The story of Dracula has become so ossified in our cultural memory, its beats so familiar, that it practically serves as a modern myth. We know the hero, Van Helsing, wins. But Natasha Kermani’s film asks a deeply uncomfortable question, one rarely posed about our monster-slayers: what happens next? What becomes of the victor when the war is over and the only thing left to fight is the narrative residue clinging to his family?

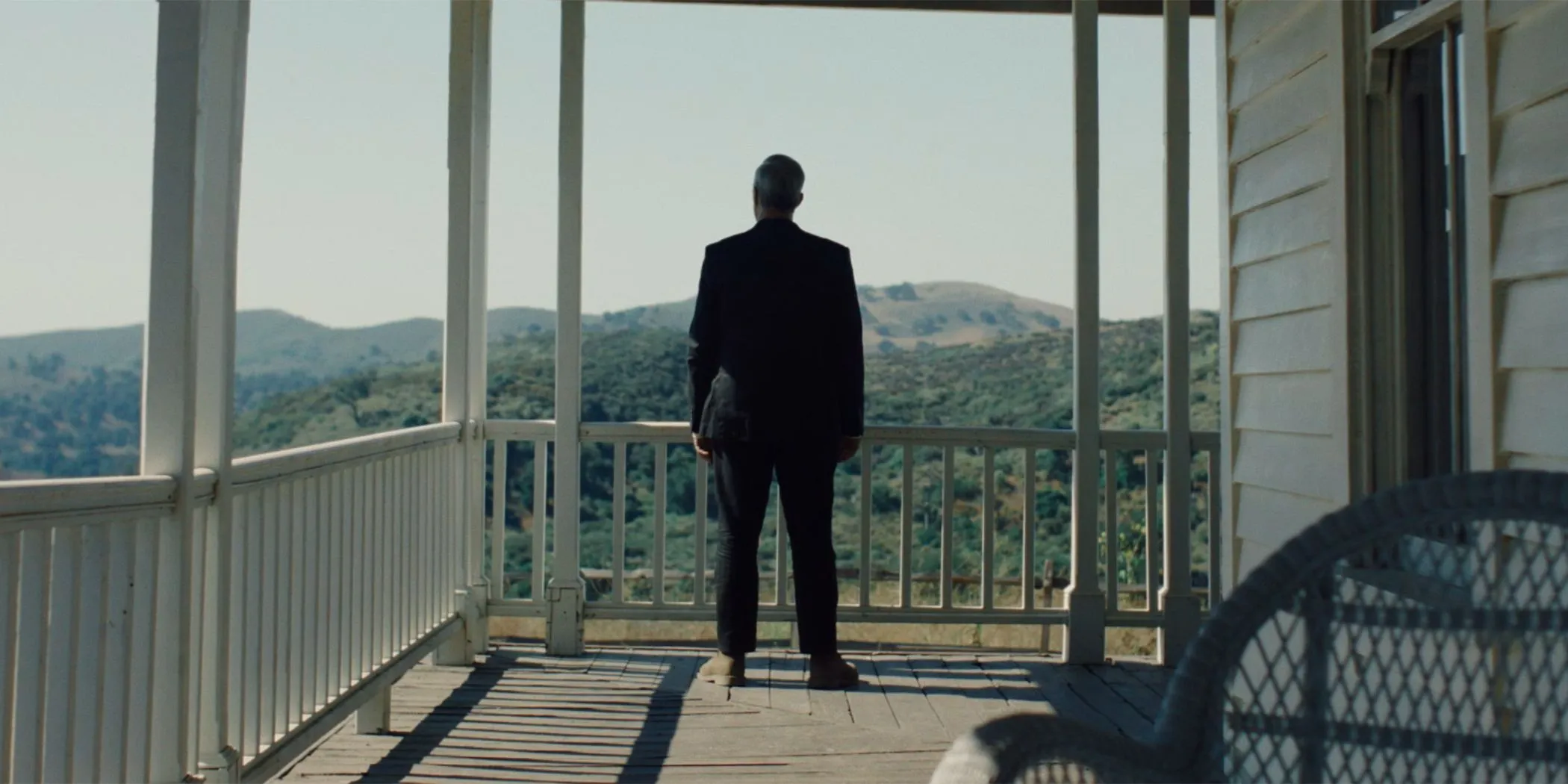

The answer is found in an arid, sun-punished California idyll, a location so antithetical to Gothic gloom it feels like a deliberate provocation. Here, Abraham Van Helsing lives in a state of paranoid exile with his wife Mina and their two sons.

This is Van Helsing’s retirement phase (if you can call it that), less a celebrated academic and more a petty tyrant of the homestead. When a strange malady, seemingly born from Mina’s past trauma, takes hold, Abraham’s old pathology resurfaces. The tools once meant for a creature of the night are dusted off for a threat that may be entirely within the home, forcing a re-examination of who the real monster has been all along.

The Tyranny of the Good Man

The Van Helsing we meet is not the dogged intellectual of Stoker’s novel. He is a man pickled in his own legend, a patriarch whose authority rests on a single, unrepeatable event from two decades prior.

His sons, Max (our conduit into this strange world) and the younger Rudy, have been raised in this vacuum, their reality shaped by a father who conflates safety with total submission. Their education is a curriculum of fear, a kind of extreme homeschooling in the art of monster-hunting for monsters that never appear.

At the center of this tension is Mina, the family’s ghost at the feast. Her ailment is deliberately obscure—is it the lingering touch of vampirism, a form of nineteenth-century post-traumatic stress, or the mind simply breaking under the strain of her husband’s protective pathology? She is the household’s living wound.

This fragile stasis shatters with the approach of modernity. The sound of a new railroad signals the world’s intrusion, an unforgivable breach of Abraham’s quarantine. This, paired with Mina’s worsening state, sends him into a spiral of righteous paranoia.

As Max watches his father prepare for a war only he can see, the boy’s perception begins to shift. The lessons in vampire slaying feel less like preparation and more like an indoctrination. Each act of “protection” becomes another bar on the cage, forcing the narrative’s chilling question: Is father a shield against the dark, or is he the darkness itself?

The Poison in the Bloodline

The film’s most potent intellectual exercise is its inversion of the monster story. It posits that the most terrifying monster is the one who believes, with absolute certainty, that he is the hero. Van Helsing’s legacy is systematically dismantled, not by a resurrected Dracula, but by the camera’s unblinking gaze on his “heroic” methods. From his sons’ perspective, the rituals of protection—the confinement, the psychological manipulation, the looming threat of physical purification—are identical to the acts of a captor.

This is not horror born of fangs and shadows. It is the quiet, suffocating terror of domestic absolutism, the dread of living under a man whose love is conditional upon your belief in his demons. He runs a one-man moral panic from the front porch.

This pathology is, of course, hereditary. Not through blood, but through doctrine. The film’s treatment of inherited trauma is its intellectual centerpiece. Max and Rudy are not merely sons; they are conscripts in their father’s psychic war, groomed to fear a world they cannot see and to accept his violence as a form of love.

The true vampiric curse on display is this passed-down paranoia, a poison in the bloodline that perpetuates a cycle of control. The horror is watching the children begin to absorb the twisted logic of their keeper. Whether a literal Count is pulling the strings from afar becomes an almost trivial point. The fear inside the house is real. The damage is the point.

The Geometry of Dread

For a film so reliant on internal states, the execution of its mood is everything. Director Natasha Kermani demonstrates a formidable control of tone, steeping every frame in a low, simmering dread that feels almost physical. This is horror by subtraction.

Kermani consistently denies the audience the catharsis of a jump scare or a monstrous reveal, instead forcing us to sit in the unbearable quiet between threats. The unease is entirely atmospheric, generated by a held gaze or the oppressive weight of a silent room. It’s a bold choice, demanding immense patience.

This mission is realized through Julia Swain’s magnificent cinematography. The film looks less like a horror movie and more like a collection of lost American paintings, finding a deep menace in the mundane. By day, the aesthetic is a kind of Agoraphobic Western: the sun-bleached plains of California feel not liberating but exposing, an empty stage where the family’s dysfunction is cruelly illuminated. The horror is in the harsh light. At night, the shadows are absolute.

The decision to use the boxy 4:3 aspect ratio is a masterstroke of thematic reinforcement. The vast landscape is perpetually squeezed by the frame, visually trapping the characters and the audience right there with them. The cage is the camera.

Human Scaffolding for an Abstract Dread

An atmospheric film like this lives or dies on its human anchors. Titus Welliver’s Abraham is the gravitational center, a performance of immense, stoic weight. He plays the patriarch with a calcified certainty, his slow voice delivering pronouncements as if they are scripture.

Welliver never winks; he gives Abraham the dignity of his conviction, which makes his potential madness all the more frightening. You believe that he believes. He is the immovable object.

If Welliver is the object, Jocelin Donahue’s Mina is the unstoppable force of suffering. Her performance of brittle fragility rejects any simple reading of madness. Donahue channels a lineage of Gothic heroines—women trapped by circumstance and gaslit by those meant to protect them. Her pain is the film’s one undeniable truth, grounding its high-minded ideas in a body quietly collapsing.

Caught between these two poles is Brady Hepner as Max, our eyes in this domestic vortex. His performance charts the film’s emotional course, registering the chilling changes in the atmosphere his parents generate as duty gives way to dawning horror.

The Promised Monster Never Arrives

A word of caution is necessary regarding the film’s tempo. The narrative is constructed from long, quiet moments, its pace methodical to the point of being glacial. This minimalist structure, a clear echo of its short story origins, builds a consistent dread but offers precious little release.

It is a demanding, sometimes repetitive watch, a film that risks alienating the very audience it purports to court. The tension is all sizzle and no stake. This brings us to the film’s central, audacious gambit.

This is a Dracula story with almost no Dracula. The marketing promises a monster that the filmmakers have no intention of delivering. This act of narrative denialism is the whole point, using a famous brand name to smuggle in a bleak meditation on familial abuse.

For anyone who came for fangs and bats, the experience will feel like a swindle. For those prepared for a story where the most dangerous monsters are the ones who share your name, the film offers its own severe, unsettling rewards.

Abraham’s Boys: A Dracula Story will premier in U.S. theaters on July 11, 2025, via IFC Films.

Full Credits

Director: Natasha Kermani

Writers: Natasha Kermani, Joe Hill

Producers and Executive Producers: Leonora Darby, James Harris, James Howard Herron, Nicholas Lazo, Mark Ward, Tim Wu, Samuel Zimmerman

Cast: Titus Welliver, Brady Hepner, Judah Mackey, Jocelin Donahue, Aurora Perrineau, Jonathan Howard, Larry Cedar, Corteon Moore, Fayna Sanchez, Paul Wong, Forrest McClain, Nick Epper, Dalton Simons

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): Julia Swain

Editor: Gabriel de Urioste

Composer: Brittany Allen

The Review

Abraham's Boys: A Dracula Story

A challenging and artistically rendered deconstruction of a legend, Abraham's Boys succeeds as a bleak meditation on domestic tyranny. It is anchored by commanding performances and a masterfully crafted atmosphere of dread. However, its glacial pace and deliberate subversion of genre expectations make it a difficult, even frustrating, watch. A film to be admired for its craft and audacity, though perhaps not universally enjoyed.

PROS

- Stunning, painterly cinematography.

- Powerful lead performances from Titus Welliver and Jocelin Donahue.

- Masterful, dread-filled atmosphere.

- Intellectually rich themes of trauma and abuse.

- Brave subversion of genre tropes.

CONS

- Extremely slow and methodical pacing.

- Narrative can feel repetitive and lacks action.

- Will likely disappoint viewers expecting a traditional vampire film.

- A demanding and not easily accessible viewing experience.