The desire for a clean, controlled exit from life is packaged as a luxury consumer product in House of Abraham. The film’s premise is distinctly a product of a certain Western cultural moment, where wellness branding can be applied to even the most final of acts.

We are introduced to a secluded, elegant home in the woods, a structure of sharp lines and wide glass panes that feels more like a high-tech retreat in Silicon Valley than a place to die. The atmosphere is one of profound and eerie calm. Into this meticulously managed environment arrives Dee, a woman carrying both a terminal diagnosis and the visible weight of a deep trauma.

Her presence immediately signals a disruption. She is not just another guest seeking a quiet end; she is a catalyst, a variable that the house’s perfect system was not designed to handle. The film establishes its central tension by placing her skepticism against the house’s serene, yet absolute, certainty.

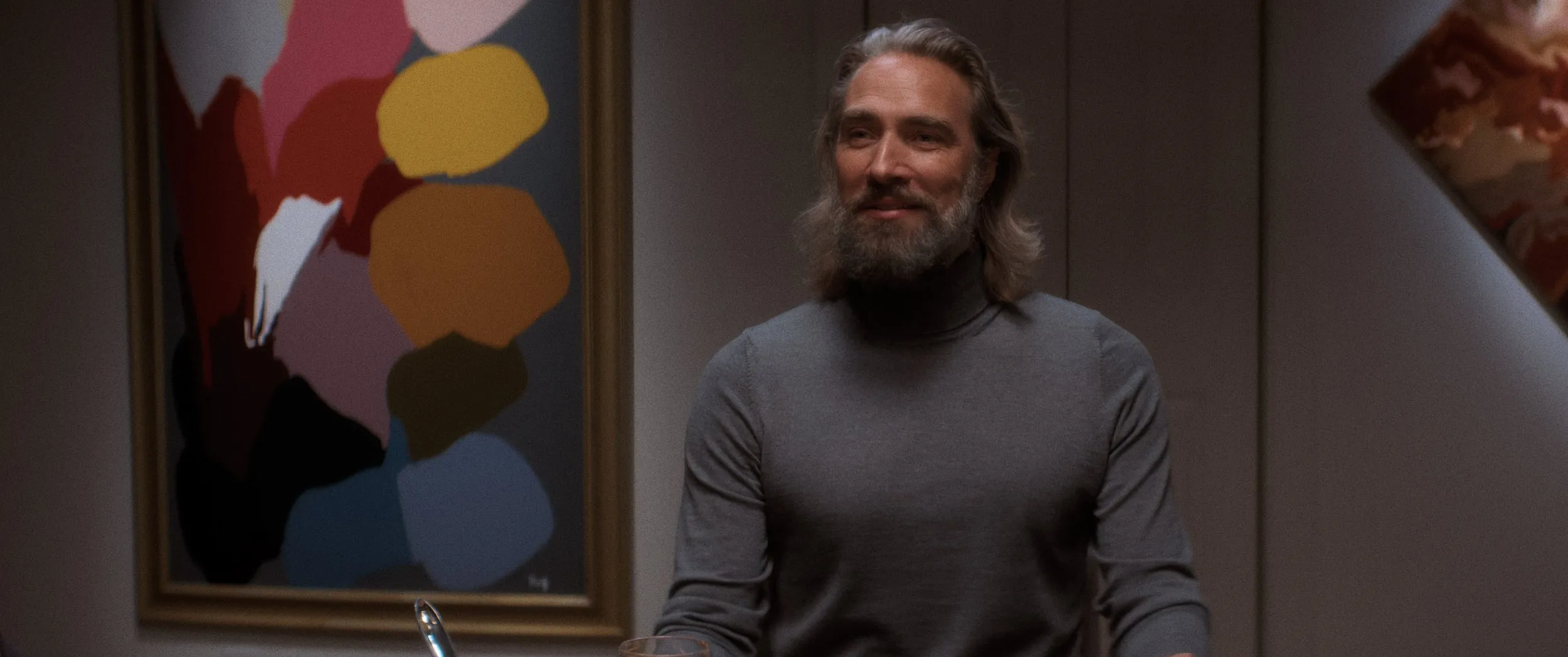

The Prophet of the Curated Self

At the center of this world is Abraham, the retreat’s proprietor. He is less a traditional prophet and more a creation of the modern age of self-help gurus and charismatic tech CEOs, a figure who blends the aesthetic of a bohemian artist with the cold logic of a startup founder.

His physical presence—long hair, a groomed beard, an athletic build—evokes a very specific type of Western counter-culture figure, now repurposed to sell a high-end service. His core philosophy, “Life is not for everyone,” is a chilling perversion of existentialist thought, stripping it of its emphasis on responsibility and twisting it into a slogan that justifies surrender.

He is aided by his assistant Beatrice, whose true-believer status is perhaps more frightening than Abraham’s rhetoric. Her cheerful adherence to the grim protocol, her warm smiles while leading people to their doom, represents the terrifying banality of a system where functionaries execute their duties without questioning the morality of the machine.

The house rules—the surrender of phones, the formal dinners, the specific rituals—create a closed ecosystem, an echo of high-control groups that isolate individuals to make them more susceptible to a new, all-encompassing reality.

A Congregation of the Dispossessed

The film populates its sterile house with varied forms of human pain, each a quiet indictment of a specific societal failure. Dee stands apart from the other guests as an active, intellectual resistor. Her skepticism is not just a gut feeling; it is a form of immunity granted by her past trauma.

Having truly stared into the abyss, she cannot be fooled by someone who has only theorized about it. Her presence forces a collision between a clean, forward-looking ideology and the messy, inescapable reality of human history. The other guests are a gallery of contemporary despair. A couple consumed by guilt reflects a justice system that offers punishment but not restoration.

An elderly man with a grim prognosis points to a cultural fear of aging and a loss of dignity within an impersonal medical system. Their stories ground the film’s high concept, making the house a microcosm of a society that offers few authentic solutions for suffering, leaving its members vulnerable to radical, commodified alternatives. They form a temporary, fragile community, a dark mirror of the support groups that are a fixture of Western therapeutic culture, yet this one is predicated on mutual destruction rather than mutual healing.

Glitches in the Utopia

The narrative’s tension escalates through Dee’s refusal to conform, depicted through visual storytelling that emphasizes her alienation. The film uses the house’s architecture—its cold surfaces and transparent glass walls—to create a sense of constant surveillance. Dee’s movements are tracked by a camera that feels both voyeuristic and judgmental, casting her as a rogue element in a flawless design.

This cat-and-mouse game becomes a physical navigation of a hostile system, like a player-character mapping out a level in a game to find its weaknesses. The film’s horror is rooted in its depiction of death as a synthetic, corporate ritual. The grey robes, the champagne toast, the final recorded statement—these rites are devoid of any genuine cultural or spiritual tradition.

They stand in stark contrast to the rich, complex funeral traditions of many other cultures which aim to connect the individual to community and history. The House of Abraham’s ritual does the opposite; it severs all ties, completing the process of alienation. The true horror is not gore, but the system’s placid, efficient acceptance of its grim function, a terror born from radical individualism taken to its logical conclusion.

Ideology as Architecture

The story reaches its peak in a final confrontation that is less a physical struggle and more an ideological showdown. It is a battle of narratives: Abraham’s abstract, universalizing, and cleanly articulated philosophy against Dee’s specific, personal, and messy lived experience.

The film’s resolution, where Dee’s raw trauma dismantles Abraham’s theories, is its core statement. It proposes that history and pain hold a greater truth than any detached, intellectual ideal. This is a feature debut for director Lisa Belcher, who uses the film’s visual design to reinforce its themes.

The sleek, minimalist production design is the aesthetic of corporate wellness, a visual language that promises control while masking exploitation. The sharp cinematography by Alex Walker presents this world with a clinical polish, making the house itself a metaphor for the hollow core of the salvation it offers.

While the film ultimately lands on a message of perseverance—a perhaps quintessentially American response to profound despair—it does not shy away from the seductive allure of giving up, leaving a lingering, and effective, sense of unease.

“House of Abraham” is a horror/thriller movie that was released in select theaters on June 13, 2025. It was distributed by Abramorama.

Full Credits

Director: Lisa Belcher

Writers: Lukas Hassel

Producers: Lisa Belcher, Paul Merryman, Melissa Kirkendall

Executive Producers: Sidney Ganis, Vance Hinton, Priscilla Hinton, Natasha Henstridge, Lin Shaye, Lukas Hassel, Wally Welch

Cast: Natasha Henstridge, Lin Shaye, Lukas Hassel, Gary Clarke, Marval A. Rex, Lisa Belcher, Kelsey Pribilski, Khali Sykes, Sean Freeland, Aria Goodson, William Magnuson, Vance Hinton, Doug Kennedy, Jeffro Hardwick, Kenneth Belcher

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): Alex Walker

Editors: Lars Gustafson

Composer: Steffen Schmidt

The Review

House of Abraham

House of Abraham is a sharp and unsettling psychological thriller that succeeds as a potent cultural critique. Using its chilling premise to dissect the intersection of wellness culture and radical individualism, the film is anchored by strong performances and a tense, clinical atmosphere. While its narrative may not surprise all viewers and its ultimate message on perseverance feels somewhat conventional, it remains a smart, thought-provoking piece of independent filmmaking. It intelligently explores the hollow core of modern, commodified solutions to profound human suffering, making it a disturbing and worthwhile watch.

PROS

- An intelligent and original premise that serves as a strong hook.

- A sharp cultural critique of wellness culture and extreme individualism.

- Strong performances from the lead actors, particularly Lukas Hassel and Natasha Henstridge.

- A tense, clinical atmosphere sustained by effective direction and cinematography.

CONS

- The plot's primary twists may be predictable for some viewers.

- A lack of subtlety in its dialogue and thematic presentation at times.

- Key supporting actors, like Lin Shaye, feel underutilized.

- The final resolution can feel like a conventional answer to the complex questions raised.