“Winter in Sokcho” marks the cinematic debut of Koya Kamura, who adapts Elisa Shua Dusapin’s sparse novel for the screen. Premiering at international festivals, this French-Japanese co-production greets viewers with a hushed tension. In the thin air of Sokcho’s frozen seafront—a fishing town curled against the Demilitarized Zone—each breath seems to linger, each footstep echoes.

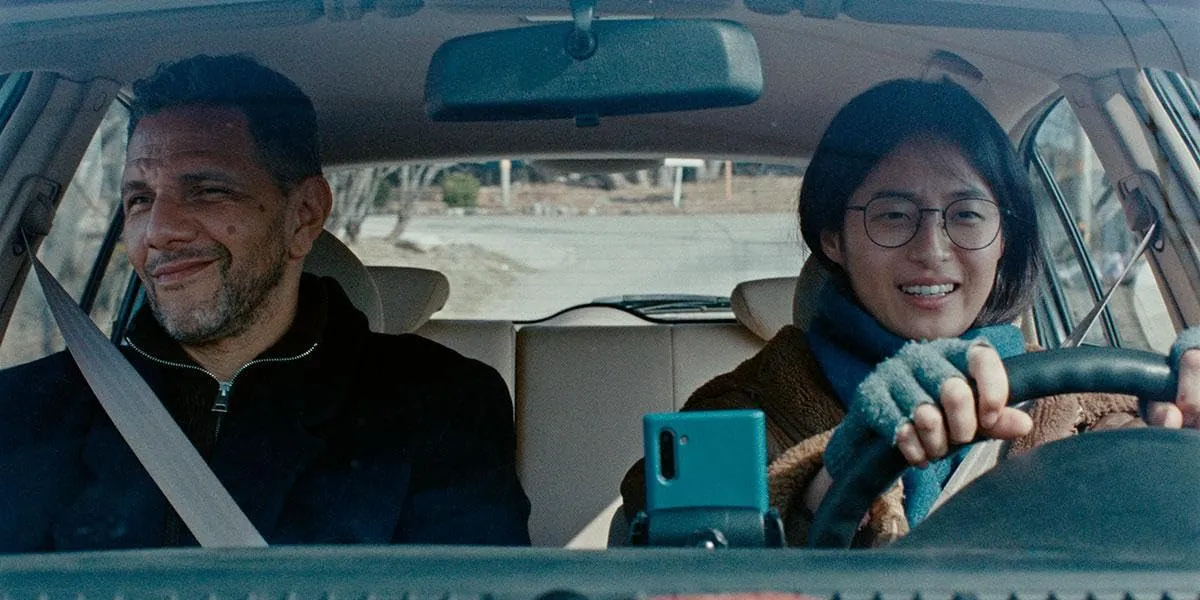

Soo-Ha, portrayed with inscrutable grace by Bella Kim, moves through her days at a boarding house as though trapped in slow motion. Her solitude is punctuated only when Yan Kerrand, a French illustrator played by Roschdy Zem, arrives in search of raw inspiration. His presence pries open the townsfolk’s routine and awakens buried questions in Soo-Ha’s heart.

Kamura’s pacing is deliberate, a rhythm of long silences and half-heard murmurs. Scenes unfurl like low-temperature ink stains spreading across paper—quiet, inevitable, and oddly beautiful. Here, the film’s muted palette and reflective tempo hint at unspoken desires and the ache of unclaimed histories.

This review will examine how identity fractures and reconnections emerge through storytelling choices, performances, and visual design—inviting us to witness how two solitary souls orbit, clash, and perhaps illuminate one another.

Narrative & Thematic Exploration

The story threads through Soo-Ha’s measured routine: dawn’s gray light on empty docks, the clink of dishes in the boarding house kitchen, evenings spent helping her mother at the fish market. Yan’s arrival jolts that inertia—his notebooks of sketches become maps to her own buried memories. Curiosity blooms first like frost flowers, then deepens into something more tangled.

Kamura probes isolation as both shelter and prison. The winter landscape mirrors Soo-Ha’s inward quietude, yet its vast emptiness mocks any hope of true escape. Her dual heritage—Korean upbringing shadowed by a father she never knew—creates a fissure she cannot heal alone.

In their encounters, power shifts: Yan observes with an artist’s detachment, while Soo-Ha oscillates between guide and enticer, muse and investigator. Is her devotion genuine, or does she feed his creativity at the cost of her own sense of self? Each shared glance and stiff-shouldered meal probes whether art can reveal truth or only reshape it.

Crossing the DMZ, they tread a borderland of division that bleeds into their bond. Proximity to North Korea becomes a silent metaphor for longing: a desire for connection that hovers just beyond reach.

Characterization & Performances

Soo-Ha wears her winter coat like armor—oversized, concealing. Bella Kim communicates inner storms with subtle gestures: a reluctant lift of her chin, a fingertip tracing steam on a glass. The film hints at her disordered eating through fleeting shots—a half-eaten meal discarded, a gaze that lingers on others’ reflections—yet Kim never allows pity. Instead, she embodies a character caught between self-erasure and self-discovery.

Yan moves with deliberate stillness. Zem’s voice carries a soft timbre, as if each word were chosen to disturb the air just enough. His goal—to capture “authentic” Korea—clashes with his outsider status. He sketches empty alleys and the weathered faces of locals, believing distance grants clarity. Yet his aloofness fractures under Soo-Ha’s persistent gaze.

Early on, Soo-Ha serves tea and translates menus; later, she parses Yan’s half-spoken musings, bridging two worlds. Their bond thickens around shared meals—two chopsticks crossing like poetry—and warps when she spies on his private work. Intimacy feels transactional, a convergence of loneliness rather than passion.

Soo-Ha’s mother, stooped and solemn, anchors her daughter to tradition and responsibility. Her high-school boyfriend, with his dreams of Seoul glamour, embodies superficial escape. Both frame Soo-Ha’s struggle: stay tethered or risk losing herself entirely.

Cinematic Craft & Atmosphere

Kamura favors long, unbroken takes that let viewers inhabit Sokcho’s hush. A frame may hold two characters frozen in mid-gesture, the silent interval swelling with unspoken dread. These pauses become claustrophobic, as if the camera itself hesitates to intrude.

Élodie Tahtane’s lens bathes each shot in cold blues and muted grays. Snow-streaked streets and wind-battered piers appear both desolate and exquisite. Occasionally, steam—rising from a hot bowl or a sauna—blurs faces, suggesting the fragility of perception.

Abstract watercolor animations flicker across the screen, their white-on-black strokes echoing Soo-Ha’s fragmented psyche. These visions surge without warning, like memory leaking into the present.

Sound design balances the hush of winter wind against Delphine Malausséna’s guitar-tinged score, which edges scenes with a distant ache. The crack of fish scales underfoot, the hollow echo of an unused jetty, each ambient note underscores how living at a border warps one’s sense of belonging.

Props—ink bottles, raw seafood, half-glazed ceramics—serve as extensions of character. Food is ritual and gatekeeper: a way to share intimacy or to fortify distance. Together, these elements coalesce into a sensory study of waiting, watching, and the uneasy promise of thaw.

Winter in Sokcho premiered in the Platform Prize program at the 2024 Toronto International Film Festival and was subsequently screened in the New Directors program at the 72nd San Sebastián International Film Festival.

Full Credits

Director: Koya Kamura

Writers: Koya Kamura, Stéphane Ly-Cuong

Producers: Fabrice Préel-Cléach, Yoon Seok-Nam

Cast: Bella Kim, Roschdy Zem, Park Mi-hyeon, Ryu Tae-ho, Doyu Gong, Jung Kyung-soon

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): Élodie Tahtane

Editor: Antoine Flandre

Composer: Delphine Malausséna

The Review

Winter in Sokcho

This painterly tale of solitude and longing lingers with its quiet tension, anchored by Bella Kim’s magnetic stillness and Kamura’s precise visual poetry. It may not satisfy those seeking clear resolutions, but its haunting mood and existential depth reward patient viewers.

PROS

- Bella Kim’s nuanced performance conveys deep emotion through stillness

- Koya Kamura’s framing transforms Sokcho’s winter landscape into a character

- Watercolor animations offer a visceral glimpse into Soo-Ha’s psyche

- Sound design and score underscore the film’s lingering tension

- Exploration of identity and solitude feels both intimate and universal

CONS

- Deliberate pacing may test viewers’ patience

- Ambiguous ending leaves narrative questions unresolved

- Sparse dialogue can feel too elliptical for some

- Supporting characters remain underdeveloped

- Thematic richness occasionally overwhelms plot momentum