The crime drama, a genre so saturated it often feels like a self-replicating algorithm, occasionally coughs up a specimen worth a prolonged stare. So arrives Dept. Q, transplanting its Danish literary DNA to the brooding, granite-faced city of Edinburgh – a shift that feels less like a simple change of scenery and more like a recalibration of inherent gloom. At its heart is the titular Department Q, a newly minted cold case unit; less a high-tech hub of forensic wizardry, more a subterranean archive of forgotten sorrows and stubbornly unclosed chapters. Think of it as the police force’s institutional attic, where dusty files whisper of justice long deferred.

The impetus for this little venture into investigative archaeology? Oh, the usual bureaucratic alchemy: a dash of public relations savvy (got to feed the true crime beast, after all) and a convenient way to shunt aside the decidedly inconvenient DCI Carl Morck. Morck, our central figure, is fresh from a rather nasty bit of on-the-job violence that left him, and his view of humanity, significantly more scarred. He’s a man whose trauma serves not as a mere plot point but as an existential compass, perpetually pointing towards a kind of bleak north. He was, one suspects, already halfway there before the bullets started flying.

What unfurls, then, promises not just a procedural churn but a dive into the murky waters of the human psyche. The series hints early at a commitment to exploring the how and the why, the messy internal landscapes of both hunter and hunted. There’s an immediate, palpable sense of damaged souls seeking not just answers for the dead, but perhaps a form of reparative coherence for themselves – piecing together the fragmented narratives of others as a way to mend their own. A grimly hopeful endeavor, if ever there was one.

Carl Morck: A Masterclass in Managed Dereliction

At the dyspeptic heart of Dept. Q beats the stubbornly irregular pulse of Detective Chief Inspector Carl Morck. Here we have the modern anti-hero meticulously rendered: a creature of profound crankiness, his misanthropy not so much a trait as a worldview, and an arrogance seemingly hard-wired, yet all this barnacled to a mind of undeniable, laser-like brilliance.

His disdain for his fellow humans (and, one suspects, himself on particularly bad days) is a long-cultivated garden, flourishing well before recent traumas watered its bitter roots. His people skills, if one could call them that, seem to have been modelled on a particularly surly badger. Adding a subtle, almost invisible spice to this stew of alienation is his Englishness adrift in the Scottish professional sea – another faint hum of ‘other’ in his already discordant symphony of self. He is, in essence, a walking, glowering refutation of the team-building exercise.

Then came the incident. A calamitous shooting, leaving one young officer dead, his partner Hardy confined to a wheelchair, and Morck himself physically scarred. This wasn’t just a bad day at the office; it was a full-blown existential demolition. The event acts as an accelerant to his already potent cynicism, layering on a guilt so thick it’s practically a physical presence, and forcing a rather unwelcome tête-à-tête with his own mortality.

His mandatory therapy sessions with the enviably patient Dr. Irving are less about healing and more a weekly sparring match, where Morck parries genuine insight with weaponized sarcasm. One imagines his internal monologue during these sessions could power a small, very cynical city.

Yet, to dismiss Morck as a mere caricature of the “brilliant bastard” cop would be to miss the faint, flickering light beneath the bushel of his awfulness. There are slivers of something more: the razor-sharp intellect untangling impossible knots, a capacity for feeling so deeply suppressed it’s practically subterranean, and surprising, almost begrudging, flashes of effective mentorship.

His attempts to articulate, or even acknowledge, an emotion are often exercises in spectacular clumsiness, the emotional equivalent of a man trying to assemble flat-pack furniture in the dark while wearing oven mitts. And then there’s the curious domestic tableau with Jasper, the sullen teenager under his roof – a daily reminder of human connection in its most bewildering, and perhaps to Morck, its most authentic, form. It’s in these cracks that the real, maddeningly complex human resides.

The Sub-Basement Salvagers: Dept. Q’s Motley Concord

Every dysfunctional institution needs its oubliette, a place to stow inconvenient truths and even more inconvenient personnel. For the Edinburgh police force, this takes the form of Department Q’s physical and spiritual home: a gloriously grim sub-basement, likely last renovated when linoleum was considered avant-garde.

With its charmingly inoperable urinals (a potent symbol, surely, of systemic impotence or perhaps just poor plumbing), this subterranean office is less a workspace and more a concrete manifestation of marginalization. Credit for this inspired piece of personnel management goes to Morck’s boss, Moira, who, with the kind of Machiavellian pragmatism that keeps bureaucracies chugging along, births Dept. Q chiefly to exile Morck and, presumably, redirect its meager funding towards shinier, more politically palatable ventures. It’s a masterstroke of passive-aggressive organizational strategy.

Into this atmospheric dungeon, a peculiar fellowship begins to coalesce, drawn like moths to a flickering, very dim bulb. There’s Akram Salim, a Syrian émigré whose past as a police officer in his homeland lends him a quiet, formidable competence that Morck, in his own chaotic way, comes to rely upon. Akram navigates the alien corridors of Scottish law (and Morck’s moods) with an intelligence and resourcefulness that suggest a profound understanding of how order is made and unmade – a perspective perhaps sharpened by experiences far removed from Edinburgh’s cobblestones.

He’s the still point in Morck’s turning, often exasperating, world. Then there’s Rose Dickson, a young constable whose peppy demeanor and actual people skills seem almost offensively cheerful in the gloom. Recovering from her own psychic wounds that had her desk-bound, Rose sees Dept. Q not as a professional graveyard but as a proving ground, her eagerness a stark, sometimes jarring, contrast to Morck’s cultivated ennui. Completing this initial trio of the damned (or at least, the deeply inconvenienced) is DS Hardy, Morck’s paralyzed former partner, contributing his sharp mind from the confines of a hospital bed, a poignant testament to loyalty outlasting calamity.

What emerges is a classic ‘island of misfit toys’ scenario, where individual traumas, rather than being solely debilitating, become a strange, unacknowledged common language. This is where Dept. Q flirts with something genuinely touching: the notion of reparative detection, where these fractured individuals, in sifting through the cold embers of other people’s tragedies, find a measure of purpose, if not outright healing, for themselves.

Their interactions are a fascinating dance of clashing neuroses and slowly dawning mutual respect – an unconventional, often hilariously awkward, but ultimately functional ecosystem. The banter, when it surfaces, is as dry as the dust in their forgotten files, a necessary release valve in the pressure cooker of their collective angst.

The Gordian Knot: Dept. Q’s Narrative Labyrinth

The engine driving Dept. Q’s descent into the chilly archives of crime is, naturally, its first major exhumation: the vanishing of prosecutor Merritt Lingard. Lingard herself is sketched as a figure of fierce, almost abrasive dedication – a spiritual cousin to Morck in her dogged, perhaps self-isolating, pursuit of what she deems right. Her backstory, involving a powerful man accused of dispatching his wife (the method: a convenient staircase) and her own subsequent, mysterious tumble from a ferry, provides the requisite cocktail of high stakes and murky circumstance. It’s fertile ground for any detective, let alone one already tilling the barren fields of his own soul.

Scott Frank and his co-creators opt for a layered, almost sedimentary, approach to storytelling. Morck’s internal wrestling match with his own considerable demons, alongside the slow-burn inquiry into the ambush that nearly ended him, runs concurrently with the Lingard investigation. This creates a kind of narrative echo chamber, where past and present traumas speak to each other, sometimes illuminatingly, sometimes just adding to the general gloom. The pacing is one of leisurely confidence, a slow unfurling that dedicates ample time to character nuance – a nine-episode sprawl for a single primary case.

This is the modern streaming series’ gamble: that such an extended stay will enrich the journey, though one might occasionally wonder if a slightly more aggressive editorial hand could have tightened certain meanders. Merritt’s own story, for instance, is presented in parallel, offering tantalizing glimpses that both inform and obscure, a fragmented perspective on a life interrupted. And yes, an early, rather shocking plot development yanks the rug with considerable force, effectively signaling that the narrative path ahead may be less than straightforward.

Thematic tendrils snake out from the Lingard case, tangling with issues of historic injustice, the corrupting influence of power, and the quiet agony of unresolved loss (a missing necklace, for example, becomes a potent symbol of stolen futures). Each overturned stone in the investigation seems to uncover not just clues, but deeper strata of human suffering and institutional compromise.

The actual “whodunit,” when it finally surfaces, is an intricate construction, a web of personal vendettas and grim opportunism. Whether its ultimate architecture feels entirely sound or teeters into the mildly convoluted – and whether its central mysteries are held close for precisely the right duration – will likely be a point of pleasing contention amongst viewers. Sometimes the journey, one must admit, is more compelling than the precise schematics of the destination.

The Patina of Pain: Dept. Q’s Atmospheric Soul

Visually, Dept. Q luxuriates in a palette of bruised skies and shadowed interiors, a symphony of sulky grays and blues that does more than just set a mood; it seeps into the very bones of the narrative. This is a world perpetually caught in a state of twilight, both literal and metaphorical. Director Scott Frank, wielding a quietly confident lens, isn’t afraid of stillness, nor of subtle visual cues – a shift in aspect ratio for a significant setting, a gentle drift of focus between characters (say, from Morck to Akram) that speaks volumes about burgeoning understanding without a word uttered.

The production design, particularly the infamous basement headquarters of Dept. Q, is a masterpiece of evocative squalor. It’s a space so rich in dynamic visual clutter and institutional neglect (those urinals again, bless them) that it becomes less a set and more a tangible symbol of the forgotten and the flawed.

Edinburgh itself is sculpted into more than a mere picturesque backdrop of castles and cobblestones. Initially, perhaps, the camera plays the tourist, but it soon settles into a more intimate, workaday portrayal of the city, finding character in its slate skies and the stern lines of its architecture. The city breathes with a history that feels consonant with the cold cases pulled from its depths; its ancient beauty is a counterpoint to the very modern miseries unspooled within its streets. It’s a place that seems to hold its secrets close, much like the individuals who populate its shadowed corners.

This carefully crafted atmosphere serves as a potent amplifier for the series’ deeper thematic currents. The pervasive gloom mirrors the internal landscapes of guilt and trauma carried by its protagonists. Questions of moral ambiguity – the thorny issue of flawed individuals employing questionable methods in pursuit of a greater good – feel particularly resonant in these dimly lit spaces.

The series forces a constant negotiation with this “cognitive dissonance,” compelling viewers to inhabit that uncomfortable space where detectives steeped in humanity’s darkest impulses must attempt to navigate, or at least project, a semblance of normalcy. It’s a stark reminder that justice, like the city itself, is often a complex, layered, and frequently untidy affair.

Faces in the Gloom: The Performances Illuminating Dept. Q

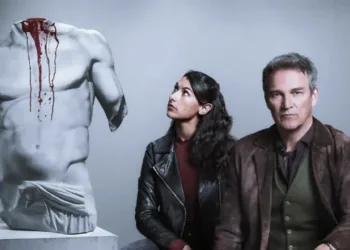

A series steeped in such atmospheric mire and psychological murk demands performances that can both inhabit and transcend the gloom. Dept. Q delivers, anchored by Matthew Goode’s compelling turn as Carl Morck. Goode, often seen striding through period dramas with an air of well-bred ennui, here revels in a scruffier, more visceral register.

He perfectly captures Morck’s cocktail of biting sarcasm, profound melancholy, and a pain so deep it’s almost tectonic, all shielded by that “transparently self-protective arrogance” which barely conceals the walking wound beneath. It’s a performance that makes the insufferable surprisingly, if sometimes reluctantly, sympathetic.

The ensemble orbits this prickly sun with admirable skill. Alexej Manvelov as Akram is a study in potent understatement, his quiet intensity a grounding force. Leah Byrne brings a vital spark as Rose, navigating her character’s trauma with a compelling blend of moxie and vulnerability.

Kelly Macdonald, as the long-suffering Dr. Irving, radiates a wry warmth that cuts through Morck’s defenses (or tries to), while Kate Dickie’s Moira is the quintessential weary, perma-grimacing superior, a figure of pure, undiluted institutional exasperation. Jamie Sives offers Hardy’s resilient charm from the sidelines, and Chloe Pirrie imbues Merritt Lingard with a fierce, almost feral, determination.

Collectively, this cast, particularly the strong contingent of Scottish actors lending an indispensable authenticity to the Edinburgh setting, creates a believable ecosystem of flawed humanity. Their interactions, even when abrasive, feel rooted in a shared, if unspoken, understanding of the world’s rougher edges. They ensure that Dept. Q, for all its stylistic flourishes and narrative complexities, remains tethered to the human heart.

Dept. Q premiered on Netflix on May 29, 2025. The series is a British adaptation of Jussi Adler-Olsen’s Danish crime novels, relocated to Edinburgh. It follows Detective Chief Inspector Carl Morck (Matthew Goode), a brilliant but emotionally scarred detective assigned to lead a cold case unit. Alongside his diverse team, including a Syrian investigator and a cadet coping with PTSD, Morck delves into unresolved cases, uncovering deep-seated corruption and personal traumas.

Full Credits

Directors: Scott Frank

Writers: Scott Frank, Chandni Lakhani, Stephen Greenhorn, Colette Kane

Producers: Andy Harries, Rob Bullock

Executive Producers: Scott Frank, Andy Harries, Rob Bullock

Cast: Matthew Goode, Kelly Macdonald, Chloe Pirrie, Alexej Manvelov, Leah Byrne, Mark Bonnar, Jamie Sives, Shirley Henderson, Kate Dickie

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): David Ungaro

Composer: Carlos Rafael Rivera

The Review

Dept. Q

Dept. Q masterfully excavates the bleakly compelling corners of the human condition, wrapped in Edinburgh's atmospheric gloom. While its narrative deliberation may test the impatient, the series rewards with richly drawn, tormented characters, a hauntingly immersive world, and stellar performances across the board. It’s a meticulously crafted, if occasionally meandering, journey into the shadows, offering a sophisticated, psychologically acute addition to the crime genre that lingers long after the case is closed. This is intelligent television that respects its audience.

PROS

- A magnetic and deeply complex protagonist in DCI Carl Morck.

- Superb ensemble cast embodying a memorable "misfit alliance."

- Hauntingly evocative Edinburgh atmosphere and a strong, deliberate visual style.

- Intelligent, multi-layered writing exploring rich thematic territory.

- Matthew Goode's transformative and compelling lead performance.

CONS

- The deliberate, leisurely pacing might feel elongated or slow for some viewers.

- The central mystery, while intricate, can occasionally veer towards the convoluted.

- Some character archetypes, though well-played, tread familiar ground.