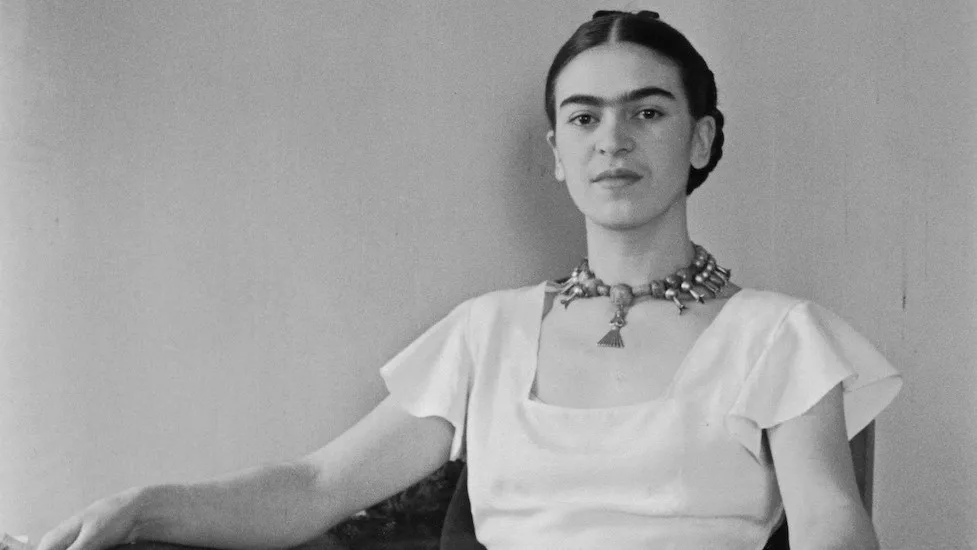

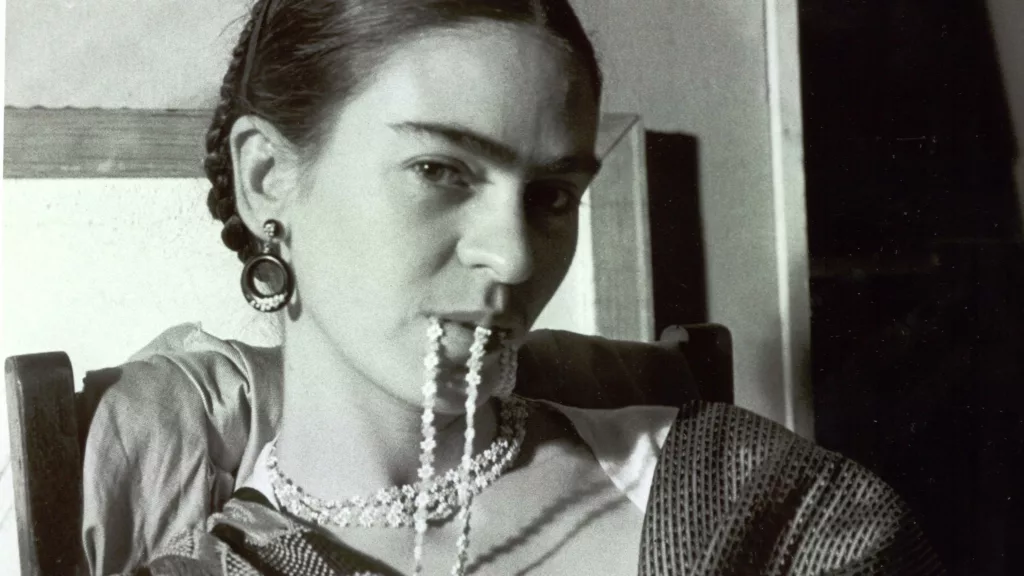

Even if you don’t know much about art, chances are you’ve seen Frida Kahlo’s face staring back at you. With her iconic unibrow and vibrant Mexican style, her image is everywhere – from t-shirts and tote bags to jewelry and home decor. But behind the commercialized icon is the story of a revolutionary artist and fiercely independent woman.

In the new documentary Frida, director Carla Gutierrez lets Kahlo tell her own story, using the artist’s diaries, letters, and interviews as narration. We follow her from inquisitive child to bohemian art student to tormented artist, exploring both her brilliant work and her tumultuous personal relationships. Alongside Kahlo’s narration, the film incorporates stunning photographs and footage from the time, interspersed with animated recreations of her surreal, psychologically-charged paintings.

It’s an intimate look at the real Frida – the progressive feminist just as focused on Mexican politics as messy love affairs. The film doesn’t shy away from the darker parts of her life, chronicling her miscarriages, infidelities, and the accident that left her disabled and in constant pain. Against all this, her art shines as a testament to her resilience and creative spirit. Full of color and defiance, Kahlo’s voice in Frida helps capture her uncompromising essence.

Kahlo In Her Own Words

Rather than speculate about the artist’s inner world, director Carla Gutierrez lets Kahlo speak for herself. The film’s screenplay consists almost entirely of text from the artist’s diaries, letters, and interviews. We hear intimate first-person narration as archival footage and photos immerse us in each era of her life.

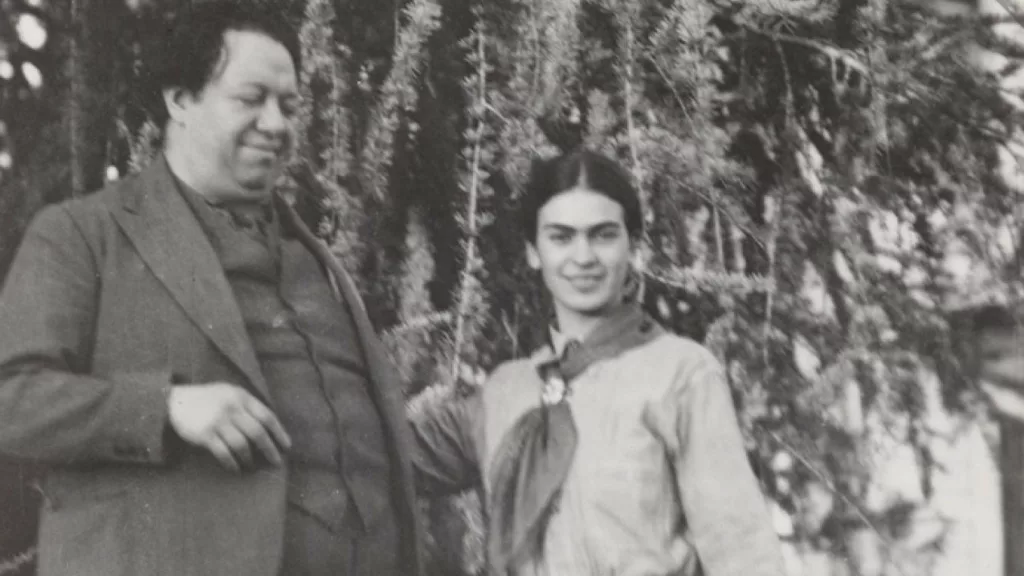

The approach makes the film feel raw—we dive straight into Frida’s singular perspective. When we first see her painting furiously in her studio, she explains frankly, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone.” Brief recreations of key scenes add color, showing her impassioned conversations with Diego Rivera or demonstrating her horrific accident. These dramatizations capture iconic moments without veering into full biopic territory.

Gutierrez incorporates Kahlo’s actual works with care, knowing their visual potency needs little enhancement. Animator Sofía Cázares adds subtle motion to the paintings, bringing small elements to life in sync with the emotions Kahlo describes. As she depicts her agony over Diego’s betrayals, tears stream down the face of her painting The Two Fridas. The effect is powerful yet delicate, hinting at the turmoil inside the stationary image.

By spotlighting not just the events of Kahlo’s life but her distinct way of processing them, Gutierrez uncovers the mind behind the icon. The film assembles a mosaic of primary materials—Kahlo’s diary scribblings, impassioned letters, brush strokes on canvas. Together they form an electrifying self-portrait of an artist firmly in control of her legacy.

“Step behind the curtain of a horror maestro with our Dario Argento: Panico review. Discover the genius and madness that fuel Dario Argento’s iconic films, as revealed in Simone Scafidi’s intimate documentary.”

Capturing An Unflinching Spirit

By using Kahlo’s candid writings as narration, the film conveys her perspective with striking intimacy. We get the artist’s emotions raw and unfiltered, from awed early dreams of being a doctor to painful isolation after her accident. Kahlo describes her complicated joy in marriage and motherhood, ecstasy found in affairs, and gnawing anguish when Rivera is unfaithful. Actor Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero performs the first-person voiceover, matching Kahlo’s fiery spirit. This candid approach transports us into the mind of the trailblazing icon.

Del Rivero’s passionate narration is bolstered by extensive research into Kahlo’s personality. Biographer interviews help round out her character, as close friends praise her infectious laugh and ribald sense of humor. The film also details her fierce political convictions, revolutionary spirit flowing from father’s radical politics and outrage at Rockefeller exploiting Mexican workers. We see her earthy charisma in real-life footage, chain-smoking with lust for life. Frida emerges not as untouchable legend but defiant, funny, sensual being.

The film archives brim with gems that truly place us within Kahlo’s world. We see her mischievous school photos, then watch her teenage self-portraits unfold. Footage from her husband Diego Rivera’s 50th birthday features a playfully eccentric Kahlo in action. These historical textures combine with animated paintings for vivid effect—when she discusses her New York trip we pan across archival images of 1930s NYC behind a colorful rendering of her painting. The layered visuals keep discovery fresh.

Far from the brooding saint of popular lore, this Frida celebrates earthly pleasures. We hear her views on free love straight from letters to Georgia O’Keeffe while seeing her flirt openly with women in old film reels. “I’ve always loved men and women alike,” she tells us breezily. Refreshingly matter-of-fact about her own bisexuality, she movingly describes the euphoria and anguish of her bond with Rivera. Del Rivero’s voice acting shifts fluidly between playful, sensual, wretched, matching the artist’s transparent range of emotions.

While animated paintings could easily distract, creative director Sofía Cázares adds movement judiciously. As Kahlo describes her late-term miscarriage, a section of her painting Henry Ford Hospital flows with blood. The effect is viscerally powerful yet focused only on elements central to her narrative. Likewise, animated tears fall to match Frida’s heartbroken voice. Rather than overtake Kahlo’s work, these sparse animations honor her candid spirit.

Where The Film Falls Short

The choice to follow a strict timeline from childhood to death, though clearly organized, feels predictable. Skipping through the decades season-by-season, we lose a chance to linger on formative periods. The film breezes by her teenage passion for politics and early painting days to land squarely on her courtship with Rivera. Shaped around their union and unraveling, the film never fully frees itself from Diego’s orbit. A more immersive structure could have traced aesthetic breakthroughs in her work, diving into specific canvases and the stories behind them.

A related drawback is the heavy focus on Kahlo’s infamously volatile marriage, at the expense of artistic development. Nearly a quarter of the runtime covers her ties to Rivera, glossing over her solitary painting practice. We witness Diego’s affairs and ensuing torment in detail, but see just brief interview clips on her creative process. While the relationship clearly impacted her art, more first-person footage on the works themselves would have better spotlighted her independent evolution.

A related drawback is the heavy focus on Kahlo’s infamously volatile marriage, at the expense of artistic development. Nearly a quarter of the runtime covers her ties to Rivera, glossing over her solitary painting practice. We witness Diego’s affairs and ensuing torment in detail, but see just brief interview clips on her creative process. While the relationship clearly impacted her art, more first-person footage on the works themselves would have better spotlighted her independent evolution.

Though used artfully in parts, some animated renderings of Kahlo’s paintings distract from her original compositions. Seeing flat portraits physically emote via digital tears and touches feels heavy-handed. Likewise, shuffling through a slideshow of paintings as Rivera espouses Communist values keeps the art itself at arm’s length when it could have been interwoven more purposefully. Allowing the unmodified works to stand alone, as powerful counterpoints to diary musings, may have carried greater emotive force.

With such a wealth of materials—vintage photographs, diary entries, brush strokes on canvas—stitching a unified mosaic proved understandably difficult. But the film struggles to connect the various narrative threads, feeling somewhat disjointed between candid voice recordings, archival montages, talking heads riffing on her legacy, and intermittent artwork animations. Moments of raw creative expression get lost between linear biographical bullet points, denying a truly immersive experience.

As an introduction to her work, Frida captivates. But it stops short of capturing the full force of her originality. We end without enough spotlight on the paintings themselves—how she blended Surrealist expressiveness with Mexican folk, how she evolved nature symbolism across decades, how her hybrid styles prefigured prominent mixed-media movements. The film succeeds as intimate personal portrait but misses the chance to cement Kahlo’s artistic contributions in viewers’ minds with a powerful concluding artistic arc. We’re left wanting more insight on her creative heights.

Examining The Artist And The Icon

The film showcases Kahlo’s subversive takes on gender and sexuality. We hear her blunt views firsthand, scoffing at the masses of dim-witted society ladies fawning over Diego. She confronts the engrained sexism even in her radical circles—as when the arrogant Surrealist André Breton patronizes her in Paris—with cutting intelligence. Her own cosmopolitan Mexican identity proudly flouts both American and European norms. The film emphasizes her affairs with high-profile women like Josephine Baker and vividly depicts her fluid, open-minded attitudes about love.

As a proudly Mexican artist embraced ultimately by the European elite, Kahlo inhabits multiple worlds while staying rooted adamantly in her heritage. She becomes incensed by the Rockefeller family commissioning Rivera’s work to whitewash their image, crying out against the oppression of workers. We hear her reflect on her mestiza background with nuance, describing both Aztec resilience and her father’s German-Mexican lineage equally vital to her personality. The multicultural complexity of her upbringing becomes crystalized in her hypnotic canvases, melding folk Catholic motifs with surreal dreamscapes.

The film returns often to the horrific trolley accident that left Kahlo’s body shattered yet catalyzed her creative talents. We learn painting initially helped her pass agonizing hours confined to bed in recovery. Later we hear her describe painting as emotional release—a mode of processing her turbulent interior world. As relationships and health deteriorate over years, she funnels this pain back into increasingly wrenching self-portraits. Works like The Broken Column visualize her spine’s severing with brutal intensity, fusing bodily trauma and psychic anguish. We see the solace art provided her even in suffering.

Beyond the slow-motion montages of Kahlo icon merchandise saturating gift shops, we glimpse the distance between the artist and the commodity. She describes feeling reduced by lavish museum exhibits like a “freak attraction” to high society patrons. As much as she courted fame, she chafed against misrepresentations like Breton’s. Yet later isolation offered its own miseries—her most tormented self-portraits come after separating from Diego, left alone with infirmity. We see her truest self not in the commercial myth but in private paintings made for herself, processing pain through perspective shifts and jolting self-analysis.

Kahlo As Guide To Her Own Legacy

At its best moments, Frida delivers raw proximity to an icon too often misrepresented. By ceding the story to Kahlo’s uncompromising voice, director Gutierrez captures her irresistible personality in all its unfiltered glory. We get the artist’s own irreverent musings, earthy humor, and poetic clarity. The film brings her diverse relationships and sexuality to life with intimacy and nuance. Painstakingly assembled photographs, diary pages, and footage form vivid collage, steeping us in the worlds she inhabited.

If the linear storyline flattens her progression somewhat, we still gather gripping firsthand texture of this radical spirit. And the sparing yet evocative animated paintings enhance the film’s emotive peaks without overwhelming Kahlo’s originals. While it may leave lingering questions on her innovative stylistic arcs, Frida succeeds mightily as an introduction, an invitation to Kahlo’s essence. It inspires further journeying into her aesthetic evolution across those indelible self-portraits with their haunted psychological intensity.

We emerge hungry to witness more fully the artistic milestones only glimpsed here. If the film falters in tying biographical threads into tidy summation, it delivers something more vital: direct channel into the mind firing those latent symbols onto canvas. We get storyteller Kahlo in robust form, teasing out threads of her own mythology with characteristic candor, wit, and flinty grace. It’s a portal well worth entering.

The Review

Frida

Frida brings Mexico’s storied painter to life largely on her own incisively poetic terms. With Kahlo’s candid writings guiding us through formative events, director Gutierrez crafts an electrifyingly immediate portrait. If an overly linear structure and overemphasis on Diego Rivera sometimes muffle the film’s momentum, we’re still left marveling at the wealth of archival treasures unveiled. Moments spotlighting Kahlo’s creative process prove enthralling, even if her full artistic impact remains hazy. What resonates most is the unfiltered, complex, defiantly human artist who emerges under the icon's veil. By centering Kahlo’s perspective, the film captures her spirit with contagious verve and hard-won honesty. Frida compellingly channels a revolutionary voice.

PROS

- Raw, candid first-person narrative from Kahlo's writings

- Strong voice acting brings her bold spirit to life

- Conveys complexity of relationships and sexuality

- Wealth of well-integrated archival materials

- Some subtle yet powerful animated painting elements

CONS

- Conventional linear structure feels overly familiar

- Overly Diego Rivera-centric at times

- Some heavy-handed animated renderings of paintings

- Unable to fully unify biographical threads

- Lacks emphasis on artistic legacy and impact