The cicadas are screaming. It’s the first thing you notice in The Summer Hikaru Died, a relentless, high-pitched thrum that blankets the sleepy rural village of Kubitachi in a thick layer of summer heat. It’s the kind of idyllic, pastoral setting where teenagers are supposed to be bored, not terrified.

Here we find Yoshiki and Hikaru, lifelong friends whose bond is the town’s only real point of interest. That is, until Hikaru wanders up a mountain, vanishes for a week, and comes back… different.

Most horror tales would spend episodes teasing out the mystery, letting the dread build in stolen glances and unsettling moments. This series has no time for that. Within the opening minutes, Yoshiki, armed with the unshakable certainty of a true best friend, looks at the smiling boy beside him and cuts straight to the point: “You’re not Hikaru, are you?”

The question hangs in the humid air, not as an accusation, but as a statement of fact. The show immediately discards the “what happened?” for a far more disturbing question: “What do you do when the monster wears the face of the person you love most?”

A Deal with the Devil You Know

The entity’s confession isn’t a villainous monologue; it’s a bizarrely pathetic plea. Having taken over Hikaru’s dying body on the mountain, this creature—this thing—simply wants to enjoy the perks of being human. It likes the food, the sun, the world.

And, inheriting Hikaru’s memories, it likes Yoshiki. Its request is simple: keep the secret, let’s stay friends, and please don’t make me kill you. It’s a threat delivered with the casual innocence of a child, a chillingly effective cocktail of affection and menace. This isn’t an invasion; it’s a transaction.

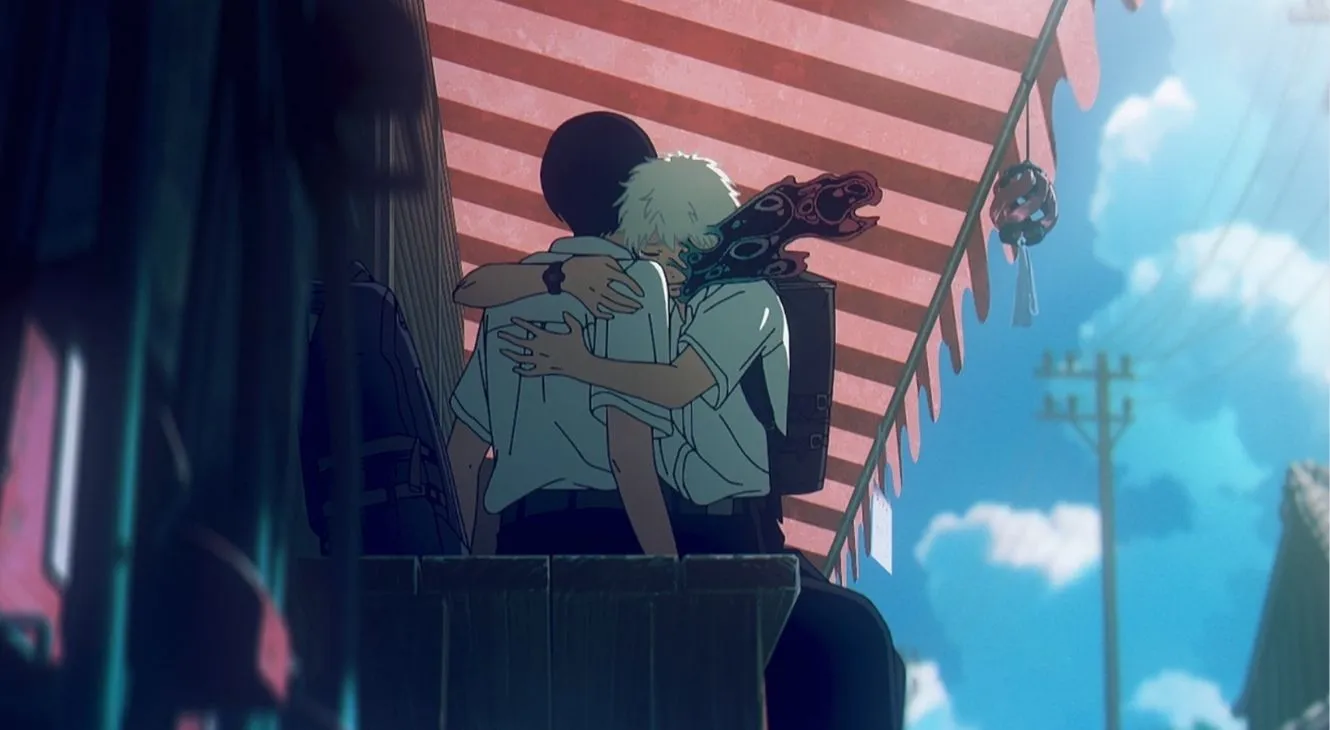

For Yoshiki, the choice should be simple. It isn’t. Drowning in a grief so absolute it has hollowed him out, he’s not just mourning a friend; he’s mourning the quiet, unstated romance that defined his world. The show paints his loneliness in stark, painful strokes—a boy so broken by loss that any semblance of his former life feels like a lifeline.

So he makes his terrible bargain. He agrees to the lie, choosing the warmth of a monster in his best friend’s skin over the cold reality of being alone. It’s not a heroic sacrifice. It’s a profoundly selfish act of survival, a decision born from a desperation so deep it’s willing to embrace the grotesque.

And so, Yoshiki gets to keep his Hikaru, or a version of him, anyway. But the cost is immediate. He becomes a co-conspirator in his own haunting, his days now a tightrope walk of anxiety and feigned normalcy. The series posits that the true horror isn’t the creature from the woods, but the one we willingly invite into our lives to avoid facing the truth. Yoshiki chose the ghost, but the real haunting is just beginning.

It Wears a Snaggletooth and a Smile

The creature wearing Hikaru is a master of mimicry. It has the memories, the mannerisms, and the goofy snaggletoothed grin down perfectly. It remembers every shared joke and carries the same tender affection for Yoshiki that the original did.

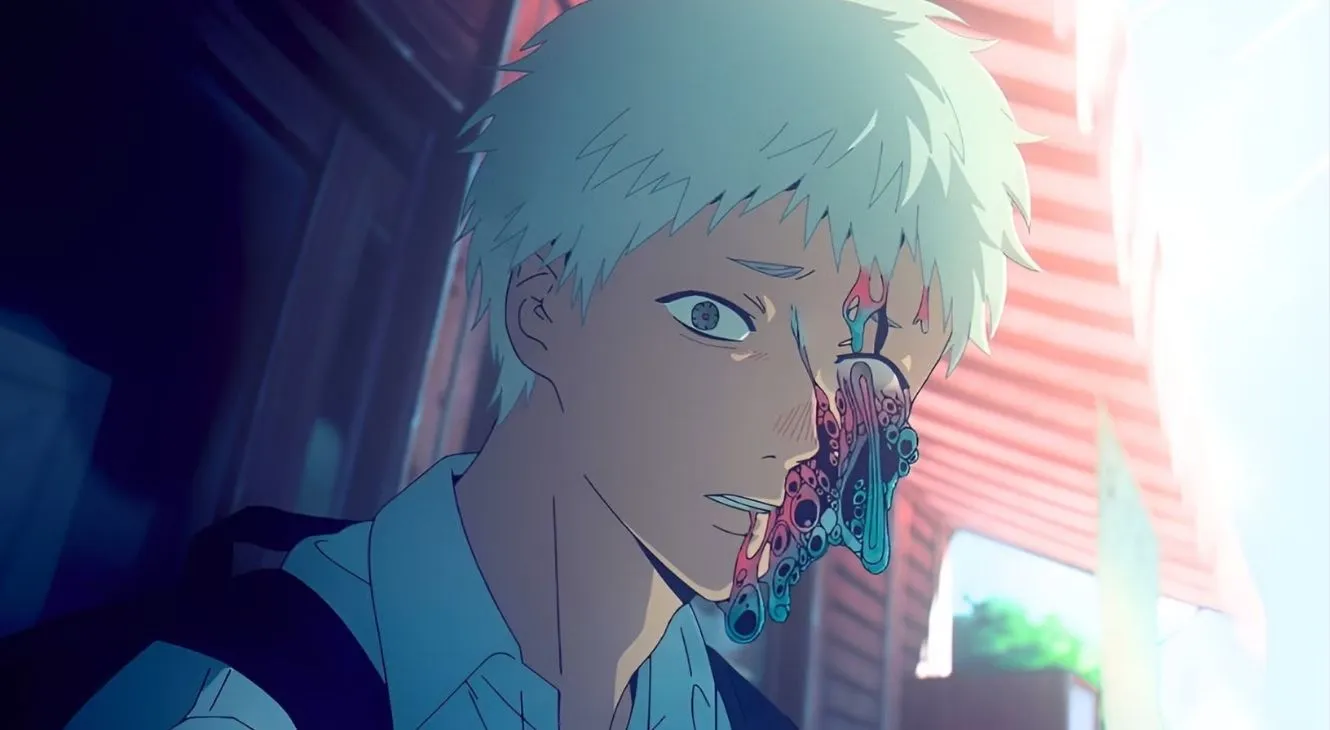

But this is no simple doppelgänger. The performance is flawless, right up until it glitches. In moments of stress or intense emotion, the mask slips, and we get a flash of the eldritch horror beneath—an eye dissolving into a kaleidoscopic nightmare, a perspective so alien it defies human logic. This isn’t just a monster in a skin-suit; it’s a being playing a role with a script it only partially understands.

What makes “Hikaru” so deeply unsettling is its unnerving combination of childlike wonder and latent menace. It approaches human life with the wide-eyed curiosity of a newborn, discovering the simple joys of ice cream and music for the first time.

This innocence is disarming, making the moments of wrongness even more potent. A cat recoils in terror, an old woman screams at the sight of it, and we’re reminded that this is an ancient thing, a power from the mountain that doesn’t operate by our rules. The horror comes from its unpredictability; it’s a creature that could offer you a flower or tear you apart with the same detached curiosity.

Much of the credit for this balancing act goes to voice actor Shūichirō Umeda, who delivers a masterclass in duality. His Hikaru is bright, warm, and utterly convincing, but he can inject a subtle flatness, a flicker of something hollow and inhuman, that sends a chill down your spine. The performance perfectly captures the central terror of the show. You’re never sure if the affection it shows Yoshiki is a genuine, emerging emotion, or just the echo of a dead boy’s feelings, played back with perfect fidelity.

The Village Has Eyes

Kubitachi isn’t just any sleepy, rural town; it’s the kind of place with secrets buried under every rice paddy. This isn’t the first time something has come down from the mountain. The villagers whisper of “Nonuki-sama” and failed rituals, their fear laced with a grim familiarity.

This isn’t a story about a town’s first contact with the supernatural; it’s about the latest chapter in a long, losing battle. The setting itself becomes a character—a place steeped in a history of folklore so dark it feels less like myth and more like a collection of old police reports. The oppressive summer heat suddenly feels less like weather and more like the lid on a boiling pot.

Yoshiki’s secret was never going to stay private. The entity’s presence begins to bleed into the community, starting with the gruesome death of an old woman who saw the monster for what it was. Her murder elevates the threat from a personal tragedy to a public menace. Enter Tanaka, a cynical, sunglasses-at-all-times agent for some shadowy organization that hunts things like “Hikaru.”

He’s the outside world crashing the party, the professional who confirms that this small-town horror is part of a much larger problem. His arrival is a classic genre trope, but it effectively shatters Yoshiki’s contained nightmare, forcing it onto a much bigger, more dangerous stage.

The narrative now operates on two distinct, terrifying tracks. There is the intimate, psychological horror of Yoshiki’s grief-stricken bargain, and then there is the unfolding supernatural thriller threatening to consume the entire village. The story is no longer just about whether Yoshiki can live with his lie, but whether anyone in Kubitachi will live at all.

A Beautiful, Terrible Thing

Visually, The Summer Hikaru Died is a study in contrasts, a gorgeous pastoral painting defaced with graffiti from another dimension. The direction often lulls you into a false sense of security with sun-drenched landscapes and slice-of-life vignettes that feel almost Ghibli-esque in their beauty. Then, without warning, the frame fractures.

The entity’s true nature erupts in flashes of grotesque body horror and abstract, psychedelic animation that feel ripped from a different, far more disturbing show. This visual dissonance is the series’ greatest strength, weaponizing its own beauty to make the horror hit harder. It’s a style that honors the source manga’s aesthetic while using the full power of the animated medium to create an atmosphere of profound unease.

The sound design operates on the same principle. Those ever-present cicadas aren’t just background noise; they are the story’s heartbeat, a constant thrum of summer life. The most terrifying moments are not marked by a loud sting, but by the sudden, deafening silence when the cicadas stop. It’s a brilliant use of negative space that signals something is deeply wrong.

This patient pacing, which allows for quiet, emotional moments to breathe between the dread, makes the horror feel earned rather than cheap. The show understands that true terror isn’t a constant scream, but a slow, creeping dread that builds in the silence.

Ultimately, what anchors this high-concept horror is the raw, painfully human performance of Chiaki Kobayashi as Yoshiki. He voices the character with a palpable sense of exhaustion and frayed nerves, his breaths catching in his throat, his words choked with a grief he can’t express.

It’s a performance that grounds every supernatural event in emotional reality, reminding us that for all the monstrous happenings, this is a story about a boy who has lost his world. The show’s greatest horror may be how beautifully it captures the ugly, desperate bargains we make with ourselves just to survive another day.

The Summer Hikaru Died premiered on July 5–6, 2025 on Nippon TV and launched globally on Netflix the same weekend.

Full Credits

Director: Ryōhei Takeshita

Writer / Series Composition: Ryōhei Takeshita

Producers and Executive Producers: Cygames Pictures, Nippon TV, Netflix

Cast (voice): Chiaki Kobayashi, Shūichirō Umeda, Yumiri Hanamori, Rie Kurebayashi, Chikahiro Kobayashi, Yoshiki Nakajima, Yuki Tadokoro

Composer: Tarō Umebayashi

The Review

The Summer Hikaru Died

The Summer Hikaru Died is a masterful exercise in atmospheric horror, brilliantly juxtaposing idyllic summer beauty with grotesque terror. It trades cheap jump scares for a profound, creeping dread rooted in the raw, human agony of grief. Anchored by outstanding voice performances and a bold narrative that confronts its central mystery head-on, the series is a haunting, visually arresting exploration of love and loss. It masterfully illustrates how the monsters we accept are often more terrifying than the ones we fight. This is a beautiful, unsettling, and essential watch.

PROS

- Stunning visual direction that contrasts beauty with body horror.

- Exceptional voice acting that grounds the story in palpable emotion.

- A deeply unsettling atmosphere built on expert sound design and pacing.

- A mature and poignant exploration of grief, love, and identity.

- Bold narrative structure that gets straight to its terrifying premise.

CONS

- The deliberate, slow-burn pacing may not appeal to all viewers.

- Graphic body horror elements can be intense for some.

- Focus is more on psychological dread than action-based thrills.