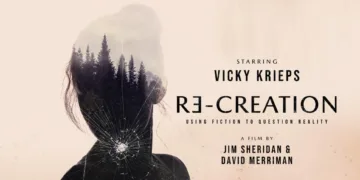

There are ghosts that haunt the Irish landscape, and then there are the stories we build to contain them. “Re-creation” is one such story, a strange seance of a film that does not seek to solve a crime but to inhabit the space of its uncertainty. It begins with the cold facts of a real wound: the 1996 murder of Sophie Toscan du Plantier, her body found outside her West Cork cottage.

It acknowledges the prime suspect, journalist Ian Bailey, a man tried and convicted by French courts from afar but never formally charged on Irish soil. From this unresolved history, the film poses a speculative question that spirals into an existential abyss: What if a jury of twelve Irish citizens had been locked in a room to find a truth?

The film immediately abandons the pretense of a whodunnit. It is not an investigation of evidence, but a haunting exploration of how human beings assemble a reality, how we forge conviction from the unstable elements of memory, pain, and shadow.

The Architecture of Doubt

The jury room is a purgatory, a hermetically sealed chamber where the air grows thin with the weight of a life and a death. Within these four walls, twelve souls are tasked with the divine act of judgment, yet they bring with them all the unhealed fractures and whispered traumas of their mortal lives.

The proceedings begin with the hollow clang of a near-unanimous verdict, a desperate rush to closure and the comfort of a shared story. This fragile consensus is immediately stopped by a single, quiet fissure. That fissure is Juror #8, played by Vicky Krieps with a profound stillness that feels less like active opposition and more like a different state of being.

Her dissent is not a declaration of another truth, but an insistence on honoring the void where a truth should be. It is a rebellion against the violence of certainty. Her performance is a study in controlled gravity, her doubt a physical presence in the room, visible in the tension of her jaw and the careful, deliberate way she occupies her chair.

In direct opposition is the firestorm of Juror #3, whom John Connors imbues with a desperate, furious need for a guilty verdict. His certainty is a shield against the horror of the unknown, an existential anchor in the chaos of a brutal, meaningless act.

His rage feels born of a deep, personal wound, a place where justice must look a certain way to keep the world from falling apart. Their conflict becomes the film’s agonizing pulse, a dialectic between the abyss and the desperate human need to build a bridge over it.

Through their battle, which is at once philosophical and deeply personal, the private histories of the other jurors begin to bleed into the sterile room. The space transforms into a confessional, where their own encounters with violence, betrayal, and failed justice rise like specters to shape their perception of the case, proving that no judgment is ever truly impersonal.

Summoning the Tangible

The film exists in a liminal space, its narrative woven from the threads of documentary and fiction, a ghost haunting its own machine. The specter of the real case permeates the chamber, with news clippings and archival footage anchoring the invented drama in a history that cannot be denied or escaped.

This creates a disquieting tension, as the fictional deliberation is constantly contaminated by the unshakable gravity of real death. Co-director Jim Sheridan’s choice to place himself within the drama as the jury foreman is a profound and unsettling self-implication.

He is not merely a storyteller but a participant, a Charon-like figure guiding the jury through this shadowy space between fact and its reconstruction, all while grappling with his own decades-long obsession with this specific darkness. His presence asks if a filmmaker can ever be a neutral observer, or if the very act of telling a story is a form of manipulation.

The film’s most arresting moments occur when the jurors abandon intellectual debate and attempt a form of resurrection. They darken the room, casting long shadows on the walls, and begin to physically trace the final, violent steps of the victim and her assailant.

These scenes are less re-enactment and more secular ritual, a desperate, almost primal attempt to understand a physical truth through the imperfect vessel of communal empathy. They try to feel the cold night air, the terror, the weight of the weapon, as if to commune with the kinetic reality of the event.

The experience is an attempt to make the abstract horror tangible. The film’s occasionally abrupt editing and the fleeting, silent glimpses of Colm Meaney’s Ian Bailey, a man rendered a voiceless icon by media saturation, only amplify this sense of fragmentation. The style reflects the subject: a truth that remains stubbornly, horrifyingly incomplete.

An Autopsy of Conviction

To seek a resolution to the murder of Sophie Toscan du Plantier here is to fundamentally misread the film’s purpose. The movie is not a key to a locked room; it is a mirror. It places our modern cultural obsession with true crime under a microscope, dissecting the viewer’s own hunger for a neat narrative conclusion that real life so rarely affords.

It asks what psychological need this genre feeds, what personal demons we are attempting to exorcise when we appoint ourselves detectives of another person’s tragedy. “Re-creation” inspects how the very notion of objective truth dissolves under the immense pressure of personal experience. The film proposes that truth is not found, but constructed.

The jurors, and by extension the audience, project the ghosts of their own pasts onto the opaque figure of the accused, making him a canvas for their fears, their rage, and their unresolved sorrows. The case becomes a vessel for everything they carry inside themselves.

The film does not champion an answer; it champions the sanctity, the moral necessity, of doubt itself. It suggests that in a world so quick to condemn, a world that craves the sugar rush of instant judgment, the most ethical and courageous act might be to hesitate.

It is a call to question the foundations of our own certainty, to acknowledge the dark and complex places from which our strongest convictions often spring. This is a film about the anatomy of belief, a stark and unflinching portrayal of how our certainties are constructed not from solid, impartial fact, but from the fragile, haunted, and deeply personal architecture of our own lives. It is an autopsy of conviction, laying bare the sinew and gristle of how we decide what is true, and it leaves the final, unsettling incision to us.

Re‑Creation is a hybrid courtroom drama and mystery-thriller that premiered at Tribeca Film Festival in June 2025.

Full Credits

Director: Jim Sheridan, David Merriman

Writers: Jim Sheridan, David Merriman

Producers and Executive Producers: Fabrizio Maltese, Tina O’Reilly

Cast: Vicky Krieps, Jim Sheridan, Aidan Gillen, Colm Meaney

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): Carlo Thiel

Editors: Jack Thornton

Composer: Anna Rice

The Review

Re-creation

"Re-creation" is less a film to be watched and more a philosophical condition to be experienced. It masterfully uses the ghost of a real tragedy to perform an autopsy on the very anatomy of conviction, forcing an uncomfortable but essential look at how we construct truth from the fragments of our own lives. While its deliberately unresolved and fractured nature will challenge many, it stands as a potent, unsettling, and vital piece of cinema for those willing to sit with the profound darkness of uncertainty.

PROS

- Powerful and deeply committed lead performances, especially from Vicky Krieps and John Connors.

- A profound philosophical examination of doubt, belief, and the nature of justice.

- An innovative and unsettling blend of fictional drama with documentary elements.

- Haunting and effective re-enactment scenes that transcend typical legal drama.

CONS

- Its unconventional structure offers no narrative closure, which may frustrate viewers seeking answers.

- The editing style can feel abrupt and fragmented at times.

- The relentlessly contemplative and somber pace may not appeal to a wide audience.