For years, the terror of Five Nights at Freddy’s was rooted in confinement. You were trapped in a box, a tiny office where threats came to you. Secret of the Mimic rips that box open, letting the fear seep into a much larger space. Here, you are an “asset retrieval specialist,” a detached corporate title for someone sent into the sprawling, dust-choked halls of Murray’s Costume Manor.

This location is a boneyard of discarded identities, rows upon rows of mascot suits staring out with glassy eyes. Your job is to find one specific prototype lost within this mausoleum: an endoskeleton known only as The Mimic.

The game’s core idea creates a different kind of dread, one that feels reminiscent of the quiet paranoia in a film like John Carpenter’s The Thing. The threat is not a creature hunting you down a hallway; it is the potential for any object in the room to become the creature. It trades the immediate panic of a closing door for the deep-seated suspicion of scanning a room full of silent monsters, knowing only one is real. What happens to horror when it is stretched so thin, becoming everywhere and nowhere at once?

A Story Told in Static and Rust

Secret of the Mimic makes a deliberate choice to guide you through its darkness. Unlike the near-silent isolation of the original games, you are constantly connected to a voice on the radio, a snarky guide named Dispatch. This approach, having a “man in the chair,” is common in games like BioShock or Firewatch, creating a relationship that grounds the player.

Here, the effect is complicated. Dispatch’s sarcastic commentary often clashes with the oppressive atmosphere of the manor, creating a strange tonal dissonance. One moment you are holding your breath, listening for footsteps, and the next a joke cuts through the tension. This decision feels like it wants to give the game more personality, but it sometimes comes at the cost of pure, undiluted dread.

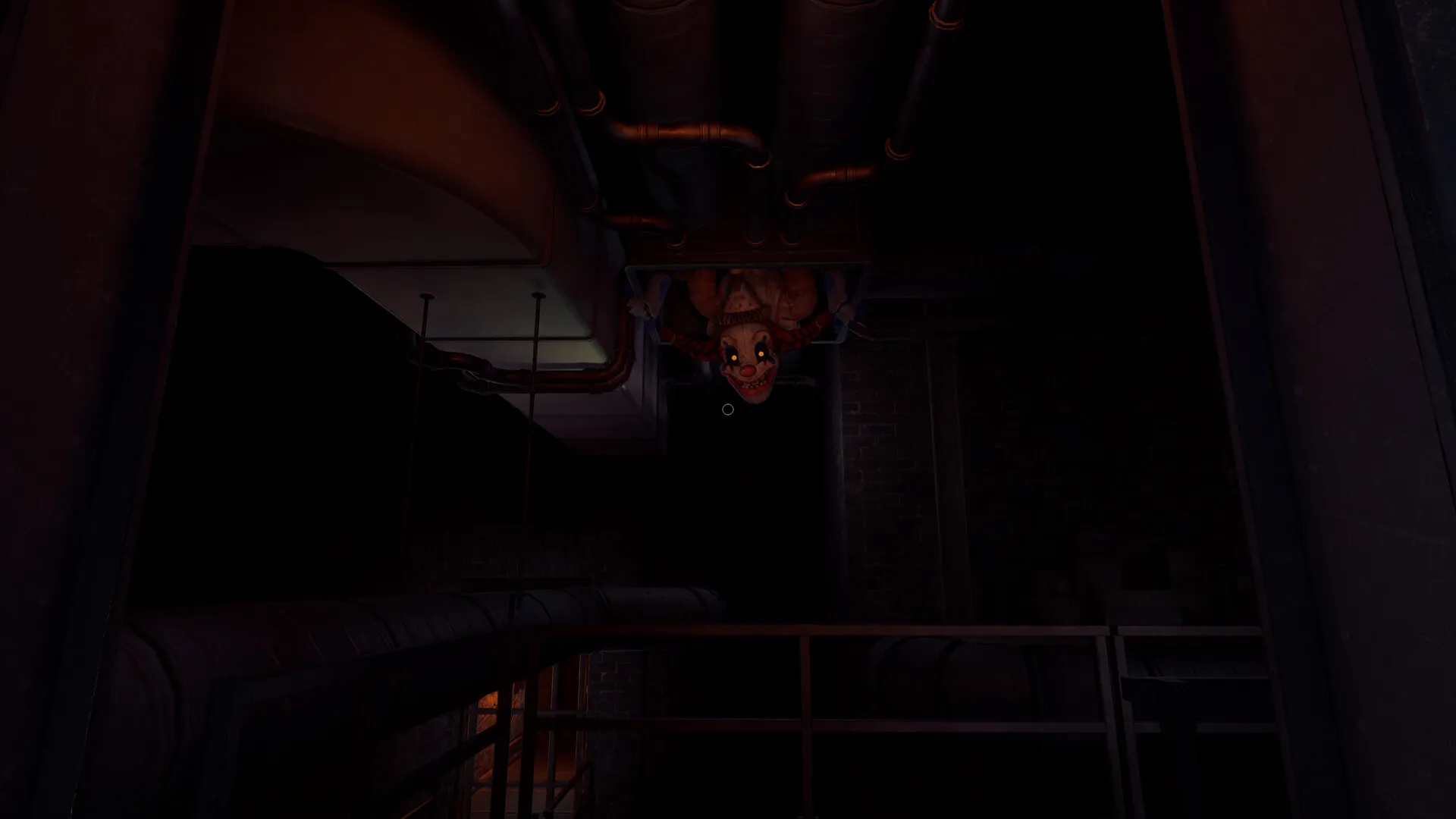

The setting itself tells its own story. Murray’s Costume Manor is a masterclass in environmental narrative, a world built from a “cassettepunk-meets-industrial” aesthetic. It swaps the ’80s neon of Security Breach for the grime of the ’70s—a place of humming analog equipment, forgotten machinery, and deep shadows.

This is a colder, more mechanical kind of decay. The horror is not just in the potential for a costume to spring to life, but in the oppressive feeling of the building itself, a forgotten relic of obsolete technology. It feels less like a haunted pizza place and more like a derelict film set where the props were left to rot.

This clearer storytelling extends to the lore, which is presented through voiced cutscenes and direct exposition. For longtime fans, this is a treasure trove of new information and connections. For a newcomer, it can feel like being dropped into the middle of a conversation.

The plot points are so deeply entangled with a decade of established history that they can lack weight without that prior investment. By making its story more explicit, does a series built on whispers and interpretation risk losing the very mystery that made it so captivating?

A Predator with Predictable Patterns

The design of The Mimic is, on paper, a brilliant evolution of horror. A shapeshifting antagonist that can inhabit any of the lifeless shells in a costume factory is a concept that should produce constant, unbearable tension. In the opening hour, it works. Your eyes scan every corner, every silent mannequin, treating the entire environment as hostile.

The game creates a powerful sense of paranoia where the threat is not just a monster, but the possibility of a monster. This initial feeling is a masterclass in psychological dread, turning the simple act of walking through a room into a tense negotiation. The narrative premise and the gameplay mechanic are in perfect sync.

But the illusion is fragile, and it breaks once you recognize the patterns. The terror of an unpredictable predator fades into the routine of evading a simple AI. You quickly learn its triggers, its line of sight, and the safe spots where it cannot reach you. The dynamic stealth of a game like Alien: Isolation, where the creature feels alive and adaptive, is absent here.

Instead, the gameplay loop calcifies into a low-stakes game of hide-and-seek. This is amplified by the focus on a single threat. The original FNAF games built pressure by forcing you to manage multiple dangers at once; it was about spinning plates. Here, you only have one plate to watch, and it wobbles in a very predictable rhythm.

The game attempts to inject excitement through heavily scripted chase sequences, but these moments often do more harm than good. Instead of being thrilling escapes, they feel like rigid trials where one misstep means instant failure.

Technical hitches, like your character getting caught on geometry or an enemy clipping through a wall, shatter the cinematic fantasy. When a chase sequence punishes you by sending you back to a checkpoint for a minor error, it ceases to be a source of tension and becomes a source of frustration. The fear of being caught is replaced by the annoyance of having to repeat the section.

This all points to a larger identity issue. The game is clearly trying to shed its reliance on the jump scares that defined the series. The scares themselves are telegraphed and lack the startling impact of their predecessors. Moving toward atmospheric horror is a respectable artistic choice.

The problem is that the game removes the old payoff without establishing a new one. The atmosphere builds a wonderful sense of dread, but it needs to lead somewhere. It sets a stage for a frightening performance that never quite begins. When a horror game builds and builds, but the final scare is little more than a loud noise, what is left to be afraid of?

Fighting the Game, Not the Monster

Beneath the stealth and horror lies the structure of a classic adventure game. Your progress through the manor is dictated by a handheld device, your key to unlocking doors of increasing security clearance. This system creates a clear, linear path forward, guiding you from one environmental puzzle to the next.

The challenges themselves are straightforward: find the right item, activate a sequence of machines, and open the next area. This loop of exploration and problem-solving is functional, but it’s the simple act of interacting with the world where the experience begins to fray. The game asks you to physically grab and pull levers with your mouse, an attempt at tactile immersion that many modern horror titles use.

When you have a quiet moment, this physical interaction can feel grounding, connecting you to the rusty, analog machinery of the world. The problems arise when the quiet ends. During a chase, when speed and precision are essential, wrestling with the controls to yank a door shut feels clumsy and unresponsive.

The immersive touch becomes a frustrating barrier. You are no longer fighting a monster; you are fighting the game’s interface. This kind of friction pulls you out of the horror and into a state of pure mechanical annoyance, a critical failure in the marriage of gameplay and emotional pacing.

This sense of fighting the systems is magnified by two core design choices. The inventory management is needlessly tedious. Instead of simply collecting an item, you must physically carry it to a designated “inventory chute.” This turns what should be a moment of discovery into a chore, forcing you to backtrack and break the flow of exploration.

Worse still is the unforgiving autosave system. Checkpoints are infrequent and poorly defined, meaning a single mistake during a long sequence can erase significant progress. This design does not create tension; it creates resentment. It disrespects the player’s time and effort, making sections of the game feel punishing rather than challenging. When the primary obstacles are tedious inventory trips and repeating entire sections, is the experience truly a horror game, or just a test of patience?

A Flawed Machine in a Perfect Shell

For all its mechanical frustrations, Secret of the Mimic is an absolute artistic achievement. The game’s presentation is immaculate, a testament to the power of atmosphere in interactive horror. Visually, it abandons the neon-drenched shopping mall of its predecessor for a grittier, more grounded “cassettepunk” aesthetic.

This is a world of analog decay, reminiscent of the lived-in, industrial dread of 70s sci-fi films. The lighting is superb, carving deep shadows out of dusty air and casting an unsettling glow from archaic CRT monitors. The costume designs themselves are wonderfully unnerving, turning familiar mascot shapes into uncanny, silent threats. The game simply looks incredible, offering a mature and refreshing visual direction for the series.

The soundscape is just as meticulously crafted. Audio is often the most potent tool in horror, and here it does much of the heavy lifting that the AI cannot. The distant, thunderous thud of metallic footsteps is a far more effective threat indicator than anything you see on screen.

Quiet moments are filled with the low, oppressive hum of dying machinery, ensuring the tension never fully dissipates. When a chase does begin, the music swells effectively, creating a cinematic sense of panic. The voice performances are a particular highlight, delivering emotionally resonant dialogue that injects a great deal of personality into the sparse narrative.

What is most surprising is the technical polish. After the notoriously rough launch of Security Breach, it is a genuine relief to experience a game from this studio that runs so well. The frame rate is a smooth and stable 60 FPS, with no noticeable stutters or crashes to break the immersion.

Load times are swift, and the entire package feels solid and well-built. This stability is critical because it isolates the game’s problems; the frustrations are a result of deliberate design, not technical failure. This raises a fascinating question: what happens when a game’s world is so beautifully and competently constructed, yet the act of playing within it feels so frequently clumsy?

More FNAF, For Better and For Worse

Secret of the Mimic presents a difficult proposition. It is a game of warring impulses: a gorgeously realized world with an incredible atmosphere, trapped in a body of clumsy mechanics and frustrating design choices.

The experience is a constant negotiation between appreciating its artistry and enduring its gameplay. For this reason, a recommendation comes with a heavy asterisk. This title is built almost exclusively for the established Five Nights at Freddy’s fan—the player who arrives for the deep lore and atmospheric storytelling. They will find just enough here to satisfy their hunger for a new chapter in the sprawling mythos.

For anyone else, especially those seeking a polished and genuinely frightening horror game, the purchase is much harder to justify. The $39.99 price feels steep for an experience whose core gameplay feels so frequently at odds with itself.

Newcomers will likely bounce off the unforgiving systems and the lack of impactful scares long before the credits roll. It is not an evolution of the formula or a bold new direction. It is, for better and for worse, simply more FNAF.

The Review

Five Nights at Freddy's: Secret of the Mimic

Five Nights at Freddy's: Secret of the Mimic is a gorgeous, atmospheric museum of a game that is unfortunately a chore to walk through. Its stunning visuals, masterful sound design, and intriguing lore are shackled to frustrating mechanics and a predictable threat. While the technical polish is commendable, the core experience feels more like a test of patience than a survival horror challenge. This is a beautifully crafted but hollow animatronic, recommended only for the most dedicated Fazbear faithful who value story over gameplay.

PROS

- Stunning audiovisual presentation and "cassettepunk" art direction.

- Excellent atmospheric world-building and environmental storytelling.

- Strong technical performance with a stable frame rate.

- Expands the series' lore in meaningful ways for fans.

CONS

- Frustrating and clunky core gameplay mechanics.

- Unforgiving autosave system and tedious inventory management.

- Predictable enemy AI diminishes the horror over time.

- Lacks genuine frights and relies on ineffective jump scares.