Adam Wong’s “The Way We Talk” arrives at a moment when cinema is grappling with authentic representation, yet it transcends the typical disability narrative by focusing on the mechanics of communication itself. The Hong Kong director, known for his nuanced portrayals of youth identity, constructs a story that operates on multiple levels—as a coming-of-age drama, a social critique, and an examination of how we choose to connect with the world around us.

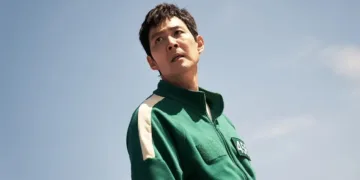

The film centers on three deaf friends whose divergent approaches to communication create both conflict and understanding. Wolf (Neo Yau) champions sign language as cultural expression, Sophie (Chung Suet Ying) struggles with her cochlear implant identity, and Alan (Marco Ng) navigates between both worlds with practiced ease.

Set against Hong Kong’s historical oralism policy—which banned sign language in schools until 2010—the narrative explores how institutional decisions shape individual identity. Wong doesn’t construct this as a simple advocacy piece but as a complex examination of choice, autonomy, and the different ways we adapt to societal expectations.

The Architecture of Identity

Wong’s character construction demonstrates sophisticated understanding of how personal history shapes present choices. Sophie’s arc from cochlear implant ambassador to sign language advocate follows a classical transformation structure, but Wong avoids the typical epiphany moment. Instead, her evolution unfolds through accumulated experiences—workplace discrimination, communication barriers, and the gradual realization that her mother’s choices may not align with her own needs.

Wolf emerges as the film’s most politically charged character, yet Neo Yau’s performance prevents him from becoming a mere symbol. His passion for diving serves as both character detail and metaphor—the underwater world offers him a space where communication transcends sound. When systemic barriers prevent him from pursuing his dreams due to lack of sign language interpretation, the story reveals how individual aspirations collide with institutional failures.

Alan, portrayed by deaf actor Marco Ng, represents the film’s most complex position. His fluency in both spoken and sign language makes him a bridge between communities, but this positioning also isolates him. Ng’s performance captures the subtle exhaustion of constant translation—not just linguistic, but cultural and emotional. The chemistry between the three leads feels authentic, avoiding the forced intimacy that often plagues ensemble dramas.

The casting choices create interesting narrative tension. While Ng’s authentic experience adds credibility to Alan’s character, Neo Yau and Chung Suet Ying’s learned sign language performances raise questions about representation that the film doesn’t directly address.

Sound and Vision as Narrative Tools

Wong’s technical approach serves the story’s thematic concerns through carefully crafted sensory experiences. The sound design functions as a primary storytelling mechanism, shifting perspectives to immerse viewers in different auditory worlds. When we experience Sophie’s cochlear implant reality—voices bleeding into static, conversations becoming fragmented noise—the film demonstrates rather than explains her daily challenges.

The contrast between Wolf’s muffled, nearly silent world and Alan’s clearer audio landscape creates empathy without manipulation. Wong’s visual style remains deliberately understated, allowing these audio shifts to carry emotional weight. The cinematography focuses on faces and hands, emphasizing the physicality of communication while avoiding the typical “disability film” visual language.

Flashback sequences revealing the oralism policy’s impact on Wolf and Alan’s childhood education integrate seamlessly with the present narrative. These scenes don’t function as simple exposition but as character revelation, showing how institutional decisions created lasting personal divisions. The recurring ocean imagery—particularly Wolf’s diving sequences—provides visual metaphor without overshadowing the human story.

Wong’s directorial restraint prevents the film from becoming overly sentimental while maintaining emotional accessibility. The pacing allows character development to breathe, avoiding the rushed revelation structure that often undermines disability narratives.

Beyond Binary Choices

The film’s greatest strength lies in its refusal to position cochlear implants and sign language as opposing forces. Instead, Wong examines how external pressures—family expectations, workplace demands, educational policies—restrict individual agency. Sophie’s transformation doesn’t reject her cochlear implant but embraces additional communication methods, suggesting that identity can expand rather than shift.

The workplace discrimination sequences reveal how “diversity” initiatives often mask deeper institutional failures. Sophie’s experience as a corporate “mascot” exposes the gap between performative inclusion and genuine accommodation. Wolf’s rejection from diving instruction due to interpretation barriers demonstrates how systemic inflexibility perpetuates exclusion.

Family dynamics receive careful attention, particularly Sophie’s relationship with her mother. Their conflict represents generational trauma—the mother’s desire for her daughter’s “normalcy” stems from protective instincts shaped by historical discrimination. The film suggests that understanding, rather than judgment, can bridge these generational gaps.

Wong’s approach to the oralism controversy avoids simple condemnation while acknowledging real harm. The educational flashbacks show how well-intentioned policies can create lasting damage, but the film focuses on recovery rather than blame. This nuanced stance reflects contemporary disability discourse’s shift toward autonomy and choice.

The film positions itself as social commentary without sacrificing emotional resonance. Wong understands that effective advocacy emerges from authentic character experiences rather than political messaging. “The Way We Talk” succeeds as both intimate character study and broader cultural critique, demonstrating how personal stories can illuminate systemic issues without losing their humanity.

Full Credits

Director: Adam Wong

Writers: Adam Wong, SeeKing, Ho Hong

Producers: Adam Wong, Jacqueline Liu, Ho Hong

Cast: Neo Yau, Chung Suet Ying, Marco Ng

Director of Photography: Leung Ming Kai

Editors: Adam Wong, Jason Yiu, 1000springs, Poon Po-yan

Composer: Day Tai

The Review

The Way We Talk

"The Way We Talk" represents sophisticated filmmaking that balances social advocacy with authentic character development. Wong's nuanced approach to disability representation, combined with innovative sound design and genuine performances, creates a film that educates without preaching. While casting choices raise representation questions, the emotional depth and technical craft make this essential viewing for understanding contemporary disability discourse.

PROS

- Innovative sound design that immerses viewers in different auditory experiences

- Nuanced character development avoiding stereotypical disability narratives

- Authentic exploration of communication choices and institutional barriers

- Strong performances, particularly Marco Ng's genuine portrayal

- Thoughtful examination of family dynamics and generational trauma

CONS

- Two hearing actors portraying deaf characters raises authenticity concerns

- Some didactic moments that feel overly instructional

- Pacing occasionally slows during exposition-heavy sequences

- Limited exploration of broader deaf community beyond the three protagonists