From the moment “Being Maria” opens on a sun-dappled Paris street, you feel the pull of an unwritten destiny. Maria Schneider (Anamaria Vartolomei) isn’t just a young woman chasing stardom—she’s a vessel for something far more volatile: the collision of art and personal integrity.

Director Jessica Palud and co-writer Laurette Polmanss adapt Vanessa Schneider’s memoir with a keen eye for how fleeting moments on camera can haunt an entire lifetime. At 19, Maria’s leap from obscurity into Bernardo Bertolucci’s world-altering “Last Tango in Paris” sets the stage for a narrative that asks: when “truth” on film comes at the cost of a performer’s agency, who truly benefits?

Palud’s rhythm shifts from hushed, intimate sequences—Maria practicing lines, stealing a shy smile from her estranged father—to jolting recreations of on-set betrayal. The film’s tone vacillates between warm nostalgia for a restless teen and cold scrutiny of a filmmaking process unbound by consent. In these early scenes, you sense the calm before a storm: Maria’s luminous eagerness undercuts the undercurrents of exploitation that will soon surface.

Fragments Before and After the Fall

Three years before that infamous butter scene, we meet Maria as a seventeen-year-old craving approval. Reconnecting with her dad, Daniel Gélin (Yvan Attal), delivers both hope and heartbreak—her mother’s fury at old betrayals fuels Maria’s yearning to belong. Palud spaces these family moments deliberately, allowing each glance and half-spoken line to foreshadow Maria’s fragile sense of self.

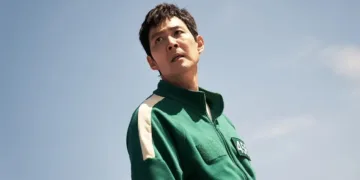

Enter Bernardo Bertolucci (Giuseppe Maggio) in a café: he senses “something wounded” and casts her anyway. Maria’s naïve excitement—her voice cracking at the promise of cinematic immortality—sets up the shock to come.

Then, in a single sequence, Brando’s improv and Bertolucci’s silent agreement strip Maria of preparation. The butter-lubricated moment, shot largely in handheld close-ups, captures Maria’s genuine panic. Her tears land with raw force because they aren’t acted.

The fallout is immediate and multilayered. As press tour lights blaze, Maria is coached to “sell the dream,” her trauma repackaged as publicity. We catch glimpses of tabloid headlines and tearful interviews, each montage splice reinforcing how her identity is slipping through editorial fingers.

In the decade that follows, Maria drifts through ill-fitting roles—each demanding her to bare more than skin—before finding brief refuge in a journalist’s sympathetic gaze. Every episode circles back to that moment of violation, reshaping her from ingénue to survivor.

Portraits in Motion

Anamaria Vartolomei anchors the film with a performance that balances wide-eyed vulnerability and combustible defiance. In pre-Tango scenes, her soft inflections and hesitant smiles convey Maria’s hunger for connection. After the shooting wraps, Vartolomei’s micro-expressions—tightened jaw, shuttered eyes—speak volumes about a spirit recoiling from its own image.

Matt Dillon’s Marlon Brando avoids mimicry, opting instead for an aura of paternal warmth that fractures into complicity when the cameras roll. His measured tone in off-camera exchanges—“It’s only a film”—underscores the gulf between celebrity indulgence and real harm. Giuseppe Maggio’s Bertolucci thrives in tight shots that capture his elegant posture and insistent gaze; his dialogue choices echo a director more in love with his vision than with the young woman embodying it.

Yvan Attal and Marie Gillain bookend Maria’s familial world: Attal’s Gélin offers hollow praise that rings with distance, while Gillain’s mother channels both fear and fierce protection. Palud’s camera stays locked on Maria, filtering every supporting performance through her evolving lens.

Pacing shifts deliberately: long, steady takes build empathy before the pivotal scene, then editing fractures perspectives to mirror Maria’s disorientation. Key lines—Maria’s sharp “That was not good!”—cut through the haze, and moments of silence amplify the weight of her unvoiced pain.

Frames of Resonance

Pierre-David Guetta’s period design transports us to early ’70s Paris: muted earth tones give way to chill blues as Maria’s world fractures. Costumes shift from carefree florals to drab work garb post-Tango, visually echoing her psychological descent. During the butter scene, Palud switches from locked-off masters to jittery hand-held coverage, intensifying the sense of violation.

Benjamin Biolay’s sparse strings flutter beneath dialogue-free moments, allowing ambient on-set chatter—crew prompts, Brando’s murmured directions—to stand out. This interplay of diegetic sound envelops us in the filmmaking machine, making the intrusion feel all the more personal. Editing contrasts a linear build-up with jump-cut vignettes of Maria’s later life—bouts of addiction, fleeting companionship—mirroring her shattered self-perception.

Several themes pulse through every frame: the cost of pursuing “artistic truth” when it erases individual agency; the power imbalance of male directors and stars shaping a young woman’s identity; the struggle to reclaim one’s narrative beyond a single role; and the way trauma fragments memory, looping back into every new choice. As a holistic experience, “Being Maria” interrogates whether the sheen of cinematic legend can ever justify the cracks it leaves behind in human lives.

Being Maria premiered in the non-competitive Cannes Premiere section at the 77th Cannes Film Festival on May 21, 2024, and was released in France on June 19, 2024.

Full Credits

Director: Jessica Palud

Writers: Jessica Palud, Laurette Polmanss

Producer: Marielle Duigou

Cast: Anamaria Vartolomei (Maria Schneider), Matt Dillon (Marlon Brando), Giuseppe Maggio (Bernardo Bertolucci), Céleste Brunnquell (Noor), Yvan Attal (Daniel Gélin), Marie Gillain (Marie-Christine Schneider), Jonathan Couzinié (Michel Schneider), Stanislas Merhar (Behrmann), Alexis Corso (Nathan)

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): Sébastien Buchmann

Editor: Thomas Marchand

Composer: Benjamin Biolay

The Review

Being Maria

“Being Maria” is a haunting, visceral portrait that balances intimate character study with jarring recreations of on-set betrayal. Anamaria Vartolomei’s performance anchors Jessica Palud’s fractured storytelling, creating an experience that lingers long after the credits roll—even when its pacing fragments the narrative.

PROS

- Anamaria Vartolomei’s deeply felt lead performance

- Director’s immersive point-of-view cinematography

- Raw recreation of the pivotal “Last Tango” scene

- Sparse, evocative score that heightens emotional beats

- Thoughtful exploration of power dynamics and agency

CONS

- Fractured pacing in the post-Tango segments

- Surface-level treatment of Maria’s later career

- Occasional reliance on familiar “rise-and-fall” tropes

- Underdeveloped secondary characters

- Abrupt narrative jumps that can feel disorienting