Back before climate change became such a polarized issue, the stakes were already high. Growing up in the 1970s, concern about our warming world started gaining attention. People saw signs of record heat waves and natural disasters. Leaders like President Carter sounded warnings too, urging America to cut wasteful habits as scientists’ grim forecasts grew louder. Most seemed willing to make sacrifices then.

But changing times and tensions brought change as well. The gas crisis shook things up, and new voices rose that downplayed dangers. By 1988, temperatures were still climbing, yet few could’ve predicted what the next few years held in store climate-wise—or politically. That’s where The White House Effect shines a light, taking us back to a pivotal period soon forgotten.

The film focuses on a single presidential term, but one that could have put us on a whole different path. Back when both sides openly acknowledged global warming, George H.W. Bush struck an unusual tone. As vice president, he vowed the highest office would triumph over this “Greenhouse Effect.” Becoming president, he appointed America’s first environmentalist to the EPA. Here was a chance, maybe, to forge global action before it was too late.

Of course, as the documentary reveals, powerful forces had other ideas. Pressure was mounting from allies with deep fossil fuel ties. Changing tides soon led leadership astray from initial goodwill. Opportunities slipped by as science faced resistance. Through it all, one thing remains clear: back then, with problems less severe, we already possessed the means to steer safely through this turbulence. This film brings that fleeting moment vividly to light once more.

Getting Warm

The story of climate change starts getting hot in the 1970s. That’s when our warming world started bubbling up into the national conversation. People were witnessing some odd signs—virtual heat waves blistering across the country with alarming frequency. Meanwhile, scientists kept sounding increasingly urgent warnings about the impacts of all the carbon we were dumping into the skies.

Jimmy Carter took those warnings seriously as president. Back in 1977, his administration published a report predicting catastrophic consequences if emissions weren’t curbed. Carter addressed the nation directly on television, imploring Americans to tighten their belts by making sacrifices like solar power and fuel efficiency. Many responded positively to his call for collective action.

However, momentum slowed when the energy crisis hit in 1979. With oil supplies constrained and fuel prices skyrocketing, anger was directed at Washington. Carter’s political capital was badly depleted. His defeat in 1980 opened the door for Ronald Reagan’s pro-business, anti-regulation approach. The Gipper promptly set about unraveling many of the environmental laws and alternative energy investments established in the Carter years.

By the late 80s, the effects of all this carbon were becoming undeniable. The hottest summers on record were scorching the country right as another election loomed. No doubt the weather contributed to George H.W. Bush’s vow, as vice president, that climate change would be no match for “The White House Effect.” How little did he realize back then the challenges his presidency would face on this front in the years to come? Scientists knew the causes and impacts, even if the politicians remained largely unaware of what turbulence lay ahead.

Promises and Perils

By 1988, the issue of climate change had well and truly arrived. That year, people across the country baked under some of the hottest weather yet recorded. As temperatures rose, so too did calls for leadership on this growing threat.

That’s where George H.W. Bush came in. During his campaign for the vice presidency, Bush spoke at a rally about making good on “the greenhouse effect.” With confidence, he declared the powers of the Oval Office were mighty—this problem would be no match for “The White House Effect” if he assumed that role.

So when Bush was elected president later that year, many held hope his White House really could drive change. Right off the bat, he appointed signs pointed in the right direction. William Reilly, a lifelong environmental advocate, took charge of the EPA. Reilly dove into the challenge with gusto, seeking global deals to curb emissions.

However, not all in Bush’s inner circle shared this urgency. As Chief of Staff, John Sununu saw things differently. Where Reilly’s focus centered on climate science, Sununu emphasized economics above all else. With industry giants in his ear, he seemed determined to keep this issue on the backburner.

The diverging visions of these two key advisors hinted this administration’s stance might not stay so straightforward. While Bush’s speech spurred initial optimism, troubles lay ahead if he couldn’t align all parts of his team behind the pressing mission of climate action. Little did anyone realize how Sununu’s resistance would transform their work—and alter history’s course.

The Clash for the Climate

Big changes were coming from D.C. on the environmental front. With Reilly leading the EPA, the new administration got off to a running start. He dove headfirst into diplomatic rounds, aiming to build an international wall of treaties against rising emissions.

But Reilly’s strides were about to hit a massive roadblock—the man named John Sununu. As Bush’s Chief of Staff, Sununu wielded major control over what issues crossed the president’s desk. And on climate, his views couldn’t have been further from Reilly’s.

While Reilly sounded alarms about the state of our warming world, Sununu saw things quite differently. Through close ties with fossil fuel tycoons, he focused solely on profits. Any motion on climate-regulating industry was deemed “anti-growth” in Sununu’s eyes.

From then on, Reilly’s job got exponentially harder. Sununu made sure greenhouse gas cuts stayed buried under other concerns. He restricted which experts had the president’s ear, favoring those who downplayed threats. Time and again, Reilly found his climate pleas stifled before ever reaching Bush.

As the influence battle tipped in Sununu’s favor, Bush’s attitude unwinds. The firebrand enthusiasm of his campaign was getting drowned out by more muted messaging. Agreements Reilly negotiated abroad met deaf ears back home under Sununu’s blockade.

By the time Sununu left, years of whispered denials in Bush’s ear had taken their toll. What was once a bipartisan issue transformed into something entirely—the first volley in a war on climate action still raging today. All because one man’s priorities eclipsed all others in the White House.

Sowing Seeds of Doubt

With Reilly confined by Sununu’s resistance, the fossil fuel gang helped themselves to the opening. You see them worming into places they didn’t belong—like television, supposedly for “balance.” Except their message wasn’t guided by science; it was scripted for skepticism.

Doubt may have been their game, but real threats kept materializing. No matter how media mercenaries spun blame elsewhere, Americans watched crises unfold from Exxon’s spilled sludge to record hurricanes. Yet their voices only grew louder, declaring none of it proved. The “is it happening or not?” antics drowned out the deeper discussion.

Not that the White House helped that discussion. When international climate work began in earnest abroad, America was MIA. Bush blew hot air about global leadership while Sununu ensured his failures to deliver. Reilly played cheerleader for empty gestures at home. And the ozone healed as greenhouse gases only swelled higher.

By 1992, Bush shed any pretense of progress for good. At the Earth Summit, a lonely Reilly weakly defended America under Sununu’s shadow. His successor would peddle “voluntary” pledges as a global partner exited stage right. The issues Bush vowed to solve were redefined by others as matters “open to debate.” From there, the die was cast for generations to come.

Chances Not Taken

As the closing scenes make clear, many look back with deep regret over chances missed. In later interviews, Reilly and renowned climate expert Stephen Schneider acknowledge opportunities squandered when action stood the best chance.

Their feelings echo the assessment of Al Gore. As far back as 1984, he noted the issue shifting from science into politically charged terrain. The White House Effect depicts this pivot point in stark terms.

Sobering graphs illustrate the change wrought. A chart depicts CO2 levels since prehistory as virtually flatlined—until the Industrial Revolution lit the fuse. Concentrations exploded when oil and coal powered empires and economies. Corresponding temperature records leave little doubt about the heating planet.

Most troubling is imagining how else things might have unfolded. With both sides initially willing to curb emissions, a bipartisan drive for global cooperation seemed attainable back when impacts weren’t as extreme. Had leadership seized that fleeting chance, who knows how much greater resiliency might exist to face today’s escalating climate pressures?

Instead, short-term priorities and fossil-funded voices of doubt squandered what was likely humanity’s best shot at avoiding the climate chaos now unfolding. The film is inspired by the leaders who tried, yet mostly leaves viewers mourning a pivotal period and chances that slipped through our grasp.

A Moment Lost in Time

As The White House Effect draws to a close, it leaves you with a bittersweet feeling. On one hand, the film shines a light on an important crisis too long forgotten. But seeing how close we came to facing climate change united—only to fall so far—leaves a strange sense of mourning for what might have been.

This look back at Earth’s tipping point underscores how one pivotal moment was squandered when bold action stood the best chance. Early ambition gave way to denial as moneyed interests held sway. And partisan polarization converted an issue of science into one of polarized politics.

While the documentary offers compelling clues, it can only delve so deep with archival sources alone. Viewers are left craving more context on how key relationships soured and why resistance took root. But one thing comes through clearly—a mere few influences altered humanity’s entire trajectory.

With impacts escalating more rapidly than anticipated, the timeliness of revisiting our missed opportunity couldn’t be greater. This film ensures one era’s failings and fossil-fueled duplicity aren’t forgotten. Its alarming relevance makes the historic crossroads of 1989-1993 more than a political post-mortem—but an urgent call to safeguard the future while we still can.

The Review

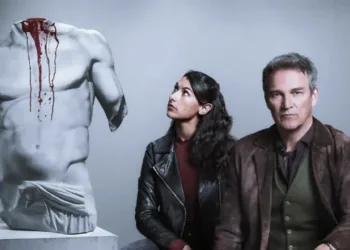

The White House Effect

The White House Effect sheds invaluable light on a pivotal climate moment too long forgotten, even if it leaves some stones unturned. While raising more questions than it answers at times, the documentary accomplishes its aim to bring this consequential period vividly to life. Overall, the film makes a strong case that even decades ago momentum could have propelled us towards safer climate outcomes had short-term priorities not gotten in the way.

PROS

- Illuminating examination of a forgotten period of climate policy history

- Masterful use of archival footage to transport viewers back in time

- Provides compelling clues about how messaging shifted on this issue.

- Underscores the fragility of early opportunities for bolder climate action

CONS

- Leaves some important context and motivations less thoroughly explained.

- Bounces around timeline in a way that can feel disjointed at times.

- Overly reliant on archives limits depth of analysis possible.

- Doesn't provide a fully formed thesis for why momentum was lost.