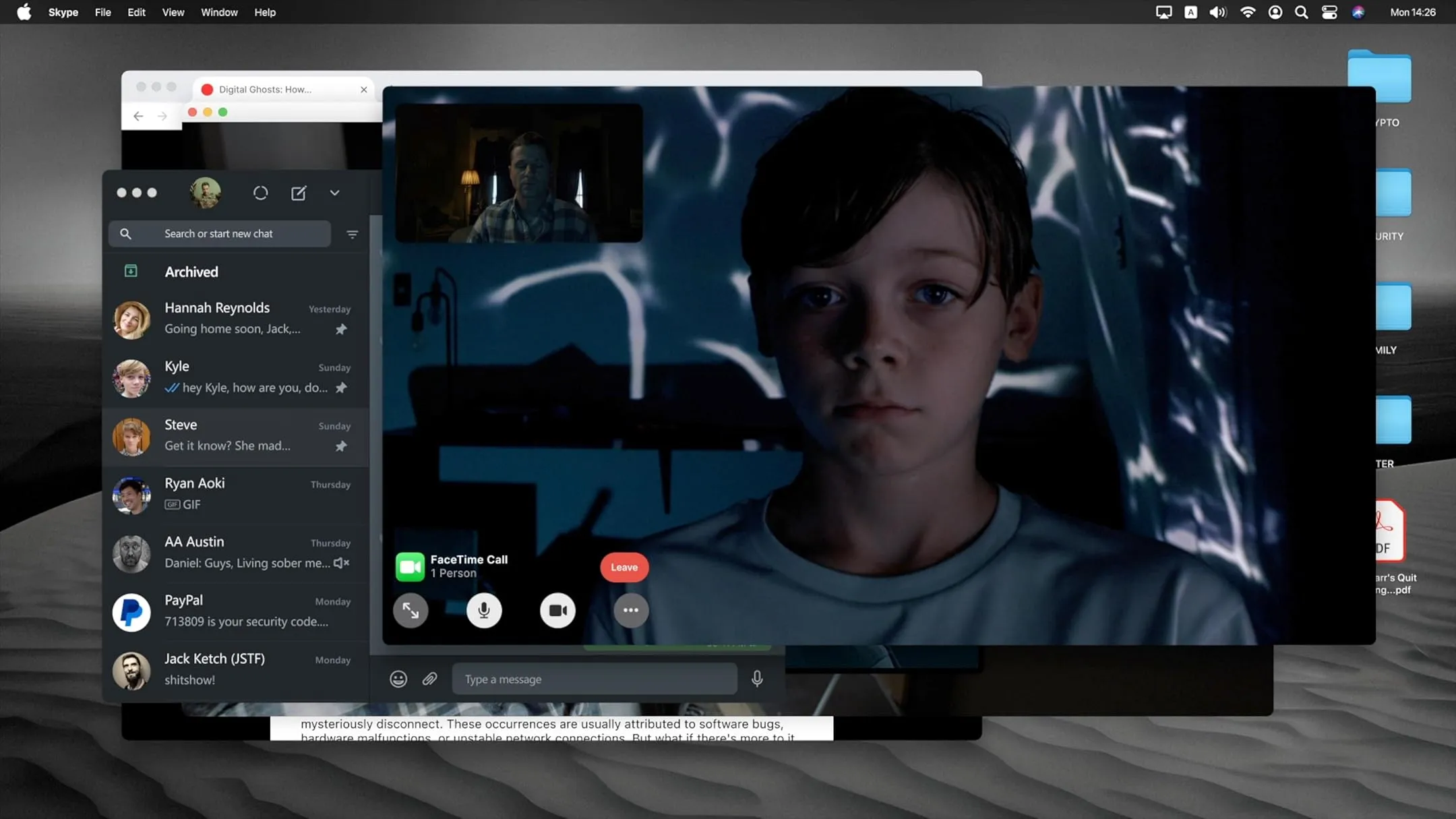

Jack Reynolds sits before a Mac desktop that feels more cockpit than family archive (his grief exposed via open browser tabs, half‑sent text threads). When his wife and sons set off for what Hannah calls the Japanese countryside after a stillbirth, Kyle’s near‑drowning becomes a screen‑bound mystery. A flash of green sludge in a FaceTime call shatters faith in digital distance.

Bloat stages its terror inside windows, apps and notification pings. FaceTime replaces tracking shots. A sudden glitch can summon something ancient. Jack toggles between drone strikes abroad and cloud drives at home, excavating folklore from dark‑web corners. The film marries folk‑horror’s murky waters with pixel‑ated specters—what Absento might dub “browser‑borne dread.” And yes, no one said typing could be so frightening.

At times the format itself falters—a non‑diegetic score crashes in, a hidden camera creeps beyond the screen’s borders (a cinematic faux pas, by design or accident). Yet those slips underscore the tension between real‑time empathy and artificial connection.

Is this a family drama or a technological parable? When paternal duty collides with bandwidth limits, questions emerge: what does it mean to guard loved ones through glowing rectangles? How does a foreign myth warp under Western surveillance? Bloat’s opening gambit invites us to consider fear’s new frontier—one measured not in footsteps down a haunted hallway, but in cursor clicks and buffering icons.

Rituals of Grief in Pixel and Pond

Jack and Hannah carry a private sorrow. Ava’s stillbirth casts a shadow over every keystroke and Facetime ping (that hospital video is never far from Jack’s desktop). Their two sons—Steve, on the cusp of adolescence, and ten‑year‑old Kyle, buoyant one minute, withdrawn the next—inhabit a family portrait shattered by loss.

Then comes a sudden call from Tokyo. Jack’s bereavement leave is revoked after militia strikes on U.S. bases pull him back into his NATO AI operations. Hannah refuses to cancel the vacation; she’ll press on, carrying grief and two boys across oceans. Her choice feels heroic—but also haunted, as if she’s chasing a mirage of normalcy.

The inciting blow arrives in a lake’s murky depths. Kyle nearly drowns, then coughs up viscous green sludge during a video chat. A single frame. A frozen image. A demon’s calling card. Behavioral glitches follow: sudden cravings for cucumbers, furtive nocturnal wanderings. Kyle becomes an enigma displayed in low resolution.

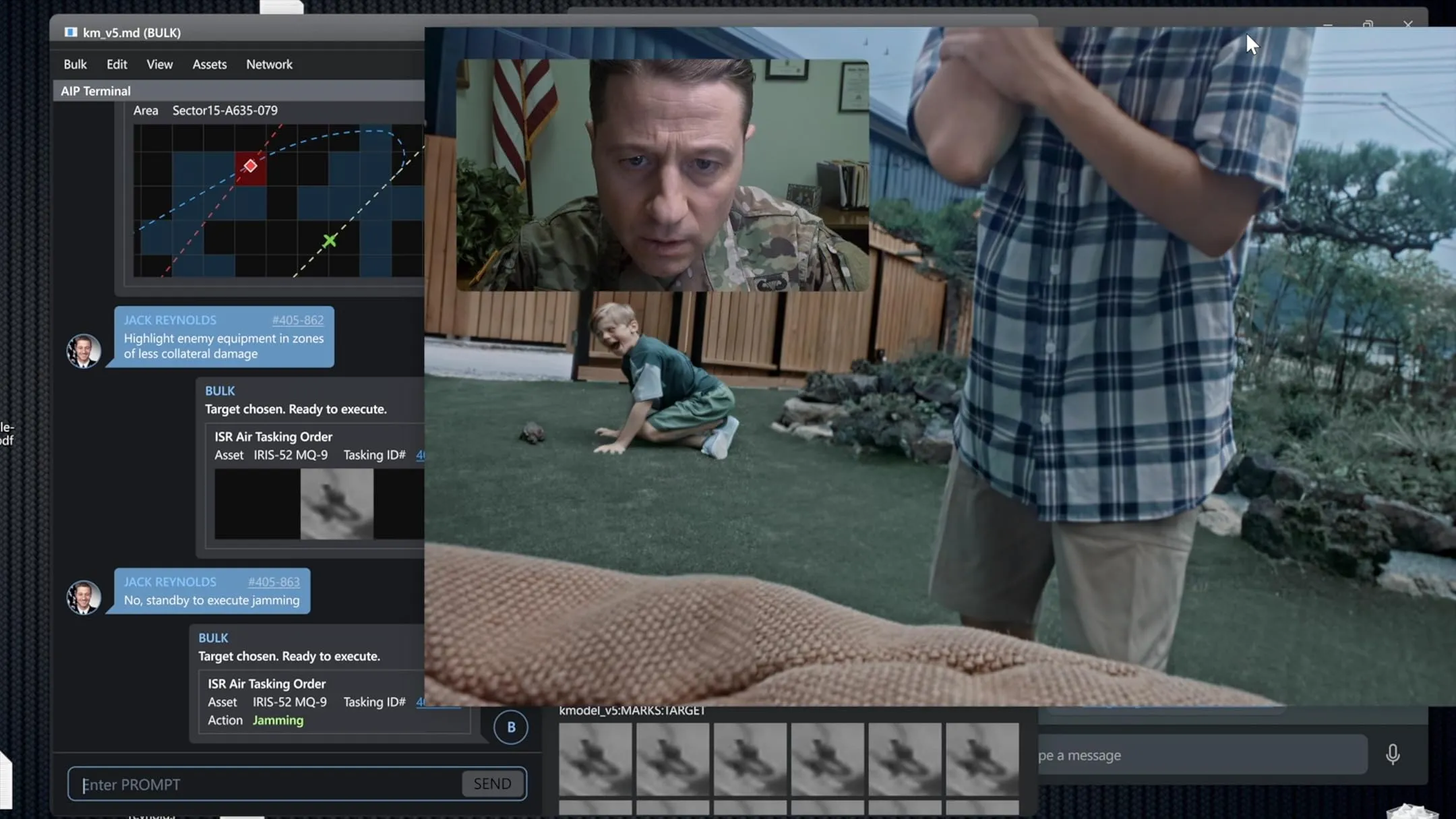

Jack turns detective. He scours shared cloud folders, scrolls through Instagram geo‑tags, infiltrates a “Parents of Possessed Kids” forum (a phrase Absento might label “screen‑age exorcism”). He outfits the rental home with webcams. He pilots drones over Japanese woodlands. Each new feed tightens the noose of remote helplessness.

In his search, Jack uncovers the tragic legend of Derrick Gray, an American father whose own boy succumbed to a similar fate—and landed Gray behind bars. Folklore points to a Kappa, an amphibious specter hungry for children. The myth feels collateral damage in a world where every phone camera can double as a portal.

As Kyle’s condition spirals, digital screens flicker with spectral interference. Jack’s greatest weapon—technology—edges toward impotence. The climax looms: a married clash between Western surveillance culture and ancient Japanese ritual. A final reveal imperils our faith in pixel‑based guardianship, teasing a twist that flickers on the verge of the uncanny without ever fully materializing.

Streaming Shadows: The Screenlife Mechanics

The film’s world unfolds inside Jack’s desktop interface—a digital stage where folders like “Photos” and “Crypto” sit beside open browser tabs and FaceTime windows (a domestic cathedral of pixels). In‑screen audio cues—notification pings, keyboard taps—blend with a non‑diegetic score that wafts through scenes like a ghost in the machine. It’s a soundscape that both anchors and unsettles.

Glitches carry weight here. Pixelation isn’t just an aesthetic; it becomes folklore’s cipher. A momentary freeze‑frame can hint at something lurking beyond resolution’s edge. At other times, distortion muddies the reveal, forcing us to question what’s real and what’s buffered illusion.

Editing alternates between slow scrolls through cloud folders and snap‑cut jolts into new tabs. These tempo shifts mirror Jack’s mounting anxiety. Yet dream‑sequence cutaways occasionally break the spell—reflections off the screen slip into third‑person angles, reminding us this is a constructed artifact. A minor sin, perhaps, but one that yanks us from pure screen‑mode immersion.

There are moments when the format shines: a live‑chat window becomes a séance conduit, where text bubbles pulse like ancestral whispers. Then come the artificial breaks, like off‑screen cameras sneaking in, which feel like cinematic cheats (or maybe winks at genre tradition).

Bloat stands on the shoulders of its “Unfriended” and Host predecessors, but it carves its own tributary. Where those films mined social anxieties—cyberbullying, digital voyeurism—this piece interrogates the military’s reliance on remote operations. Tech that kills abroad now struggles to save at home. The result? A hybrid form that reimagines found‑footage codes through the lens of contemporary warfare and domestic surveillance.

Faces Behind the Frame

Ben McKenzie carries Jack Reynolds’s transformation with a quiet insistence. He begins as a methodical AI operator—each keystroke precise, each click purposeful—then shifts into a frantic, wide‑eyed guardian (his voice trembles during those late‑night video calls). That transition rings true: panic doesn’t arrive all at once, but seeps in like a slow leak.

Hannah (Bojana Novakovic) enters with composure intact. In early scenes she issues measured updates—photo synopses of Tokyo nightlife, playful nudges at Steve’s teen sarcasm. Soon, the weight of grief and isolation cracks her facade. Novakovic’s performance flirts with sympathy and frustration; at times she’s our steadfast guide, at others a shadow of doubt (her relapses into wine‑laced texts feel jarring—and oddly human).

Steve (Malcolm Fuller) becomes Jack’s eyes on the ground. He prowls the house with a baby‑cam, doubting every creak and whisper. Fuller balances teenage exasperation with surprising empathy. Kyle (Sawyer Jones), by contrast, embodies metamorphosis: one moment a boy clutching cucumbers, the next, a vessel for something unearthly—his vacant stare fleetingly illuminated by pixelated green.

Kane Kosugi’s Ryan injects dry levity—a “tech shaman” fumbling with VPNs and translation apps. Archive clips of Derrick Gray and brief counsel from a Japanese monk enrich the lore (a “digital folklore,” you might say). These ancillary roles broaden the film’s universe without overwhelming its core.

Family chemistry unfolds in split‑screen choreography. Asynchronous calls underscore the emotional gap between homeland and vacation home. When McKenzie’s Jack and Novakovic’s Hannah exchange overlapping updates, their timing occasionally mismatches, reminding us that true intimacy can’t be manufactured through Wi‑Fi alone. Yet when their pauses align—silence shared across continents—the illusion holds, and the digital veil almost feels transparent.

Pixel Poltergeists and Digital Dérive

“Bloat” fashions its mise‑en‑scène from Jack’s desktop—every folder icon and notification ping feels loaded (an “UI‑driven mise‑en‑scène,” if you will). The menu bar becomes a Greek chorus, commenting on his grief through blinking alerts. In place of elaborate sets, we get Airbnb webcams framing a lakeside cabin in stilted, handheld angles—an exercise in minimalism that doubles as commentary on our era of remote surveillance.

Split‑screens and picture‑in‑picture windows carve the film’s visual grammar. A cool, sterile palette at Jack’s NATO post (steel blues, clinical whites) contrasts with the warmer hues of Japan’s countryside (amber sunsets leaking through webcam glare). The shift echoes the film’s core tension: institutional detachment versus domestic vulnerability.

Sound operates on two planes. Diegetic cues—keyboard clicks, FaceTime chimes, distant drone rotors—anchor us in Jack’s dual role as operator and parent. Then a swelling score intrudes, at times heightening dread, at other moments rupturing immersion (one wonders if Absento intended that dissonance as a wink at genre convention).

Effects are sparing but pointed. The Kappa’s presence remains a spectral suggestion—a murmur of movement in pixelated shadow. Green sludge oozing from Kyle’s mouth registers not as grotesque spectacle but as folklore‑influenced glyph. These glitches, when timed with a cursor hiccup or lag spike, become horror triggers in their own right.

Low‑budget constraints surface as creative catalysts. Lack of widescreen vistas channels focus onto digital details: an open “Crypto” folder, a paused video with eerie background noise. In these micro‑moments, tension accrues more potently than any jump‑scare could deliver. The result is a film where the simplest interface becomes a canvas for existential dread—and perhaps a mirror to our own pixel‑driven anxieties.

Myth and Machine: Symbolic Currents

Jack’s vigil over his family becomes a lesson in remote guardianship. He trades battlefield commands for FaceTime pleas—an inversion of paternal heroism veering into digital impotence. (Which demands more fortitude: ordering a drone strike or ordering emergency services via webcam?) The film holds that tension taut: proximity measured in latency, protection defined by bandwidth.

Grief seeps through every frame. Ava’s stillbirth ripples across Jack’s browser history and Hannah’s wine‑stained texts. Technology offers a balm—shared photo albums, cloud drives—but also a barrier, as curated images replace real embrace. Mourning becomes a playlist of notifications.

Screenlife here doubles as social commentary: modern parenting under surveillance. Each webcam placement echoes historical panopticons, where seeing is power and privacy dissolves. Agency drips away with every unblinking camera.

Folklore rides these currents. The Kappa myth arrives as both novelty and potential appropriation. A Japanese water demon retooled for Western fears (“scripted exorcism,” one might quip). The film flirts with cultural exploration but often leaves context unplumbed, a missed opportunity for cross‑cultural dialogue.

This hybrid form—folk‑horror meets screenlife thriller and family drama—signals a possible evolution. When ancient myth collides with pixelated dread, the result feels precarious yet promising. Bloat suggests that horror’s future may lie in browsing histories as much as haunted woods.

Final Thoughts & Impressions

Bloat earns praise for McKenzie’s seamless transformation—from calm AI operator to desperate guardian—and for its inventive use of desktop interfaces as storytelling tools. Yet abrupt POV shifts and an intrusive score sometimes fracture immersion, and the pacing can lag.

This hybrid thriller will appeal to screenlife enthusiasts, folk‑horror devotees, and anyone drawn to tales of parental anxiety played out through technology. Fans seeking conventional jump scares may feel left adrift.

Absento’s ambition—to weave ancient Kappa myth into a digital surveillance narrative—yields moments of genuine tension. At its best, the format heightens drama; at its most awkward, it undercuts folklore with pixelated artifice.

For maximum impact, watch on a personal device in a low‑light setting (headphones advised). Let every notification chime and glitch flicker draw you into Jack’s remote vigil—and remind you that even virtual threads can stretch to breaking.

Full Credits

Director: Pablo Absento

Writer: Pablo Absento

Producers: Ben McKenzie, Timur Bekmambetov, Anna Shalashina, Pablo Absento, Mariya Zatulovskaya, Marie Garrett, Gilles Sousa, Aleksandr Fomin, Hiroko Oda, Dzhanik Fayziev, Mitch Davis

Cast: Ben McKenzie (Jack), Bojana Novakovic (Hannah), Sawyer Jones (Kyle), Malcolm Fuller (Steve), Kane Kosugi (Ryan), Ethan Herschenfeld (Judge Richard Resnick), Asha Etchison (Reporter), David Gibson (Jack’s Father), Rebecca Nelson (Jack’s Mother), James Adam Lim (Police Officer #2), Miyu Yokota (Sakura), David Lavine (Forensic Expert), Larry Bull (Defense Attorney), Jeff Applegate (Col. William Bradley), Akiyo Komatsu (Officer Ikeda), Zack Niizato (Doctor)

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): Denis Saprykin

Editors: Aleksandr Kletsov, Ilya Zevakin

Composer: Fedor Pereverzev

The Review

Bloat

Bloat captivates through Ben McKenzie’s urgent performance and clever interface design, transforming desktop clutter into a catalyst for dread. Its folklore premise and remote‑guardian concept spark fresh intrigue, though intrusive score cues and sudden POV shifts occasionally strain the illusion. While pacing can be uneven, the film’s marriage of ancient myth and modern surveillance delivers memorable chills. Fans of screenlife horror will find value, though traditional scare‑seekers may be left wanting.

PROS

- Ben McKenzie’s performance conveys raw, palpable urgency

- Desktop interface used as an inventive narrative device

- Folklore integration enriches the thematic fabric

- Minimalist glitch effects generate genuine suspense

- Diegetic sound cues heighten every heartbeat

CONS

- Non‑diegetic score occasionally feels intrusive

- Sudden POV shifts can pull viewers out of the moment

- Mid‑film pacing lags before the final act

- Japanese cultural context remains underexplored

- Climactic twist lacks full emotional payoff