In the fast-paced world of modern body horror, “Else” stands out as a stunning first book that breaks the rules of the genre. In this fascinating film, directed by Thibault Emin, a small apartment is turned into a place where love, terror, and change all come together in a way that is hard to believe.

This French movie Fever Dream goes beyond typical horror tropes to deeply reflect on how people bond and define themselves. At its core, “Else” looks at what happens when close ties aren’t just emotional but could also be physical. The movie is about Anx and Cass, two different people thrown together during a strange virus outbreak that turns people and things into grotesque, collective beings.

Emin’s idea goes beyond the usual way of telling viral stories. In this case, the virus is both a metaphor for and a real cause of change that makes people think about the lines between themselves and their surroundings. The apartment becomes a small version of change, where personal space changes as quickly as relationships do.

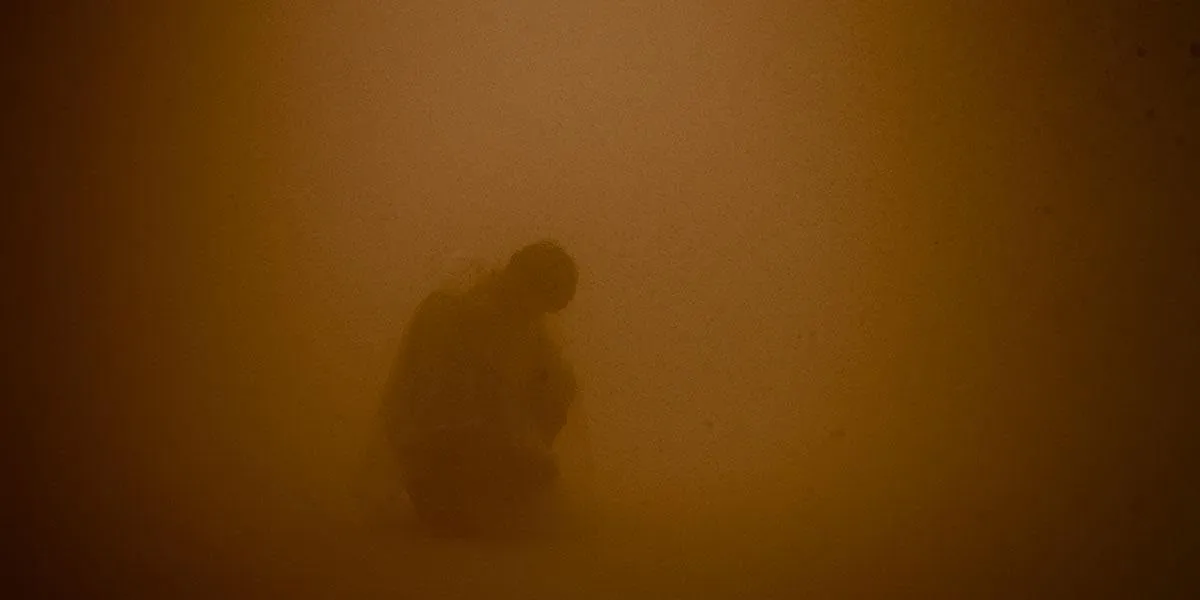

“Else” moves between romantic comedy, body horror, and surreal science fiction. It’s a film with bold visuals and deep psychological ideas. The colour scheme changes a lot, from bright colours to stark black-and-white, which shows how the characters’ sense of who they are is falling apart. Cinematographer Léo Lefèvre makes beautiful and scary pictures, making the horrible seem strangely romantic.

“Else” examines human frailty, connection, and the constant change of life by reimagining viral transmission as a form of radical intimacy.

Merging Realities: A Virus of Intimacy

Think of a party where links form between people who don’t know each other before, like stray electricity. In this way, Anx and Cass crash into each other—two opposites drawn together by a strange magnetic force. He is a shy, nervous introvert whose room looks like a child’s. She is a brave, spontaneous party girl. Their energy is instant, messy, and impossible to predict.

But when an unknown virus spreads through the city, love takes a sharp and scary turn. This is not a normal story about a pandemic. This virus does more than just attack; it changes things. People start to blend in with their surroundings; phones become skin-like extensions, sidewalks eat up human flesh, and everyday items start to pulse with an alien consciousness.

As the couple is trapped in Anx’s small room, their playful mood changes. Through air vents, sounds from nearby neighbours drift in, like whispers of changes happening far away. The outside world falls apart as they try to keep their tenuous bond together, going back and forth between tender moments and basic survival reflexes.

The room takes on a life of its own, with walls that breathe and move. What starts out as a safe place slowly turns out to be a healthy, hungry place. As surfaces move and ripple, the lines between building and inhabitants become less clear. Every item becomes a possible threat, and every touch becomes a possible joining.

Their relationship becomes a small version of bigger philosophical questions: Where do I end and you begin? What happens when people’s identities fall apart? The virus doesn’t just attack bodies; it questions the idea of being different.

As the epidemic gets worse, Anx and Cass alternate between fighting the change and giving in to its strange, unavoidable reasoning. It’s less about fighting to stay alive and more about handling this new, frightening closeness.

The apartment goes from being a love haven to a nightmare cocoon, with every surface having the potential to come to life and every moment full of the possibility of change. They’re not just lovers anymore; they see how people have completely changed.

Symbiosis of Strangers: Personalities Colliding

Anxiety is like having a panic attack on your body. His apartment, which is arranged like a child’s play area, says more about him than any words could. He is shy around other people and very careful. He’s like a tightly wound spring—always ready for a possible link and the inevitable disappointment that comes with it.

Cass comes along, a storm of unchecked energy and careless spontaneity. She improvises where Anx figures things out. While he avoids talking to people, she happily breaks social rules by the handful. She’s the type of person who would have casual sex during a viral end of the world, which happens to be the case.

Their relationship turns into an honest, surprising test of how well two people can get along. Imagine putting two chemical elements that don’t mix close. They would be volatile, dangerous, and weirdly magnetic. Cass doesn’t mind that Anx is cautiously shy; it seems to interest her. Her crazy energy doesn’t overwhelm him; it gives him a surprise support system for his weak social interactions.

Their relationship is changing at the same rate as the mysterious virus breaking down bodily barriers. Their main differences start to show in the way they talk to each other. Anx’s carefulness balances out Cass’s carelessness. Her bravery breaks down his carefully built mental walls.

Survival is less about protecting yourself as an individual and more about adapting as a group. They’re no longer just friends or roommates; they’re two organisms learning to work together as a hybrid whole. They use their different personalities to help each other stay alive by making up for each other’s flaws.

Anx and Cass learn that relationships aren’t about how similar two things are in this nightmare world of viral metamorphosis. They’re about combining things that don’t seem to go together to make something new.

Metamorphic Visions: Horror’s Liquid Landscape

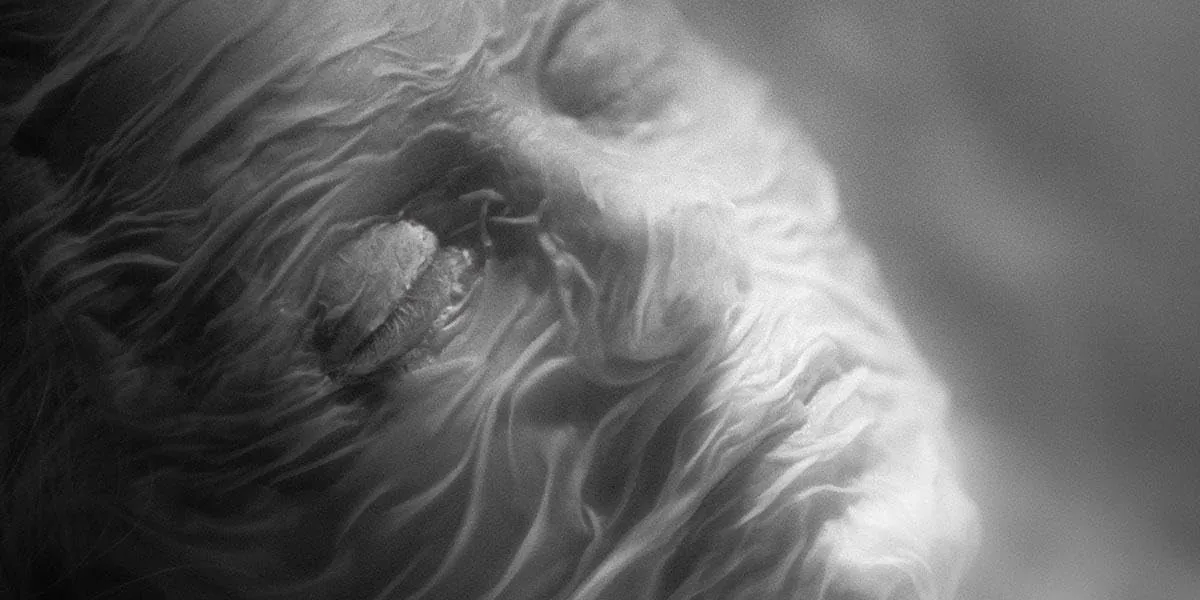

Cinematography by Léo Lefèvre is more than just pictures telling stories; it’s a live, breathing thing. Imagine a camera that moves like a nervous system, taking close, shaking shots of people showing their vulnerability. Each frame pulses with a disturbing organic energy that changes the everyday into something completely strange.

The colour scheme takes on a life of its own. The bright colours that started fade into black and white and then change into a sickly, disturbing yellow as if a fever dream were coming true. This trip through colour shows how the characters’ minds are falling apart, and the colour becomes a symbol of change.

Special effects go beyond the usual scary methods. Walls do more than just move; they breathe, ripple, and eat away at things. In ways that are both gross and fascinating, objects merge with human flesh. Imagine a sidewalk taking on the shape of a person or a phone becoming an extension of skin. These aren’t just tricks; they say deep things about people’s flexibility.

“Else” looks great because it’s a great mix of low-tech science fiction and body horror. Think of early David Cronenberg mixed with experimental film, where the horrible turns out to be surprisingly beautiful. The movie looks like a crazy dream sent through film, and every frame pushes viewers out of their comfort zones.

The flat goes from a simple place to a living, beating thing thanks to Lefèvre’s camera work. Walls turn into skin, and surfaces turn into membranes. Each frame makes it seem like nothing is fixed. The visual language is a dialect of mutation, where the lines between people, things, and the world always rebroken rebuild rebuilt

Dissolving Boundaries: When Humanity Liquefies

“Else” isn’t just a scary movie; it’s also a psychological playground where you can mix up your ideas about who you are. Think of identity as a thin skin always at risk of breaking completely. The virus is no longer just a biological threat; it’s also a question of what it means to be human at our core.

Transhumanism is at the story’s heart. It raises interesting questions, like “What happens when we’re no longer separate beings?” The movie turns the scary idea of losing oneself into a real, physical experience. Every moment of fusion is a deep psychological negotiation: where do I stop and the other person begin?

Anxiety about the virus is still going strong below the surface. The tight flat becomes a miniature version of the world’s loneliness, with a thin line between closeness and fear. Anx and Cass’s friendship is a lot like how we all felt during the pandemic: pushed together, under a lot of mental stress, and with a strange closeness that comes from having to survive together.

The virus is a metaphor for more than just changing how you look. It brings to life existential dread—a harsh warning that our limits are less solid than we’d like to think. Each merger is a small loss of individual identity, replaced by something scary and possibly transcendent.

Under the horror, philosophical questions arise: Is being connected a nightmare or the next step in our evolution? Do we lose who we are when we merge with others—with lovers, places, or shared experiences? Or do we find something deeper?

The answer “else” isn’t always easy to find. Instead, it shows change as an ongoing, messy process of becoming, where horror and beauty interact in a shocking and stunning way.

Viral Convergence: Dissolving Into Everything

“Else” doesn’t have a typical horror crescendo at the end; instead, it has a psychological implosion. The apartment goes from being a safe place to stay to being a live thing that eats its residents. Walls’ bodies start to look and feel like Anx and Cass’s as they pulse and breathe. The system is being eaten away at their humanity one layer at a time.

In the most disturbing parts of the movie, there is no longer any difference between people and the world. Imagine that skin turned into wallpaper, bones turned into structural beams, and awareness seeped into the apartment’s foundation. The fear is unbearable—a beautiful nightmare of being completely connected.

The ending doesn’t give a simple answer. Instead, it presents an enthralling scene of change. Anx and Cass are no longer two separate things. They’ve changed into something completely different—part people, nature, and collective awareness. It’s both a death and a rebirth simultaneously, a scary and strangely peaceful surrender.

What comes out is neither fully human nor fully alien. The last few pictures show a very close relationship in which each person’s personality is lost. They have been eaten, but they have also been raised, combined, and washed over.

The virus doesn’t just wreck; it builds new things. At its deepest, “Else” asks: Is total breakdown a loss, or is it the closest link something could ever have?

Metamorphic Visions: Rewriting Human Boundaries

Thibault Emin doesn’t just make scary movies; he also sets off a psychological quake. “Else” turns out to be more than just a horror movie; it’s a new take on what horror can do. Emin challenges every common story about connection, identity, and survival by turning personal human experiences into a visceral study of change.

This isn’t scary stuff that makes you jump and scream. This is a horror that slowly but surely seeps into how you see yourself. Emin uses closeness as a weapon, making personal weakness a place where people can change who they are. Each frame poses a thought-provoking question: What if our limits are less solid than we think? What happens when the link between people turns into a real-life fusion?

The beauty of the movie is that it doesn’t give easy answers. Instead, it takes viewers on a confusing and stunning journey where beauty and horror are hard to tell apart. People will probably talk about “Else” in hushed, reverent tones for a long time after the movie ends, breaking down its many levels of meaning.

This is more than a story about an outbreak or a body horror experiment; it’s a deep reflection on how people can change. Emin says that the things that scare us the most might also be the things that change us the most; losing oneself could be another way of becoming completely new.

The Review

Else

"Else" is an interesting attempt at filmmaking that breaks typical horror movies' rules. Thibault Emin has made a deeply disturbing and philosophical look at how people connect, who they are, and how they change. The movie breaks down barriers between genres by combining body horror with a close look at a single character. It offers a powerful reflection on what it means to truly connect in a world increasingly broken up. People who just want simple scares should not watch this movie. Instead, it's a mental and emotional maze that will test, bother, and eventually change anyone willing to give in to its unique vision. Emin's risky way of telling stories makes for a frightening experience that stays with you long after the last frame. The genius of the movie lies in how it uses body horror as a metaphor for how vulnerable people are, how isolating they can be during an outbreak, and how thin the lines are between people's identities. It's both beautiful and gross, close and scary simultaneously.

PROS

- Innovative and groundbreaking visual storytelling

- Profound philosophical exploration of identity and connection

- Exceptional cinematography by Léo Lefèvre

- Unique body horror approach that transcends genre conventions

- Powerful performances by lead actors

- Thought-provoking metaphorical narrative

CONS

- Potentially challenging narrative for mainstream audiences

- Abstract storytelling might confuse some viewers

- Graphic body horror elements could be disturbing

- Complex philosophical themes may feel inaccessible