableaus are interrupted by tightly formalist compositions – shafts of sculpted light, isolated human figures dwarfed by the land’s vastness.

Such shots magnify the cosmically minuscule yet spiritually profound struggle between the colonized new boy and his usurpers. When Sister Eileen first glimpses her scrappy new charge, she is rendered tiny against the colossal backdrop of a workhouse – a subtle visual rhetorical framing their intrinsic power disparity.

Thornton’s nimble camera also coheres the metaphysical and corporeal realms. Woozy, destabilizing lens flares and preternatural shafts of light limn the new boy in an aura of mysticism. Symbolic elemental forces like fire and snakes take on ethereal portent in Thornton’s calculated yet lyrical framing.

The cyclical, almost trance-like pacing evokes both the vast unhurried rhythms of the landscape and a oneiric state where the intangible intersects with material existence. Aided by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’s droning, ritualistically percussion-driven soundscapes, the filmmaker’s command of tone is extraordinarily immersive and transporting.

Embattled Souls Brought to Vivid Life

At the warring core of “The New Boy” are two spellbinding central performances that give searing emotional immediacy to the film’s weighty cultural convictions.

As the obstinate Sister Eileen, Cate Blanchett embodies the furrow-browed colonial certainty of the Christian settlers with her signature intensity. Striding the monastery in mannered habits and gripping her bible tight, she exudes a paternalistic zeal to stamp out any hint of Indigenous spirituality. Yet Blanchett imbues her with tremulous humanity – her voice wavers with doubt, her rigid posture betrays repressed passions. This is a woman grasping for cosmic meaning while blind to the ancient mystic truths she’s actively suppressing.

On the other side is Aswan Reid’s revelatory, primal turn as the feral New Boy. The young actor’s stillness and transfixing stare conveys a profound interiority, his character a vessel for ancient traditions and a oneness with the land. Reid’s physicality is mesmeric – from his sinuous movements and unsettling mannerisms to the way he repositions his wiry frame with coiled volatility when threatened. His bond with the ornate crucifix carving becomes a riveting spectacle, as if he’s channeling some indecipherable cosmic energy.

The soulful face-off between ruler and ruled, oppressor and subjugated, is electrifying to witness. Blanchett and Reid personify the philosophical gulf separating their characters with both nuance and visceral impact, each staking metaphysical territory in a cultural tug-of-war over spiritual sovereignty and belonging to the land itself.

Reckoning with the Wounds of Cultural Erasure

With poetic grace and visceral intensity, “The New Boy” confronts the psychic and spiritual wounds inflicted by the colonial suppression of Indigenous cultures. Warwick Thornton’s fable operates on dueling temporal planes – grounded in the specific historical context of 1940s Australia’s racist assimilation policies, yet also tapping into timeless, mythic dimensions of subjugation and resistance.

On one level, the film is an unflinching portrayal of how Christian dogma was weaponized as a tool of ethnic cleansing against Aboriginal peoples. The well-meaning Sister Eileen is a cog in this insidious machinery, her seemingly benevolent goal to “civilize” and convert the nameless new boy a de facto campaign of cultural erasure. Her attempts to systemically extinguish his connection to ancient animistic traditions is rendered with haunting poignancy.

Yet Thornton imbues the new boy with cosmically symbolic significance too. He seems less an individual than an embodied conduit for the profound Indigenous spirituality and mysticism that settler colonialism sought to eradicate and replace with European belief systems. His uncanny abilities to conjure light, commune with nature, and perceive unseen mystical realms position him as the defiant, messianic embodiment of a pre-colonial heritage.

The searing conflict between these polarized worldviews unfolds with raw existential urgency. As the new boy forges an elemental, shamanistic bond with the carved crucifix icon, spiritual lines become blurred and seemingly irreconcilable dogmas enter a cosmic convergence. Is the boy’s ancestral power and oneness with the land irrevocably incompatible with Christianity’s creeds? Or could these clashing metaphysical spheres coexist if the colonizers’ suppressive myopia didn’t render compromise impossible?

Thornton’s haunting visuals catalyze these esoteric concepts into visceral, unsettling symbolic resonance. The cyclical rhythms of nature and the landscape’s boundless primordial splendor imbue the new boy with sacred cosmic dimensions, while shadowed monastery interiors and dogmatic rituals represent the structures of oppressive order. Throughout, an unshakable sense of loss and desecration lingers – of an ancient world fractured and subsumed.

Ultimately, “The New Boy” is a profound lament for the ethnic and spiritual survivors of colonialism’s brutality. In channeling the perspective of the oppressed through his mythic storytelling, Thornton reckons with cultural genocide’s immeasurable toll while leaving a glimmer of hope that the essence of Indigenous traditions may prove too deeply rooted in the land to ever be fully extinguished.

Sublime Visions, Fragmented Storytelling

For all its sublime visuals and thematic ambition, “The New Boy” is not a perfect film. Warwick Thornton’s poetic exploration of colonialism’s spiritual violence towards Indigenous peoples occasionally stumbles in fully cohering its narrative and character arcs.

Where the movie unquestionably soars is in Thornton’s breathtaking command of the cinematic frame as writer, director, and cinematographer. His captures of the sun-blasted Australian outback infinity are gifts of searing, transporting beauty. The compositions marry the mythic and tangible, the corporeal and metaphysical, with haunting virtuosity – whether it’s the new boy’s tiny figure dwarfed against monumental landscapes or shafts of ethereal light seeming to emanate from his very being.

Matched with Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’s droning, ritualistically percussion-driven soundscapes, Thornton achieves an intoxicating, trance-like visionary splendor that immerses viewers in a cosmic reverie. Stark formalist framing continuously reconnects the metaphysical abstractions to tactile material existence.

The central performances of Cate Blanchett and young Aswan Reid as the transfixing new boy are nothing short of spellbinding as well. Blanchett’s tremulous vocal inflections and haunted physicality enrich her character’s spiritual aridity, while Reid’s preternatural stillness and soulful attunement to nature conjure profound reservoirs of ancient mystic wisdom.

Where the film stumbles is in lacking a consistent narrative cohesion to ground its more elliptical metaphysical poeticism. Sister Eileen’s motivations and psychological unraveling grow increasingly muddied, her character’s shift into drunken mania feeling like an overcooked narrative detour. And while the new boy’s cosmic dimensions are evocatively etched, his grounding as an individual gets hazier as the story progresses into pure allegory.

These flaws likely stem from the challenge of balancing Thornton’s distinct avant-garde ambitions with more conventional storytelling obligations. But if “The New Boy” doesn’t fully harmonize its goals, the sheer filmmaking mastery and thematic urgency of its most rapturous sequences render it an overwhelming artistic achievement nonetheless.

Transcendent Cinematic Poetry

In the end, “The New Boy” stands as a mesmerizing and deeply affecting work of transcendent cinematic poetry. While its storytelling may lose some coherence in reaching ambitious thematic heights, Warwick Thornton’s searing visuals and the existential power of his parable render it an overwhelming artistic success.

This is a film that imprints on the soul. Thornton’s evocative imagery of the mystical colliding with the institutional, the colonizer’s rigid dogma imposing on the primal oneness with nature, achieves a spellbinding visual lyricism. His exploration of spirituality, ethnic identity, and the violence of cultural erasure elevates archetypal ideas into urgent, emotionally resonant drama.

While continuing the auteur’s study of Aboriginal marginalization that defined masterworks like “Samson and Delilah,” “The New Boy” scales even more metaphysical and poetic heights. Filtered through Thornton’s singular directorial lens, the battleground between First Nations mysticism and European religious colonialism becomes a profound meditation on clashing cosmologies and the suppressed ancestral bonds that can never be fully severed.

With its rapturous visuals and performances that sear into the psyche, this deeply felt lament for a desecrated spiritual heritage marks an impressive evolutionary leap for one of contemporary cinema’s most vital, uncompromising voices. A major cross-cultural artistic achievement has been unleashed unto the world.

The Review

The New Boy

While its narrative momentum occasionally lags, "The New Boy" is a stunningly crafted, thematically rich meditation on the spiritual violence and cultural erasure inflicted on Indigenous peoples. Warwick Thornton's poetic cinematic voice reaches rapturous heights in this visceral Australian fable, which meshes the mythic with the tangible in transporting visuals. Anchored by Cate Blanchett's haunting performance as a well-meaning nun blinkered by colonial dogma, the film reckons with the subjugation of Aboriginal mysticism and ancient bonds to the land. Yet it's the preternatural presence of young Aswan Reid as the mesmeric title character that most potently channels the generational anguish and mystical wonder at the story's core. A major artistic statement grappling with ethnospiritual identity, cultural genocide, and the eternal resonance of ancestral traditions, "The New Boy" cements Thornton's status as an essential voice in Indigenous cinema. For its thematic ambition and moments of transcendent cinematic artistry, it admittedly warrants:

PROS

- Stunning cinematography and visuals that poetically capture the Australian outback

- Powerful performances, especially from Cate Blanchett and young Aswan Reid

- Explores rich, weighty themes of colonialism, cultural erasure, and spiritual oppression

- Haunting and immersive atmosphere with a mythic, fable-like quality

- Insightful commentary on the clash between Indigenous spirituality and Christian dogma

- Exemplary direction and singular artistic vision from Warwick Thornton

CONS

- Narrative can feel unfocused and muddled at times, losing cohesion

- Sister Eileen's psychological unraveling arc feels overcooked

- Metaphysical poeticism occasionally comes at the expense of grounded storytelling

- Deeper exploration of Indigenous beliefs/practices could have enriched subtext

- Somewhat uneven pacing, with some portions dragging