A woman immolates herself in a silent glade—flames licking ancient pines as unseen figures watch, half‑hidden by shadow. It’s an opening so arresting it brands itself onto the mind (and yes, I double‑checked that no stunt person was harmed).

Judith, a no‑nonsense Berlin paramedic, inherits her estranged father’s rural estate in Lower Austria. She and her photographer husband, Ryan, arrive expecting a quick sale. Instead, they tumble into a labyrinth of ritual and memory, coaxed by a cadre of overwhelmingly polite—and overwhelmingly female—villagers.

The setting wears two faces: sun‑dappled woodland trails give way to looming crosses, deer skulls hanging like mute sentinels. Prochaska summons the mood of 1970s cult horror, echoes of Rosemary’s Baby and Wicker Man reborn in damp mountain air.

This marks Andreas Prochaska’s cinematic comeback after eleven years (his last feature, The Dark Valley, felt like a farewell to the Western). He places Julia Franz Richter at the story’s churning center—her Judith both healer and haunted, every controlled breath hinting at buried wounds.

Isolation fractures time; flashbacks creep into the present. We sense not only personal trauma but a broader commentary on communal coercion—how societies demand sacrifice in the name of tradition or duty. Motherhood becomes both promise and prison, a theme as old as recorded history (witness the burning of “witches” in nearby valleys centuries ago).

The stakes are simple: escape or assimilation. And that question reverberates far beyond this one cursed village.

Temporal Tensions and Communal Rituals

In its first act, Welcome Home Baby establishes Judith as the archetypal modern professional—Berlin paramedic by day, dutiful partner by night—only to yank her into an antiquated world. She arrives with Ryan (whose camera lens frames everything like an ethnographer on safari), expecting a tidy transaction.

Instead, the film stages a collision of urban efficiency and folkloric inertia: sealed wounds meet sealed-off bylaws, and the viewer senses a deeper commentary on how globalized rationality often clashes with localized tradition. (Small towns are rarely this polite.)

Act II slips us into dream‑logic: hive‑swarming nightmares, blackouts that fragment time, and an insistent chorus of village women urging Judith to don her late father’s mantle. The screenplay stages “role inheritance” as a social edict—women here are midwives of community destiny, and Judith’s child‑free choice becomes a symbolic affront. Bee stings mutate into collective consciousness; deer carcasses litter roadsides like pagan tutelaries. One can’t help but recall the witch trials of early modern Europe, where female autonomy was routinely recast as heresy.

Clues to Judith’s buried past arrive as visual riddles: a jagged scar, scratched‑out family portraits, patterns of erasure that mirror the screenplay’s own half‑told history. These motifs accrue meaning (or menace) faster than rational explanations, inviting us to trust feeling over fact—a bold scriptcraft decision I’ll call “emotive ontology.”

Ryan’s allegiance fractures in parallel to Judith’s psyche. His camera captures truth yet cannot decode it—perhaps a cheeky dig at our own era of endless documentation but scarce comprehension.

By the third act, Prochaska unleashes a ritualized climax where camp excess flirts with subdued dread. A no‑holds‑barred showdown that feels both cathartic and terrifyingly open‑ended. Does Judith emerge reborn—or merely recast as another node in the village network?

The screenplay’s greatest feat lies in its tonal oscillation: it is at once spare and hallucinatory. Yet there are moments when logic buckles under the weight of its own mythologizing. Still, the balance between exposition and visual poetry (more showing, less telling) earns it a place among the most intellectually adventurous horrors of recent memory.

Architects of Unease: Directorial Grammar

Prochaska opens with a literal blaze—an immolation so immediate it demands your attention (and yes, this is a horror movie, not a pyrotechnics demo). From that initial shock, he applies what I’d call a “tension dialectic”: long pauses that feel like withheld breaths, punctuated by sudden auditory strikes. Silence here isn’t absence but a loaded weapon—each creak of floorboard or rustle of leaves becomes a potential threat, much like the quiet before political upheaval in history’s darker chapters.

Visually, he favors off‑kilter angles that leave Judith dwarfed in her environment. Pools of light carve her figure out of darkness, suggesting both sanctuary and spotlight interrogation. Red flags lining the main road recall more than festive decoration; they evoke authoritarian iconography—an unwelcome welcome mat. Deer carcasses appear not as gore for gore’s sake but as totemic relics (a sly nod to pagan sacrificial rites and the ecological fallout of human intrusion).

Hartusch’s editing is alternately languid and jarring. A lingering two‑shot in the dimly lit parlor might stretch ten seconds too long—only to snap into a blackout blackout jump scare that rattles the nerves. These temporal jumps mirror the disorientation of trauma survivors, whose memories arrive in staccato bursts rather than neat narrative arcs.

Production design operates as silent exposition: scratched‑out family photos become hieroglyphs of forgotten sins; rusty keys hint at locked histories; devilish paintings lurk like folklore made flesh. Outside, the village wears its menace lightly—flower boxes and whitewashed walls that, upon closer look, bear the faintest cracks. It’s as if Prochaska wants us to remember that paradise often masks its teeth.

Embodied Anxieties: Character Alchemy

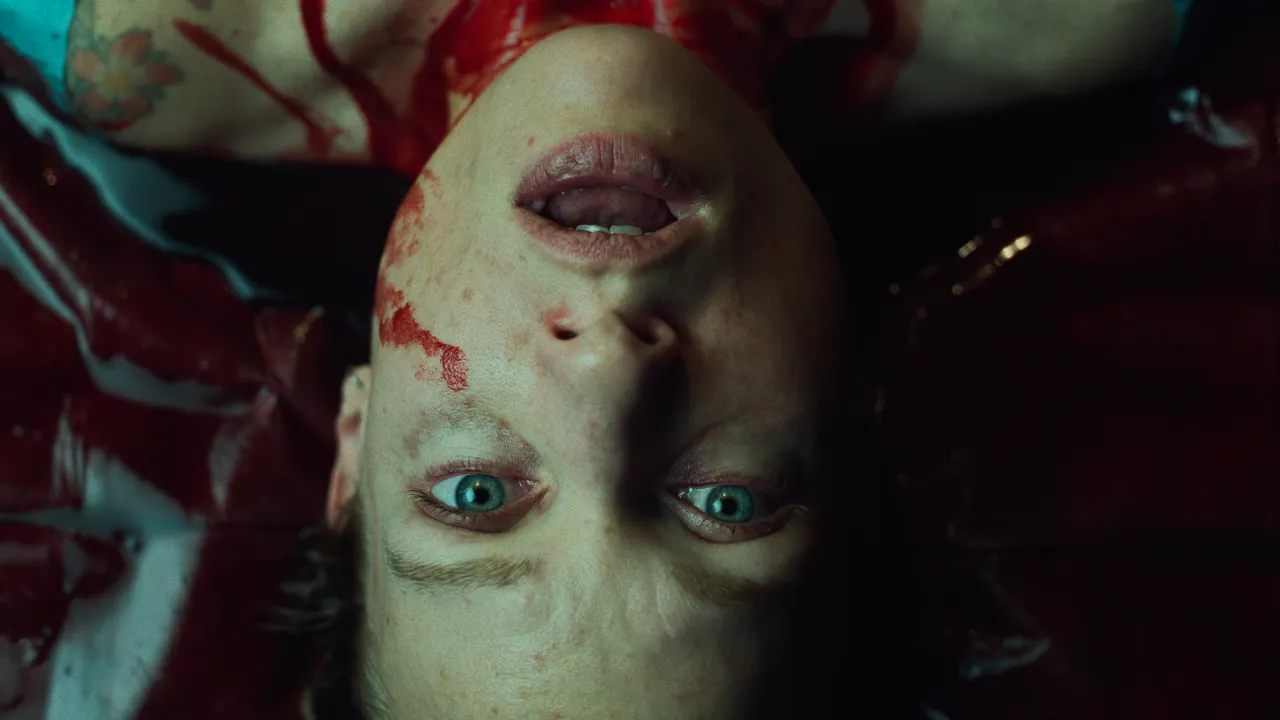

Julia Franz Richter transforms from a composed Berlin paramedic into a vessel of unraveling dread. In the film’s visceral birth and fire sequences, her physicality becomes a battleground—every muscle tensed, every exhalation a silent scream. (She makes “I’m fine” look like a declaration of war.) Her micro‑expressions—an almost imperceptible curl of the lip, a flicker of the eyes—map the terrain of doubt and defiance, charting a psychological descent that feels both intimate and mythic.

Reinout Scholten van Aschat’s Ryan starts as the dutiful spouse with an ethnographer’s curiosity, camera ever at the ready. Gradually, he morphs into a stand‑in for our own complicity: he watches, records, but seldom intervenes. His shifting loyalties—caught between love and allegiance to the village’s invisible code—mirror societal moments when observers become collaborators (think silent bystanders in historical witch hunts). At times, I wondered if his role was a sly commentary on the “male gaze” gone haywire.

Gerti Drassl’s Aunt Paula is quietly electrifying—a matriarch whose benign smile chills more than any overt threat. As leader of the village’s women’s circle, she embodies the paradox of nurturing cruelty. Each ritual she orchestrates (potluck dinners with severed deer hearts, anyone?) reveals sisterhood as a site of power play, where hospitality can quickly tip into enforced assimilation. Drassl licenses us to admire and recoil in equal measure.

Minor roles echo larger themes. The cheery real‑estate agent feels like a satirical footnote—her perfunctory cheer a stand‑in for capitalist indifference. Meanwhile, the male villagers lurk on the periphery, spectral and powerless, underscoring an inversion of patriarchal norms. Together, these performances coalesce into a living mosaic of communal ritual and individual resistance.

Elements of Dread: Visual and Aural Architecture

Carmen Triechl wields her camera like an archaeological tool—excavating layers of dread in every frame. The color palette swings between blood‑red interiors (an implicit nod to propaganda aesthetics) and frigid blues that feel clinically detached. Sunlight seeps through frost‑rimmed windows one moment, then collapses into obsidian black the next. Tilted angles abound, isolating Judith in geometries of terror—though occasionally the effect feels like tensioncraft run amok.

Production design turns the family home into a palimpsest of secrets. Peeling wallpaper reveals ancient stains. Rusted medical instruments hang like relics in a dusty shrine. Photographic prints marred by claw‑edged scratches serve as mute testimony to erased histories. Outside, crucifixes loom above chalets festooned with red flags (a curious echo of mid‑century rallies), while roadside shrines promise salvation or sacrifice.

Sound functions as a fifth character. Rustling leaves morph into whispered incantations. A distant church bell tolls in metrically irregular beats—soundcartography that unsettles on a pre‑linguistic level. The score opts for droning minimalism, punctuated by sudden crescendos that hit like ritual horns. Silence is weaponized: long absences of sound sharpen the next jolt. One might imagine this approach influencing a new wave of German‑language horror to regard quiet as active menace.

Special effects ground the supernatural in grim reality. The birth scene relies on practical gore—flesh and fluid captured in unforgiving detail—while digital flames in the opening prologue occasionally lack tactile weight. The scar prosthetic on Judith’s chest is so seamlessly applied it reads as a metaphysical landmark. Fog drifts through forest clearings like a hallucinogenic veil, hinting at collective trance states.

There’s a paradox here: technical precision that occasionally veers into over‑styling, yet overall these crafts coalesce into an immersive net of uncanny atmospherics. One can imagine its influence rippling through folk‑horror revivals, inspiring directors to treat every design choice as a cipher.

Roots of Ritual and Rebellion

Motherhood here is weaponized (or “womb-witched,” if you will)—a fixation on fertility that feels less about nurturing life and more about exacting sacrifice. Judith’s firm stance on being child‑free becomes an act of revolt, a defiance against the village’s hereditary mandate. In a society that venerates lineage like a birthright, her autonomy reads as heresy.

Collective identity versus individual freedom plays out like a centuries‑old tug‑of‑war. The village operates as an entrenched matriarchy, demanding conformity under the guise of sisterhood. Judith’s urban rationalism clashes with this “communitarian creed,” exposing how tightly woven traditions can straitjacket a single soul. At moments I admired her resolve, then questioned if her isolation was self‑inflicted.

This is folk horror with a genealogical memory—Lower Austria as a vault of ancient superstitions. Deer carcasses appear less as gore and more as ecological omens, reminders of humanity’s tenuous pact with nature. Religious iconography—crosses half‑submerged in brambles—whispers of historical witch burnings and local inquisitions, as though the land itself remembers every atrocity.

Gender politics twist the narrative further. Toxic femininity replaces the expected patriarchy; men flit on the margins like ghosts, powerless and silenced. The film’s anti‑patriarchal edge feels refreshing, yet occasionally teeters into cliché. Perhaps it’s an intentional contradiction—after all, dogma thrives on binary certainties.

Rhythms of Dread and Disquiet

Prochaska’s pacing is a study in controlled release: the film simmers for prolonged stretches—Judith’s tentative steps through moonlit corridors, sighs of distant wind—before erupting in jagged bursts of terror. There are moments when the tension peaks so sharply it ricochets off the screen, and other stretches where it languishes, teasing us with the false comfort of routine (only to remind us that calm is merely a prologue to chaos).

The atmosphere feels tactile. You almost taste the damp earth of the forest, hear the echo of church bells warped by distance. Inside the inherited house, every creaking floorboard becomes a whispered secret. Red flags, cracked wallpaper and deer skulls accumulate like breadcrumbs leading deeper into obsession.

Emotionally, the film invites you to inhabit Judith’s unraveling. Her mounting panic—expressed in shallow breaths and widening pupils—becomes our own. When her world fractures, we feel the shards. The climax flirts with baroque excess—ritual flames licking at sanity—yet never fully abandons its earlier restraint. That tension between overload and minimalism is what gives the final act its unpredictable charge.

Aesthetic precision is undeniable. Rich color schemes and exacting soundscapes form the film’s backbone, while Richter’s performance anchors its leaps into surreal horror. Occasionally, genre conventions creak under the weight of their own lineage. Still, these moments of strain remind us that even well‑worn tropes can be reanimated with fresh purpose.

Full Credits

Director: Andreas Prochaska

Writers: Andreas Prochaska, Daniela Baumgärtl, Constantin Lieb

Producers: Tommy Pridnig, Clemens Wollein, Ulf Israel, Reik Möller

Cast: Julia Franz Richter (Judith), Reinout Scholten van Aschat (Ryan), Gerti Drassl (Aunt Paula), Maria Hofstätter (Mrs. Ramsauer), Gerhard Liebmann (Scheichl), Erika Mottl (Hannah Schatzenberger), Inge Maux (Mrs. Loidl), Linde Prelog (Mom Scheichl), Carmen Gratl (Mrs. Gebtesroither), Beatrix Brunschko (Mrs. Dorfner)

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): Carmen Treichl

Editor: Karin Hartusch

Composer: Karwan Marouf

The Review

Welcome Home Baby

Welcome Home Baby stakes its claim as a cerebral folk horror that marries exquisite atmosphere with a probing look at autonomy and tradition. Prochaska’s lush visuals and Richter’s fearless performance weave an immersive knot of dread, yet narrative leaps at times strain coherence. The result haunts long after the credits, inviting reflection on communal rites and personal agency.

PROS

- Exceptionally immersive atmosphere

- Julia Franz Richter’s magnetic central performance

- Thoughtful exploration of autonomy vs. tradition

- Striking production design and color symbolism

- Tension expertly balanced between slow burn and shocks

CONS

- Occasional reliance on familiar folk‑horror tropes

- Narrative logic stretches under supernatural weight

- Tilted‑angle cinematography can feel overused