As Pakistan’s first hand-drawn animated picture, “The Glassworker” emerges as a revolutionary piece of cinematic history. This film, directed by the multi-talented Usman Riaz and produced by Mano Animation Studios, is more than just a movie; it is a cultural statement that combines traditional storytelling with modern animation methods.

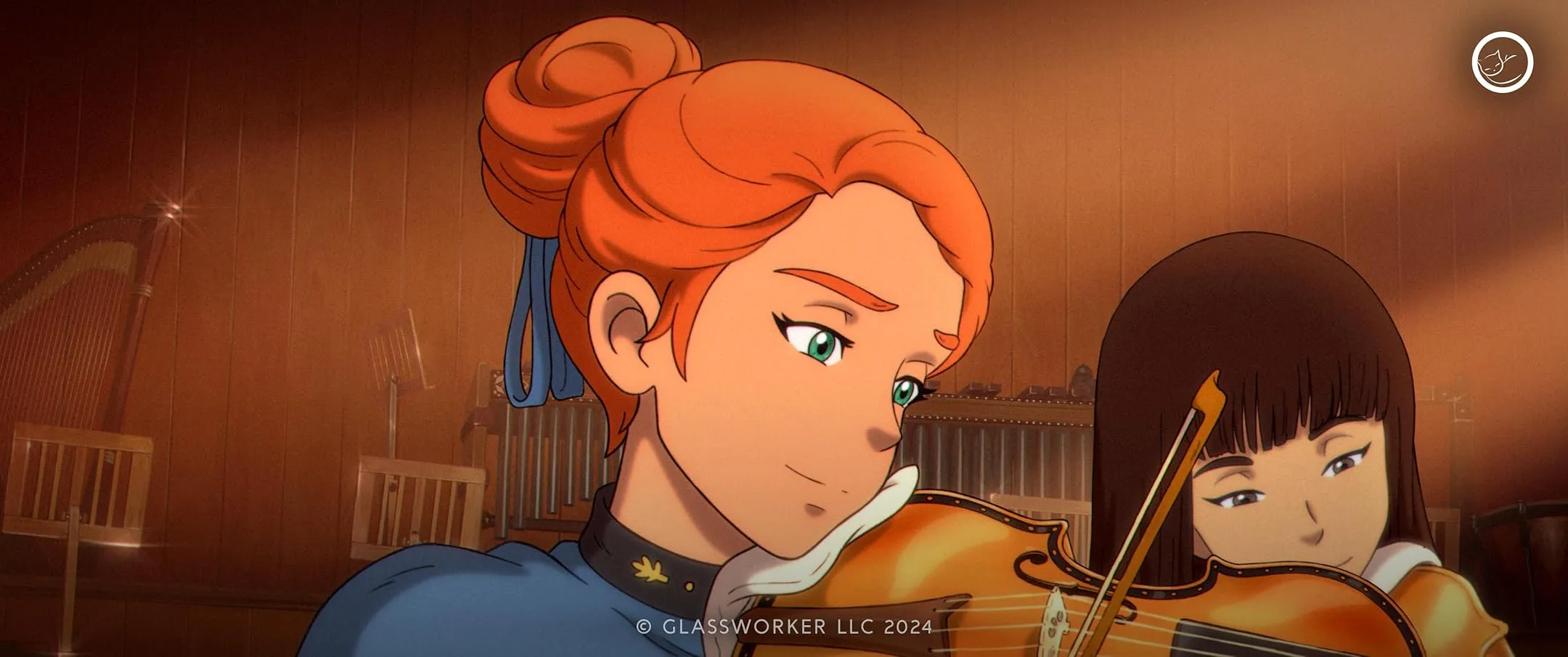

Deeply influenced by the famed Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki’s iconic works, “The Glassworker” goes beyond mere mimicry. The film tells a complicated story set in a steampunk-inspired universe, exploring themes of art, war, and human resilience through the eyes of Vincent, a teenage glassblower, and Alliz, a gifted violinist.

Riaz’s debut movie has already received international attention, with premieres at festivals such as Annecy and Cannes. This achievement is particularly significant since it highlights Pakistan’s burgeoning animation skill and introduces worldwide viewers to a distinct cultural perspective.

More than just an animated film, “The Glassworker” expresses artistic possibility passionately. Riaz and his team created visual poetry on the transformative power of creativity in the face of violence by combining elements of Pakistani culture, magical realism, and a deeply humanist narrative.

The film exemplifies the founders’ vision and determination, as they actually built an animation studio from the bottom up to accomplish their artistic ideals. It’s a wonderful voyage of passion, skill, and cultural storytelling that has the potential to expand Pakistani animation’s global reach.

Glass, Music, and Shadows of Conflict

In the lovely realm of Waterfront Town, where Dutch Renaissance architecture meets South Asian sensibilities, a beautiful story emerges. Consider a setting where exquisite buildings stand against a backdrop of looming war, steam-powered airships float overhead, and the delicate art of glassblowing coexists with military tensions.

Vincent Oliver’s livelihood centers around his family’s glassworks, passed down through the generations. As a young apprentice, he is determined to perfect the complicated skill under his father Tomas’ strict but caring supervision. Everything changes when Colonel Amano’s daughter, Alliz, arrives in town. She’s a violin prodigy, and their bond is instant—two artists finding common ground in a world increasingly fraught with strife.

The brewing war takes on an intangible form, gradually altering everything it touches. Vincent’s pacifist father is reluctantly lured to making glass components for military equipment, a moral compromise that weighs heavily on the family. Meanwhile, Vincent and Alliz balance their burgeoning emotions against escalating nationalism and military coercion.

Mysterious supernatural aspects, such as whispers from local djinn that reflect and refract light, provide an ethereal dimension to Vincent’s adventure. These unseen beings appear to direct and mold his course, lending a touch of magical realism to the story.

As time passes, the war erodes the town’s innocence. Vincent develops from an idealistic adolescent to a more sophisticated, bitter adult. His artwork becomes a symbol of lost dreams and resilience, reflecting the subtle emotional scars caused by battle.

The story is about more than simply love and war; it’s about how art becomes a sort of survival—a method to keep humanity alive when the world appears to be destroying it. “The Glassworker” examines how creation may serve as both a shelter and a form of resistance to the destructive forces of nationalism and militarism via the experiences of Vincent and Alliz.

Souls of Glass and Melody

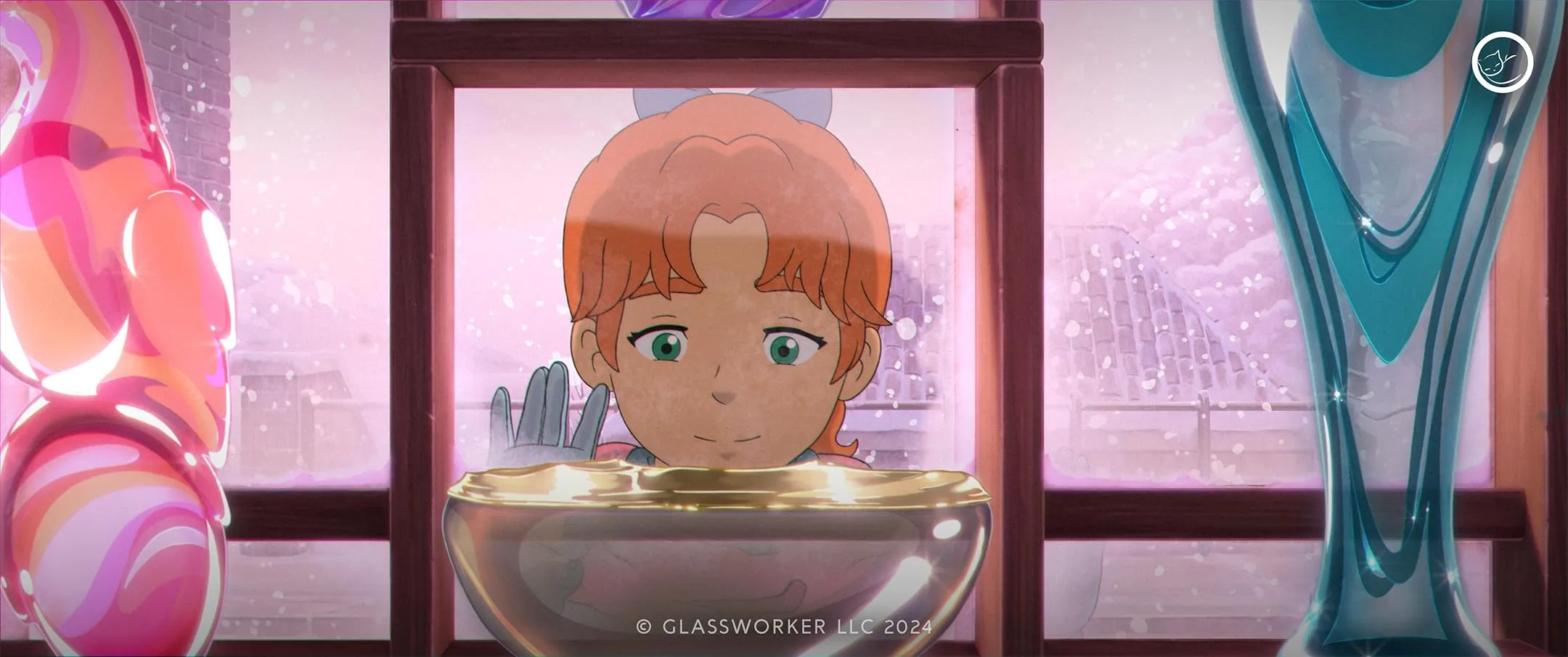

Vincent Oliver emerges as a complicated character, his life engraved as delicately as the glass he makes. Beginning as a wide-eyed apprentice under his father’s careful supervision, Vincent grows from an idealistic teenager to a contemplative artist with emotional scars from battle. His journey is distinguished by an unyielding dedication to his profession, a rebellious personality, and a deep-seated pacifism passed down from his father.

Alliz is the ideal counterpoint to Vincent—a military daughter with musical ambitions caught between parental expectations and personal goals. Her character represents the struggle between interpretation and creation, frequently questioned by Vincent’s rigorous concept of artistry. She navigates a society in which her identity is dictated by her father’s military standing, despite her desire for something more significant.

Tomas Oliver serves as the narrative’s moral compass. He is a widowed glassblower who opposes war on principle and embodies silent rebellion. His determination to teach Vincent the delicate art of glassblowing is a metaphor for humanity’s survival in the face of catastrophic powers. When pressed to support the military’s glass standards, Tomas’ internal conflict becomes a poignant statement on personal ethics.

Colonel Amano acts as the narrative’s militaristic balance. He is more of a complicated portrayal of systemic violence than a villain, embodying the conflict mechanism. His encounters with Tomas demonstrate the inherent conflict between artistic creativity and military destruction.

These individuals are more than just characters in a story; they are examples of greater philosophical disputes. Through their intertwined adventures, “The Glassworker” investigates how personal choices are passed down through generations, how art can defy injustice, and how individual humanity persists in the face of societal cruelty.

Their relationships go beyond conventional sexual or familial ties, becoming a sophisticated examination of how people maintain dignity and creativity under difficult circumstances.

Crafting Worlds Between Glass and Imagination

“The Glassworker” symbolizes a dramatic visual revolution in Pakistani animation. Each frame is painstakingly hand-drawn, and each image is infused with the kind of impassioned detail that elevates animation from basic movement to living art.

The film’s visual language says volumes, combining Studio Ghibli’s ethereal sensibilities with a distinct Pakistani aesthetic. Imagine a world where Dutch Renaissance architecture coexists with South Asian cultural nuances and steam-powered zeppelins soar above streets filled with characters dressed in Western and traditional Muslim garb. This is not just animation; it is cultural geography.

The vibrant color palette captures Waterfront Town’s complex emotional terrain. As war approaches, soft, subdued tones shift radically to more vivid, shattered color schemes. Glass becomes more than just a material; it’s a metaphorical lens through which the story reflects on human existence.

Supernatural themes flow smoothly throughout the story, with unseen djinn symbolized by light’s captivating dance. Carmine Di Florio’s score softly complements these ethereal presences, producing a sense of magical undertones that are both old and contemporary.

Steampunk aesthetics make an excellent backdrop, with elaborate machinery and antiquated technology acting as more than just site dressing. These components become compelling emblems of human innovation’s ability for both creation and devastation.

The animation’s most astounding feat is its sophisticated character expression. Without saying a word, subtle details such as a slight wrinkle beneath Vincent’s eye and the way light strikes Alliz’s violin express volumes.

This is not just an animation. It’s a visual symphony that defies traditional storytelling while preserving the rich traditions of global animated cinema.

Echoes of Resilience: Beyond Battlefields

“The Glassworker” converts war from a distant political abstraction to a personal human experience. The story doesn’t merely criticize conflict; it also examines how violence penetrates human dreams, corroding them like acid on fragile glass.

Art emerges as the ultimate form of rebellion. Vincent’s glassblowing and Alliz’s music become more than just artistic expressions; they are subtle means of resistance to a world that seeks to crush the individual soul. Each meticulously created piece signifies defiance—a steadfast will to see beauty amid disaster.

The love story between Vincent and Alliz defies romantic clichés. Their bond signifies something more profound: two souls recognizing their mutual fragility in a chaotic world. Their relationship is more than just romantic attraction; it is also about a shared awareness of how external circumstances can alter human trajectory.

Resilience flows through the story like an underground current. Characters don’t just survive; they transform. Vincent’s progressive emotional transformation from a naïve apprentice to a complicated adult reflects greater societal developments. His wrinkles and weighted expressions convey stories that words cannot portray.

The supernatural plotline involving the djinn provides an extra layer of metaphysical resistance. These unseen beings imply that hope exists beyond immediate physical realities—a potent reminder that imagination may overcome institutional cruelty.

Finally, “The Glassworker” contends that tiny, consistent acts of innovation and compassion determine human dignity rather than great actions. These characters chose to rebuild in a world ripe for destruction, one delicate moment at a time.

Pioneering Pixels: Crafting Cultural Cinema

Usman Riaz emerges as a cultural architect altering Pakistan’s artistic scene, rather than merely a director. His debut feature marks a watershed moment, bringing hand-drawn animation from a distant fantasy to a practical reality. With a glassblower’s accuracy and a storyteller’s imagination, Riaz creates a narrative that brings each precisely sketched frame to life.

Mano Animation Studios wasn’t just making a film; they established a complete ecology of artistic possibility. Under Geoffrey Wexler’s mentorship—a link to the famous Studio Ghibli—the crew turned limits into opportunities. Each challenge became an opportunity to create, and each impediment a possibility for a creative breakthrough.

The production’s most noteworthy achievement is its narrative approach. Riaz uses childhood flashbacks not as a gimmick but as a powerful storytelling method. These memories unfold like fragile, intricate glass sculptures, carrying deep emotional weight. The pacing is meticulous, allowing moments to breathe and reverberate before building to emotionally powerful disclosures that feel both unexpected and unavoidable.

International recognition at festivals such as Annecy was more than just an accomplishment; it was a declaration. “The Glassworker” proved that Pakistani animation could compete with worldwide counterparts, challenging accepted beliefs about cultural storytelling.

Riaz’s technique goes beyond traditional filmmaking. He’s not just presenting a story; he’s conserving a cultural memory and investigating how art survives in a world that appears determined to destroy it. Each picture becomes a monument to human tenacity, and each scene is a brushstroke in a bigger story of hope.

Transformative Visions: Beyond Borders

“The Glassworker” emerges as more than just an animated film; it is a cultural landmark pushing Pakistani filmmaking’s boundaries. Usman Riaz and Mano Animation Studios have created a piece that goes across national boundaries, expressing a common language of artistic perseverance.

The film’s genuine brilliance comes from its delicate balance of human tale and broader social reflection. Every frame is charged with purpose, transforming what could have been a straightforward war story into a sophisticated examination of human ingenuity under pressure. Vincent’s journey becomes a metaphor for artistic survival, with glassblowing functioning as a potent symbol of human fragility and fortitude.

Technically, the animation represents a quantum leap in Pakistani cinema. While there are few instances of narrative unevenness, the visual storytelling generally outweighs any slight structural flaws. The supernatural elements, notably djinn, lend layers of mystical richness to the storytelling, elevating it above traditional animated narratives.

Studio Ghibli’s influence is undeniable, yet “The Glassworker” refuses to be a mere replica. Instead, it has a particular voice—part Pakistani, part international, and wholly captivating. The film reveals that emotional authenticity, rather than technical perfection, defines excellent animation.

“The Glassworker” is a must-see for animation fans, cultural explorers, and anybody who believes in the transformational power of art. It promises more than simply a movie—it promises an experience that will change the way we think about storytelling, war, and human perseverance.

This is not only Pakistan’s first hand-drawn animated film but also a declaration that imagination has no boundaries.

The Review

The Glassworker

"The Glassworker" is a stunning debut that crosses cultural and creative borders. Usman Riaz has created a captivating animated film that effectively discusses art, resistance, and hope. By combining Pakistani local idiosyncrasies with global storytelling, the film provides a poignant reflection on human perseverance in the face of conflict. Its hand-drawn animation, heavily influenced by Studio Ghibli yet completely original, is a watershed moment for Pakistani cinema. The film's merits include its multifaceted characters, outstanding visual storytelling, and subtle examination of art as a means of resistance. While the narrative pacing can sometimes be inconsistent, "The Glassworker" makes up for it with emotional depth and visual poetry. This cultural statement challenges perceptions and celebrates the transformational power of art, not just an animated movie.

PROS

- Stunning hand-drawn animation

- Unique cultural perspective blending Pakistani and European influences

- Powerful anti-war narrative

- Remarkable visual storytelling

- Complex character development

CONS

- Occasional narrative pacing issues

- Some supernatural elements might feel slightly disjointed

- Complex themes might challenge younger viewers