Christian Swegal’s “Sovereign” opens not with fanfare but with the quiet desperation of foreclosure notices piled on a kitchen table—a fitting metaphor for a nation drowning in its own contradictions. Set against the backdrop of Arkansas in 2010 (when the Tea Party was brewing and economic anxiety was curdling into something darker), this feature debut examines the true story of Jerry Kane, a self-proclaimed “sovereign citizen” whose rejection of governmental authority would spiral into tragedy.

The film follows Jerry (Nick Offerman) and his teenage son Joe (Jacob Tremblay) as they exist in a liminal space between society and its margins. Jerry conducts seminars on tax avoidance and property rights to audiences of the economically desperate, while homeschooling Joe in both mathematics and conspiracy theories. Parallel to this narrative runs the story of police chief John Bouchart (Dennis Quaid) and his son Adam (Thomas Mann), creating a diptych of American fatherhood that will converge in inevitable violence.

What emerges is not merely a thriller about fringe extremism, but a meditation on how personal trauma metastasizes into political pathology. The sovereign citizen movement—once relegated to militia compounds and conspiracy newsletters—now seems prophetic of our current moment, when institutional distrust has become mainstream currency.

The Performer’s Paradox

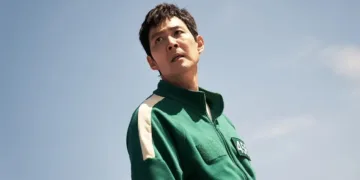

Offerman’s Jerry Kane represents perhaps the most challenging transformation in recent memory: the metamorphosis of comedic persona into genuine menace. The actor, best known for his deadpan libertarian Ron Swanson, here excavates the darker implications of anti-government sentiment. Jerry emerges as a figure of volcanic charisma—part snake oil salesman, part genuine believer, part broken father desperately trying to make sense of senseless loss.

The performance works precisely because Offerman refuses to distance himself from Jerry’s appeal. When Jerry delivers his pseudo-legal rhetoric (“conveyances” instead of cars, “traveling” instead of driving), the actor invests each syllable with pentecostal conviction. This isn’t a man playing dress-up in extremist ideology; this is someone who has found salvation in semantic gymnastics and constitutional cherry-picking.

Tremblay, meanwhile, navigates the precarious transition from child actor to mature performer with remarkable skill. Joe Kane becomes a study in adolescent cognitive dissonance—simultaneously devoted to his father and yearning for the normalcy represented by his neighbor’s window light. The actor captures something essential about inherited extremism: how children absorb their parents’ worldview like secondhand smoke, often without realizing they’re being poisoned.

The supporting ensemble operates with clockwork precision. Quaid’s police chief embodies institutional authority without cartoonish villainy, while Mann’s rookie cop represents the next generation’s struggle with inherited systems of power. Martha Plimpton, in her brief appearances as Jerry’s girlfriend, suggests how desperation can make even the most reasonable people susceptible to unreasonable ideas.

The Grammar of Dread

Swegal’s directorial approach might be termed “empathetic objectivity”—a stance that refuses both condemnation and endorsement of its subjects. The film’s parallel structure (Kane family versus Bouchart family) creates a kind of societal mirror, reflecting two sides of American authority: those who reject it and those who embody it.

The Arkansas setting becomes more than backdrop; it transforms into a character study of post-industrial decay. VFW halls, roadside motels, and suburban homes on the brink of foreclosure create a geography of abandonment that explains, if not excuses, Jerry’s appeal to the dispossessed.

Yet the film’s structural ambitions occasionally exceed its grasp. The police subplot, while thematically relevant, feels underdeveloped—a missed opportunity to explore how institutional power shapes the men who wield it. Swegal seems more comfortable in Jerry’s conspiracy-addled world than in the bureaucratic reality of law enforcement.

The pacing builds with mechanical precision toward its inevitable climax, creating what might be called “documentary dread”—the peculiar tension that comes from knowing historical outcomes while hoping somehow for different endings.

The Pathology of Powerlessness

“Sovereign” operates as a case study in what we might call “trauma nationalism”—the process by which personal grief transforms into political rage. Jerry’s radicalization begins with the death of his infant daughter and his wife’s subsequent pneumonia death, tragedies that government autopsy requirements somehow amplified into systemic betrayal.

The film’s exploration of father-son relationships reveals how extremism perpetuates itself through generational transmission. Jerry doesn’t simply teach Joe to reject authority; he creates a parallel reality where such rejection becomes necessary for survival. Meanwhile, John Bouchart’s tough-love approach to parenting his police officer son suggests how institutional violence gets passed down like family heirlooms.

The economic anxieties of 2010 provide the perfect breeding ground for Jerry’s message. His seminars target people facing foreclosure—individuals for whom the system has already failed. The film suggests that sovereign citizenship fills a spiritual void created by economic abandonment, offering the illusion of control to the demonstrably powerless.

Perhaps most disturbing is how the film illustrates the circular nature of authority and resistance. Jerry’s complete rejection of governmental legitimacy mirrors the police department’s emphasis on compliance through force. Both sides operate from positions of absolute certainty, creating conditions where violence becomes the only possible resolution.

The sovereign citizen movement, as portrayed here, represents something like “libertarian apocalypticism”—the belief that individual freedom requires the complete destruction of collective institutions. Jerry’s worldview contains no space for compromise, negotiation, or incremental change.

The Cinematography of Collapse

Swegal’s visual approach mirrors his thematic concerns, creating what might be termed “realist decay”—a aesthetic that finds beauty in abandonment without romanticizing poverty. The cinematography captures the unglamorous reality of rural Arkansas: strip malls, chain motels, and subdivisions that already look like future ruins.

The film’s dialogue achieves remarkable authenticity, particularly in Jerry’s pseudo-legal jargon. Swegal avoids the temptation to make Jerry’s conspiracy theories obviously ridiculous; instead, he allows the character’s internal logic to reveal its own contradictions. The writing suggests extensive research into sovereign citizen rhetoric, lending Jerry’s speeches a disturbing verisimilitude.

The climactic violence receives matter-of-fact treatment that refuses glorification or exploitation. Swegal understands that real violence lacks the choreographed beauty of Hollywood action sequences—it’s quick, brutal, and final. The film’s refusal to provide cathartic resolution reflects the senseless nature of the actual events.

Perhaps most impressively, the film maintains visual consistency without calling attention to its craft. The cinematography serves the story rather than dominating it, creating an atmosphere of decline that feels both specific to Arkansas and universal to post-industrial America.

The Weight of Witnessing

“Sovereign” succeeds as both historical document and contemporary warning. Offerman’s performance alone justifies the film’s existence, transforming what could have been a simple cautionary tale into something approaching Greek tragedy. The actor reveals how charisma and pathology can coexist, how genuine love can produce devastating consequences.

The film’s refusal to provide easy answers reflects the complexity of its subject matter. Jerry Kane isn’t simply a monster—he’s a casualty of systems that failed him before he failed them. This doesn’t excuse his actions, but it explains their appeal to audiences similarly abandoned by institutional America.

Yet the film’s structural limitations prevent it from achieving true greatness. The police subplot, while thematically relevant, lacks the development necessary to justify its prominence. The parallel structure feels more like conceptual exercise than narrative necessity.

The film’s political stance—or lack thereof—may frustrate viewers seeking clearer condemnation of extremist ideology. Swegal’s empathetic approach risks being mistaken for endorsement, though careful viewing reveals his moral position.

“Sovereign” arrives at a moment when its subject matter feels urgently relevant. The sovereign citizen movement has evolved from fringe curiosity to mainstream political force, making Jerry Kane’s story feel prophetic rather than historical. The film serves as both cautionary tale and diagnostic tool, revealing how personal trauma becomes political weapon.

This is necessary cinema—flawed but essential, uncomfortable but illuminating. Swegal has created a film that refuses to provide comfort while demanding attention. In our current moment of institutional distrust and political extremism, “Sovereign” offers no solutions, only understanding. Sometimes, that’s enough.

Full Credits

Director: Christian Swegal

Writers: Christian Swegal

Producers: Nick Moceri

Executive Producers: Adam Anders, Tom Ortenberg, Adam Ropp, Adam Wyatt Tate, Bennett Litwin, Blake Elder, Colin Bates, Danielle Mandel, Grant Mohrman, Jason Jaggard

Cast: Dennis Quaid, Jacob Tremblay, Terry J. Nelson, Bobby Gilchrist, Kezia DaCosta, Nick Offerman, Megan Mullally, Ruby Wolf, Buddy Campbell, Tom Kramer, Jared Carter, Jennifer Nesbitt-Eck, Mike L. Thomas, Cheryl Vanwinkle, Jason Cochran, Chris Greene, Jade Fernandez, William Sherman, Astrid Allen, Alonso Rappa, Martha Plimpton, Jason Scott Morgan, Thomas Mann, John Trejo, Brandon Stewart, Barry Clifton, Andrew Ortenberg, Nancy Travis, Krishna Sistla Ward, Julia Watts, Chris Pierce, Tommy Dion Burns

Director of Photography: Dustin Lane

Editors: David Henry

Composer: James McAlister

The Review

Sovereign

Anchored by a terrifying, career-defining performance from Nick Offerman, "Sovereign" is an essential and disturbingly relevant study of American extremism. It powerfully diagnoses how personal trauma metastasizes into political pathology. While its structural ambitions are occasionally undermined by an underdeveloped police subplot, the film succeeds as a necessary, challenging, and illuminating piece of cinema that demands to be seen.

PROS

- A transformative and menacing lead performance from Nick Offerman.

- A mature and skilled supporting performance by Jacob Tremblay.

- Timely, relevant, and complex exploration of extremism and institutional distrust.

- An authentic script and a palpable sense of "documentary dread."

- An empathetic but unflinching directorial approach.

CONS

- The parallel police subplot feels underdeveloped and less compelling.

- The film's structural ambitions occasionally exceed its narrative grasp.

- It misses an opportunity to fully explore the institutional side of its central conflict.