The film Snow Leopard shows a farmer who traps a snow leopard after it kills his sheep, creating a conflict about survival and morality. His monk brother, Nyima, asks him to free the leopard, seeing it as sacred, as government officials and a TV crew come to the scene with their separate aims.

The film takes place on cold Tibetan lands in Qinghai province, where empty landscapes show the clash between desperate humans and nature’s cold response. The story mixes revenge, faith, and power in a measured story asking how people live with natural forces they cannot manage.

Pema Tseden made Snow Leopard as his last film before dying at 53. He made films showing Tibetan life with deep observation, looking at Tibetan people living under Chinese control. This work brings up big life questions and seems like a quiet look at life, death, and what lies between.

Predator and Prey: The Fragile Balance Between Man and Nature

Jinpa rages with raw force, screaming at a world blind to his pain. His nine sheep, killed at night by a snow leopard, meant food and money for his family’s basic needs. The leopard’s attack shattered his way of life and his pride. He puts the animal in a cage and says he’ll kill it if no one pays him back – fighting against both nature and officials who make empty promises.

Jinpa’s anger shows what many rural farmers feel, stuck between old problems and new rules. They can’t use guns to guard their animals, and money from the government comes late or never. He shows how people feel toward protected wild animals they can’t stop. His anger makes sense, yet it takes over his mind, making him as stuck as the leopard in its cage.

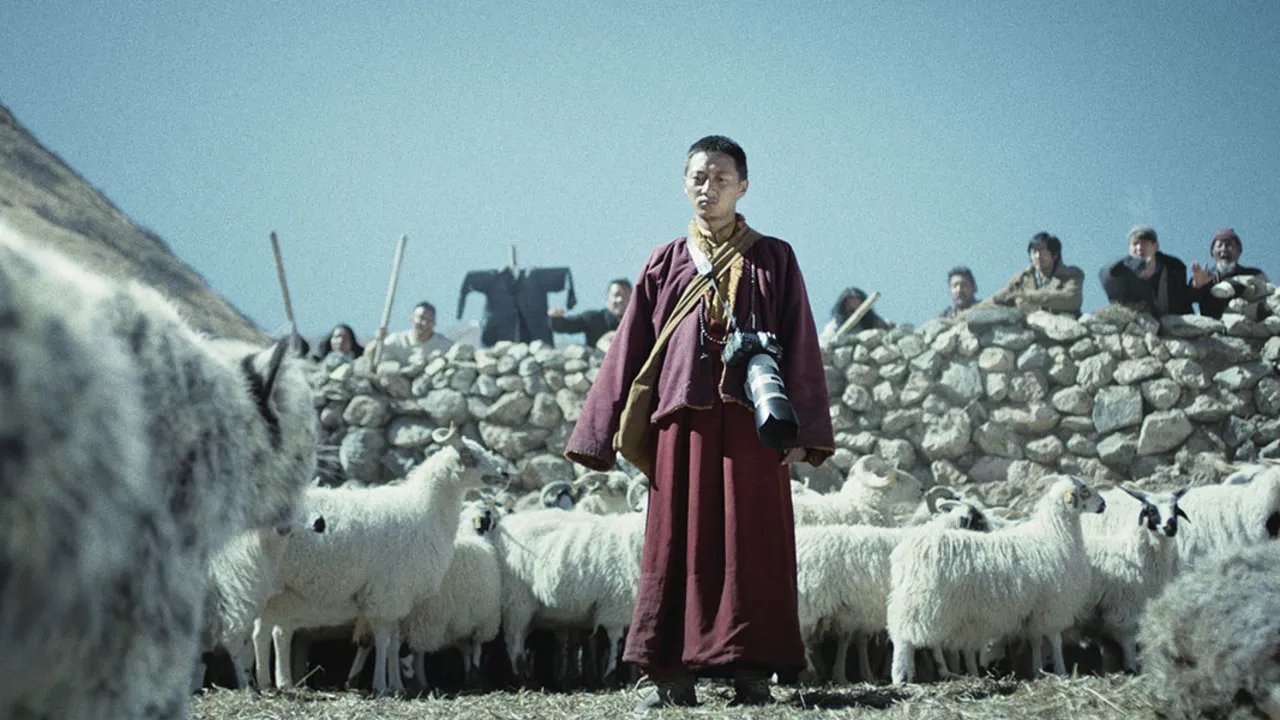

His brother Nyima sees things differently – he looks at the snow leopard with wonder. People call him the “Snow Leopard Monk.” To him, the animal brings holy messages and shows nature’s rules. He thinks the leopard lives beyond good or bad, part of a natural system humans left behind.

Nyima wants peace. He believes animals and humans link together in life’s big picture. Still, his ideas have odd spots. He takes photos of the leopard in amazement, wanting to keep its picture like others might want to keep the real thing.

The fight between Jinpa and Nyima goes past being just brothers mad at each other. It shows how humans try to stay alive while doing what’s right for other living things. The caged snow leopard sits there, pulled into a fight it knows nothing about.

The movie stays away from simple fixes. The brothers’ fight meets government workers’ cold rules and TV people watching from far away, making a scene full of problems with no clear end.

Threads of Rage and Reverence: Exploring Character and Symbol

Jinpa burns with steady rage from living on life’s edge. His sheep, killed by the snow leopard, meant staying out of poverty. He shouts his pain to a deaf world. The government’s empty promises to pay him back and laws that guard wild animals leave people like him with nothing, eating away at his self-worth.

Something soft stays inside his anger. Jinpa fights hard from care – for his kids, his home, the life he sees slipping away. He’s no bad guy, just someone trying to keep his place in a world that pushes him down. People see themselves in his fight, like many country folk left to face big things they can’t beat.

His little brother Nyima stands different, calm against Jinpa’s storm. Being a monk, he sees the snow leopard through holy eyes. To him, the big cat isn’t bad or scary – it just is. He looks at life softly, like someone who accepts that nature does what it wants.

Still, Nyima isn’t simple. His strange meetings with the leopard – half dream, half real – show he can’t let it go. He takes photos trying to steal some of its magic. His holy ideas mix with plain human wants, just like his brother’s.

Their father stays in the middle, asking both sons to wait and give a little. He brings old knowledge, but loud voices talk over him.

The TV people and bosses watch from far away, making things worse while saying they help. They turn real hurt into TV shows and paperwork, feeding it to people who’ll never know what it means.

The snow leopard stays wild yet stuck, showing what the movie means. It does what nature does – pretty and mean, not caring what humans think is right. Jinpa sees it wreck his life. Nyima calls it holy. The cat shows what people put on it – hate, love, fear, and wonder. It’s no hero or bad guy, just proof that nature runs its own way, blind to what humans want.

A World Seen and Unseen: The Visual Language of “Snow Leopard”

The camera work on the Tibetan plateau makes it look empty and cold. The big screen fills with long shots of open space that goes on forever. The mountains covered in snow and bare land show what the movie says: tiny people next to big, uncaring nature.

People’s small lives play out here – a mad farmer, a quiet monk, a troubled family. Their fights look tiny next to the still mountains, like the land doesn’t see their pain.

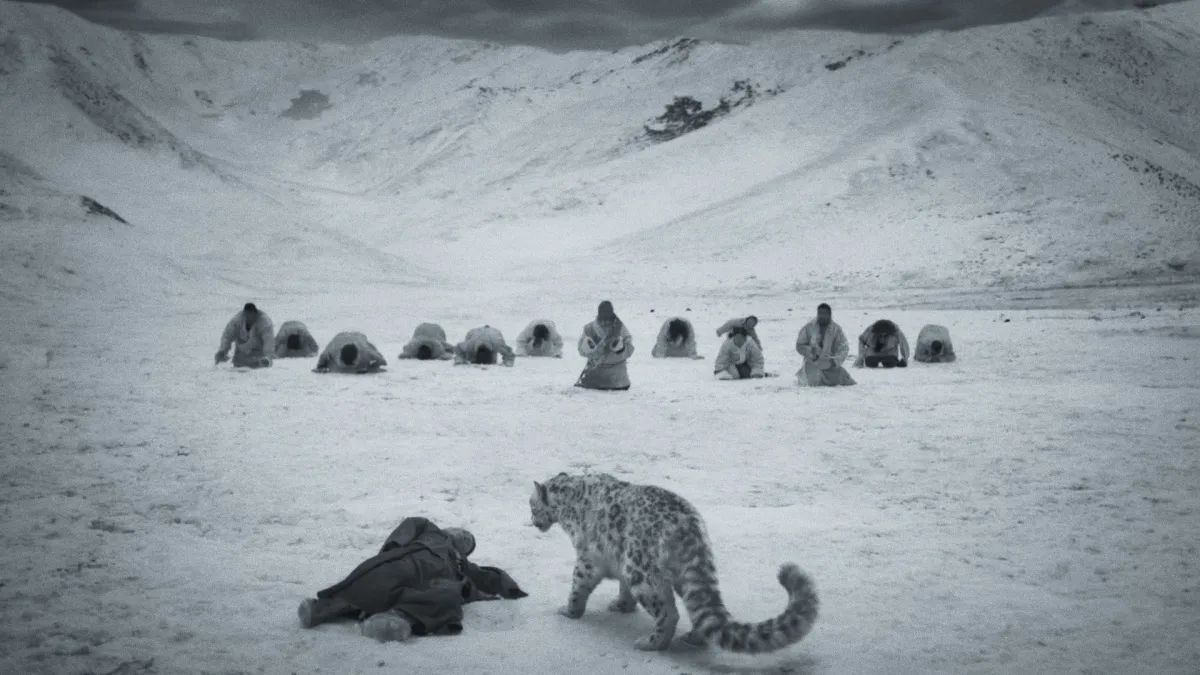

The black and white dream parts look different from the real parts. These odd bits mix what people think happened, what they made up, and what they feel deeply. Nyima and the snow leopard float in a weird space where talking stops and only raw links stay. The black and white makes everything simple: just the monk trying to know the big cat that stares back, saying nothing. These parts feel like dreams, pulling viewers into the monk’s deep link with the wild animal.

The rest of Snow Leopard looks real, like news footage. The camera shakes and runs long without stopping, making you feel like you’re there. This works best when we see through the TV team’s lens, showing how cold they are about people’s real pain. They look for good pictures while real hurt happens below their cameras.

The Leopard’s Gaze: Philosophy and Spirit in Conflict

The monk meets the leopard in dreams where real life mixes with magic. These black-and-white scenes show a space where people and animals share minds. The scenes match what Nyima believes – that all living things link together. The big cat stops being scary and shows the monk’s wish for peace during fights.

These strange meetings feel like small voices telling us about old rules we forgot, about how nature works without caring what humans want.

The movie asks if we should save the big cat or the farmer’s work. Jinpa’s anger makes sense – his sheep keep him fed, and the rules that save the leopard leave him alone with nothing. Nyima wants both sides to live together and says the cat should stay alive just like the sheep. Nobody gets a clear answer, and we must think about what’s fair, who loses, and how people stay alive.

Snow Leopard shows fights between what bodies want and what souls need, between breaking things and loving them, between people ruling or letting go.

Jinpa tries to make wild things listen to him, like all people do. Nyima stays quiet and thinks the leopard brings holy messages. The movie makes us think: Can people live with wild things they tried to beat? Maybe we’re stuck doing what the leopard does – just trying to stay alive.

Lines of Power and Disconnection: Social and Political Undercurrents

The movie shows bosses and police who seem far away and stiff. They show up saying rules and making promises that don’t help Jinpa’s real problems.

They act like their papers and rules, which sound good but don’t work when real people need help. Their empty words make Jinpa see how little he can do, and their promises to pay him back float away like the wind on the hills. The big shots can’t fix things, and the farmer fights alone to stay alive.

The movie asks hard things: What do we do when saving animals hurts people? Some rules try to keep wild things safe but forget about country people who lose food and money. Jinpa screams for people like him, who nobody sees when they talk about animals and people living next to each other.

The snow leopard stays safe with all these laws, but the humans it hurts get nothing. This looks like what happens everywhere – poor people get pushed aside by green rules made by rich city folks.

The movie says small things about being Tibetan under Chinese rules. People see the leopard two ways – holy to Tibetans, but tied up in Chinese laws. The movie speaks best when it stays quiet – when trying to live meets losing your say, making us think about who gets heard.

Echoes on the Plateau: Pema Tseden’s Farewell

Pema Tseden’s Snow Leopard shows how people and nature fit badly together, like his other movies did. The film moves slow and tells many stories at once, pure Tseden style – each shot stays quiet, each fight feels big and sure to happen.

The big empty land of Tibet works like another person in the movie, showing how alone people are, how much they want holy things. This last movie has Tseden mixing small stories with big ideas better than ever, making something as hard to catch as the big cat itself.

Pema Tseden made films that changed things softly. His movies showed real Tibetan life – full of holy things, fighting with new ways, trying to stay friends with nature. His art brought Tibet’s untold stories to movie screens all over. Snow Leopard looks pretty yet scary, never says what’s right or wrong, and makes a good last movie from someone who made art that crossed lines and will keep making people think.

The Review

Snow Leopard

Snow Leopard shows how badly nature and humans mix, with Pema Tseden's eye for pretty pictures. Many small stories come together, the camera makes things look amazing, and big life questions float through it all. The movie mixes good and bad, different ways of thinking, and what it takes to stay alive. Tseden's last film puts the cold, big Tibetan hills next to the small fights of the people who live there. The movie asks deep life questions while saying goodbye to one of Tibet's best movie makers.

PROS

- Stunning cinematography captures the Tibetan plateau's vastness and isolation.

- Thought-provoking exploration of moral ambiguity and existential themes.

- Dreamlike sequences deepen the spiritual and philosophical resonance.

- Strong performances that evoke raw human emotions.

- Pema Tseden’s signature contemplative style, blending realism with mysticism.

CONS

- Slow pacing may deter viewers seeking conventional storytelling.

- Ambiguity in the resolution could frustrate audiences craving closure.