When I first heard about Trapezium, I was skeptical and curious. Adapted from a novel by Kazumi Takayama, a former member of the idol juggernaut Nogizaka46, and directed by Masahiro Shinohara with CloverWorks animation, the pedigree alone piqued my interest. After all, Takayama’s insider perspective on the idol world offered authenticity, if not vulnerability, while CloverWorks’ reputation for producing visually stunning works (Spy x Family, Bocchi the Rock!) hinted at a polished spectacle.

Nonetheless, Trapezium is not what it seems at first glance. It presents itself as a coming-of-age story — the kind of breezy, pastel-tinged animation where friendships are formed, and dreams come true — but what lies beneath is a darker, more frightening investigation of ambition, deception, and the cost of stardom.

Expectations, I’ve discovered, can be both a prison and a prism. When I approached Trapezium, I expected something formulaic: catchy J-Pop interludes, sugary moments of friendship, and the unavoidable triumph of dreams over obstacles. The narrative, however, feels practically allergic to the traditions of the idol anime genre.

This is not the bright optimism of Love Live!, nor the close companionship of Bocchi the Rock! Instead, Trapezium dares to muddy the waters by introducing a protagonist whose goals lead her to deceive people around her under the appearance of friendship. It’s an unusual entry in a genre that thrives on the illusion of peace, and although this subversion is intriguing, it also feels curiously incomplete, as if the film is unsure how far it’s ready to go in critiquing idol culture’s machinery.

The Gravity Beneath the Glitter

When ambition is stripped of pretense and exposed for its ugly paradoxes, it has a seductive and unnerving allure. In Trapezium, Yu Azuma’s well-planned plot to form an idol group initially feels like an act of sheer, almost American grit – a bold, unashamed pursuit of a dream. She’s a strategist and a tactician; she scouts her “targets” with the precision of a chess master, moving from school to school to create her ideal constellation.

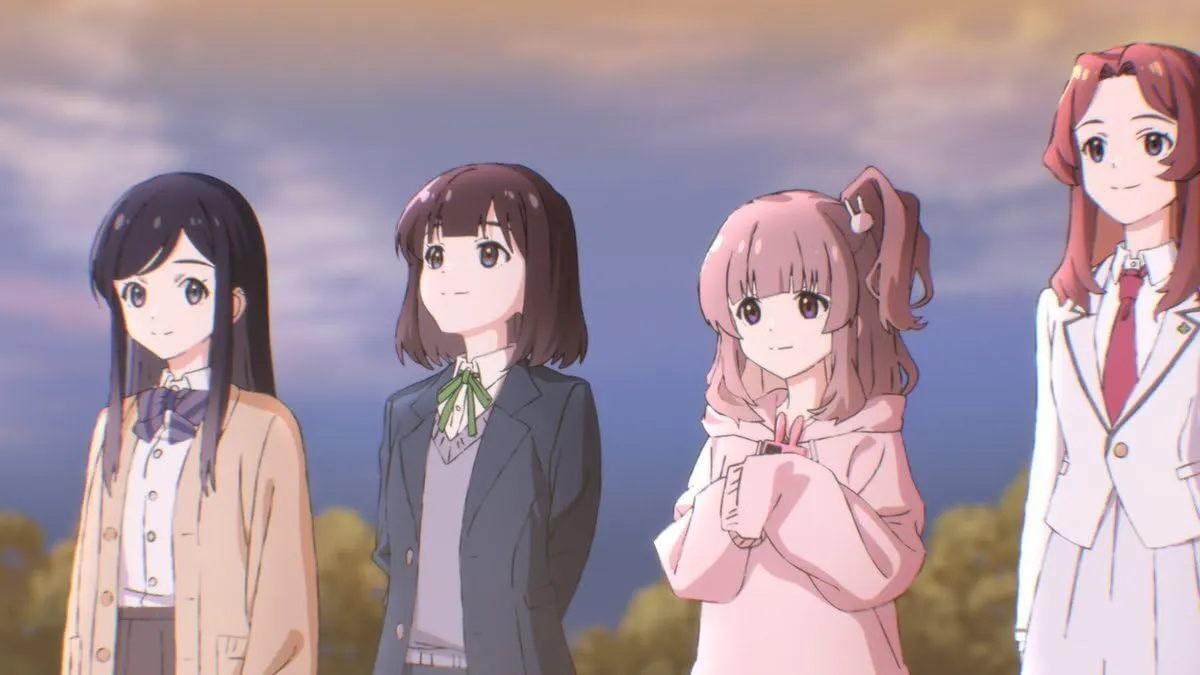

There’s Ranko, the confident and wealthy athlete from the south; Kurumi, the robotics genius from the west; and Mika, the selfless volunteer from the north. Each lady is picked for the archetypes they represent and the shine they can bring to Yu’s idea of stardom, not for who they are as people.

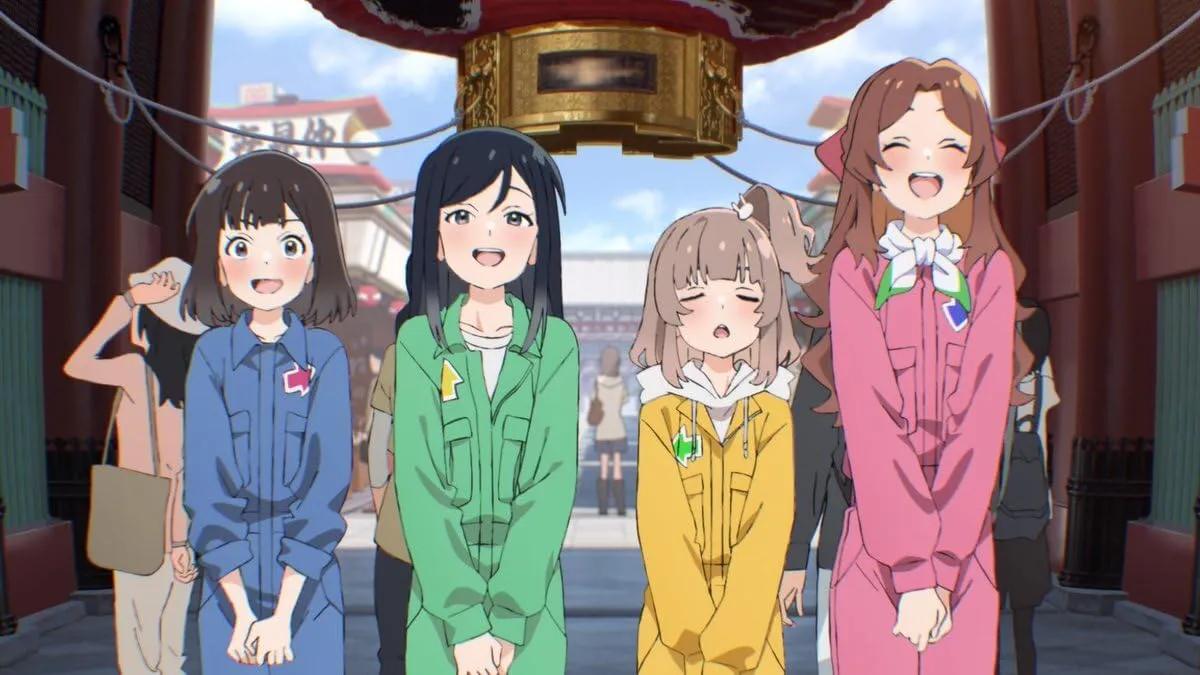

The narrative offers moments of sweetness as the group grows to prominence, the kind of transient, surface-level friendship that idol stories frequently play on. The girls appear for glossy commercial images, perform their polished routines, and share the spotlight.

Nonetheless, these situations have an odd hollowness, a feeling of deception that almost feels deliberate. Did You ever really see these girls as pals? I found myself wondering. Or were they always just pieces on her board, replaceable components of a plan to make her dream a reality?

Cracks begin to show, as they must. Kurumi’s quiet attitude crumbles under public scrutiny, while Mika’s charity clashes with Yu’s cold, practical approach to their volunteer work. The idol industry’s pressures, such as compulsive perfectionism and a smothering demand for purity, cause tensions that feel both intensely personal and painfully societal.

I considered the real-world idol scandals I’d heard about, in which young women’s lives are dissected and discarded for the sake of a fabricated image. Trapezium touches on the same discomfort but never completely explores it.

Yu’s unraveling is both inevitable and unsatisfactory. The climax, which should be a reckoning, feels strangely muted as if the film is afraid to directly address its protagonist’s manipulations. The pacing is off here, racing through the ramifications in a way that frustrates me — not because I wanted Yu to suffer, but because I wanted the film to struggle more honestly with the consequences of her choices. But perhaps that is my prejudice showing: my desire for stories to provide moral clarity, even when life rarely does.

Yu Azuma: A Star Born in Shadows

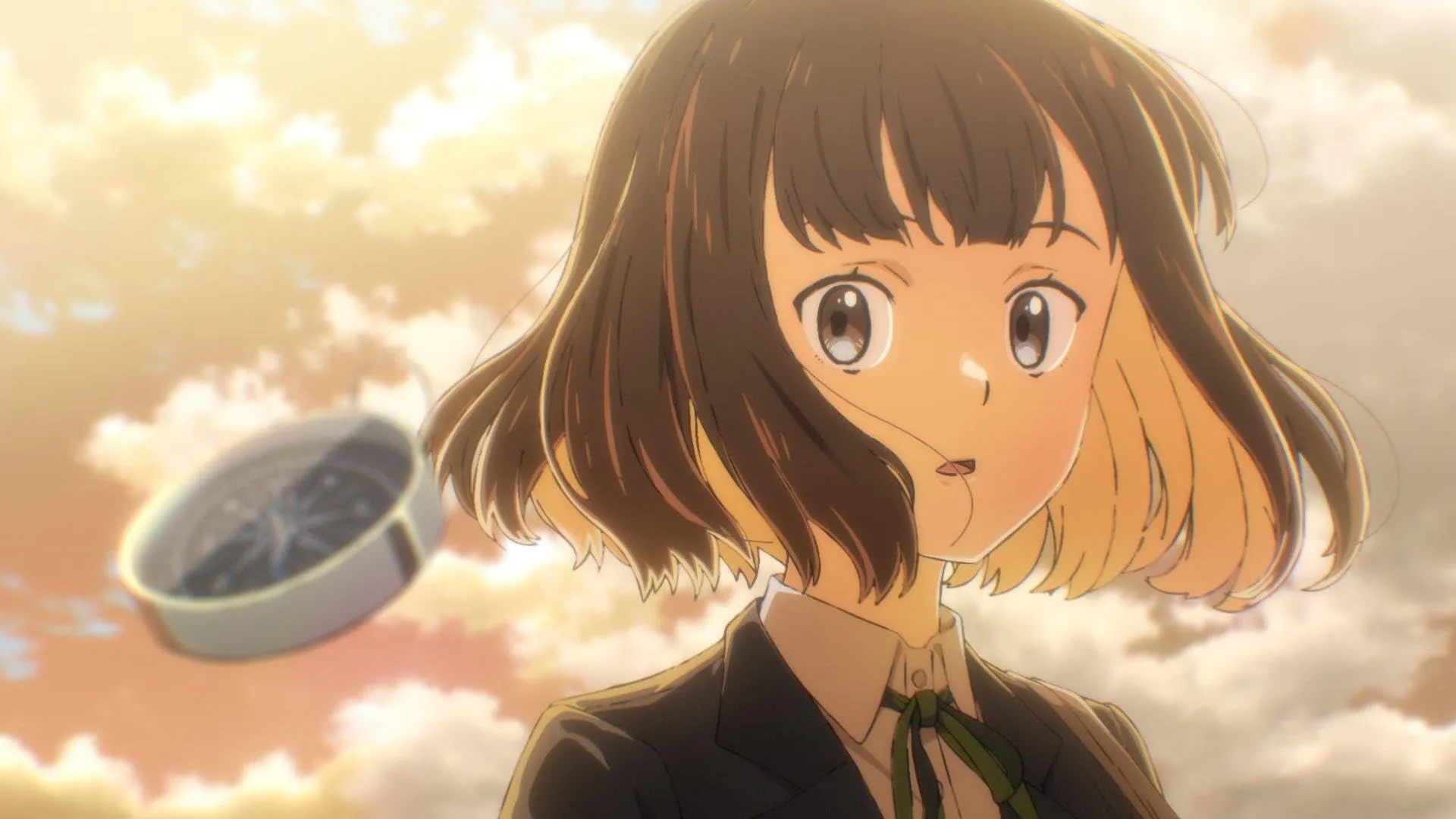

Yu Azuma is not the kind of protagonist you want to root for. Regardless, I couldn’t take my gaze away from her. Her ambition has an oddly seductive quality, this naked, unfiltered desire to become an idol at all costs. She tackles her dream with the precision of a scientist dissecting a creature, treating her prospective bandmates like variables in an equation.

Ranko’s elegance, Kurumi’s viral renown, Mika’s intrinsic decency – Yu doesn’t initially recognize them as people. She arranges them as assets, puzzle pieces to form the ideal image of success. However, beneath her calculating veneer, a vulnerability flickers just enough to confound your feelings for her.

I found myself torn between adoration and discomfort. Yu’s unwavering determination has a weird, almost alluring appeal, a kind of honesty in her willingness to defy the unspoken norms of friendship in pursuit of her dream. I couldn’t help but recall my moments of ambition when I twisted circumstances — or people — to meet my objectives.

But Yu goes much further, using manipulation as a shield and a weapon. Watching her, I wondered where the line was between ambition and selfishness. What’s the difference between resolve and cruelty? And, perhaps more troublingly, why did I find myself pulling for her despite her lies and schemes?

Despite its willingness to show Yu’s flaws, the film is unwilling to thoroughly probe them. Her manipulative behavior — the lies, the subtle emotional compulsion — goes completely unpunished as if the narrative is complicit in defending her. Is the film trying to portray Yu as a sad antihero or a misunderstood dreamer? It’s ambiguous, which left me disappointed. There’s room for a more in-depth examination of her psychology in Trapezium. Still, it holds back, leaving Yu’s moral path frustratingly undercooked.

In some ways, Yu reminded me of Rei Hino from Sailor Moon or possibly Nanami Kiryuu from Revolutionary Girl Utena – characters whose harsh edges conceal deeper fears. However, whereas those characters deal with their conflicts in complex and careful ways, Yu’s journey feels incomplete. She is fascinating but slips through the narrative cracks in ways that feel less purposeful and more like squandered possibilities.

And yet, perhaps that is the goal. Perhaps Yu is meant to remain unknown, like a star that shines too brightly to be seen properly. Perhaps I’m giving the film too much credit, creating depth where it lacks. Either way, Yu stuck with me long after the credits had rolled, less as a person and more as a question—one that I’m not sure I can answer.

The Quiet Poetry of the Mundane

Trapezium’s appearance is immensely comforting—not spectacular or revolutionary, but familiar in an almost tactile way. CloverWorks, famed for their ability to switch between the exuberant (Spy x Family) and the mournful (Rascal Does Not Dream of Bunny Girl Senpai), opts for a restrained, almost understated design.

The animation lacks the kaleidoscopic intensity that one would anticipate from an idol film. Instead, it lingers in the mundane: the warm glow of afternoon sunlight flowing through a classroom window, the personal mess of Yu’s bedroom, or the muted tones of a robotics lab. It’s a world that feels lived-in, grounded in the every day, and this subtle attention to detail makes the film’s portrayal of teenage ambition feel weirdly timeless.

The character designs, too, contribute to this authenticity. Each girl’s appearance is a reflection of her personality: Ranko’s polish, Kurumi’s modest practicality, and Mika’s warmth beaming from her large pink sweaters. And then there’s Yu, who feels more difficult to pin down; her design is almost too tidy and too composed as if she’s built herself as meticulously as she does her blueprints. At times, I found myself staring at her expressionless face, wondering if I was witnessing her real self or just another layer of act.

The way the understated visuals softly amplify the story’s themes, however, impressed me the most. The girls’ dreams are put in a melancholy light due to the repeated imagery of stars, notably the Trapezium Cluster. The stars are lovely, but they are also far away and impenetrable. Perhaps the film’s greatest triumph is how it employs its visuals to remind us of the fragility of ambition and the tenuousness of connection. It’s a world that doesn’t need to yell to make itself heard, though I’ve wondered if it speaks too gently for its own benefit.

The Silence Between the Notes

Trapezium is an unusually calm film for one set in the world of idols. The music, traditionally the lifeblood of the idol genre, feels almost inconsequential here, like a faint pulse rather than a driving force. Whereas series like Love Live! or Bocchi the Rock!

Incorporating songs into the emotional fabric of their characters’ journeys, Trapezium is content to let music hang in the background, a distant echo of what the story may have become. This absence is noticeable, almost confusing as if the film were purposefully rejecting the joyous, uplifting tone typical of its genre.

There are a few songs: a shiny premiere tune that feels like a manufactured smile, a theme song that fades away as swiftly as it appears, and a concluding piece composed by the protagonists themselves. The latter is maybe the most moving, not because it is particularly memorable, but because it feels like a rare moment of honesty in a story generally full of deceit. But even this song, meant to represent development and unity, feels weirdly hollow – possibly a reflection of the group’s fragmented journey.

Maybe that is the point. Perhaps the film’s muted approach to music is its way of critiquing idol culture’s superficiality. Perhaps it’s simply a squandered chance, a silence that reflects absence rather than intention. I am still not sure.

The Bright Lights and Dark Shadows of Fame

Trapezium’s portrayal of the idol industry has an unsettling honesty, a kind of silent condemnation that feels more personal than dramatic. Yu Azuma and her group’s pressures and exploitation are never sensationalized; instead, they are weaved into the fabric of the story in ways that feel uncomfortably normal.

The underlying rules are straightforward: your life is no longer your own. Mika must end her romance since idols uphold the illusion of unreachable purity. Kurumi, who was already weak, began to break under relentless observation. Even Ranko, who appears composed, is a cog in this glittering machine, trained to smile and shine no matter the cost.

As someone who has followed the real-life crises in the idol world — coerced apologies, public shaming, and the continuous monetization of youth — I couldn’t help but feel a sense of recognition. Trapezium does not delve as deeply into this critique as I would have liked. Still, the shadows are present, lingering around the borders of its pastel palette. There is an implied critique of the industry’s superficiality, appearance fixation, and neatly managed personalities. However, the film refrains from destroying these systems, possibly restrained by its desire to entertain.

Underneath this industry critique is a more general examination of adolescence and ambition. Yu’s path is, in many ways, a story of self-discovery, albeit fundamentally flawed and frequently unpleasant. Her unwavering desire to become an idol blinds her to the needs and desires of others around her, transforming friendship into a means to an end. Isn’t that, in some ways, the core of growing up? Adolescence is messy, greedy, and full of mistakes we don’t realize we made until later. I caught between annoyance and empathy for Yu, wondering how I would have behaved in her place.

It’s impossible to overlook Kazumi Takayama’s influence on this story. As a former idol, she writes with an unwavering gaze, balancing insider knowledge with a reflecting distance. I wonder if Yu answers her questions about ambition, friendship, and the cost of pursuing a dream. If that’s the case, the story is about coping with uncertainty rather than finding answers.

A Star That Flickers, Not Shines

Watching Trapezium feels like holding something fragile – a story between brilliant and incomplete. The film is a character study of Yu Azuma, whose ambition burns so brightly that it consumes everything around her, even her humanity.

Her connections are transactional, and her methods are cutthroat, but her vulnerability evokes an uneasy familiarity. The narrative’s examination of the idol industry flirts with critique but never fully commits, as if afraid to bite the hand that feeds it.

CloverWorks creates a grounded, gloomy world in which even the stars feel distant, their light dulled by the weight of reality. The music is modest and understated, reflecting this discipline. Still, its absence creates a void in a genre that thrives on melody. While the themes of adolescence, ambition, and exploitation are powerful, they remain half-formed, like a notion the film is too shy to communicate properly.

Who is Trapezium intended for? Perhaps for individuals who enjoy broken characters and muted stories or idol fans interested in the genre’s darker, quieter aspects. Despite its ambition, the film’s impact feels like a whisper rather than a yell — lingering, yes, but too mild to resonate.

The Review

Trapezium

Trapezium is a smart but imperfect investigation of ambition and the idol industry, offering moments of quiet brilliance that is all too often overshadowed by its hesitations. While the film's grounded visuals and morally complex protagonist encourage reflection, it fails to adequately develop its themes or critique the systems it depicts. It's a captivating character study that comes just short of fully penetrating, leaving viewers with questions that feel like missed chances rather than deliberate ambiguities. For those seeking a satirical perspective on the idol genre, Trapezium is worth viewing. Still, it won't be in the spotlight for long.

PROS

- Morally complex protagonist.

- Subtle critique of the idol industry.

- Grounded, detailed visuals.

CONS

- Underdeveloped themes and resolution.

- Pacing issues, especially in the climax.

- Sparse and unmemorable music.

- Ambiguity that feels incomplete.

- Limited emotional impact.