From the first frame, Mom drapes itself in hush and haze, transforming domestic calm into a silent scream. Meredith returns to her suburban refuge clutching newborn Alex, yet the walls seem to close in as if brimming with unseen breath. What begins as an all‑too‑familiar portrait of early motherhood—midnight feedings, fraying patience, and gentle reassurances—quickly fractures into something far more disquieting.

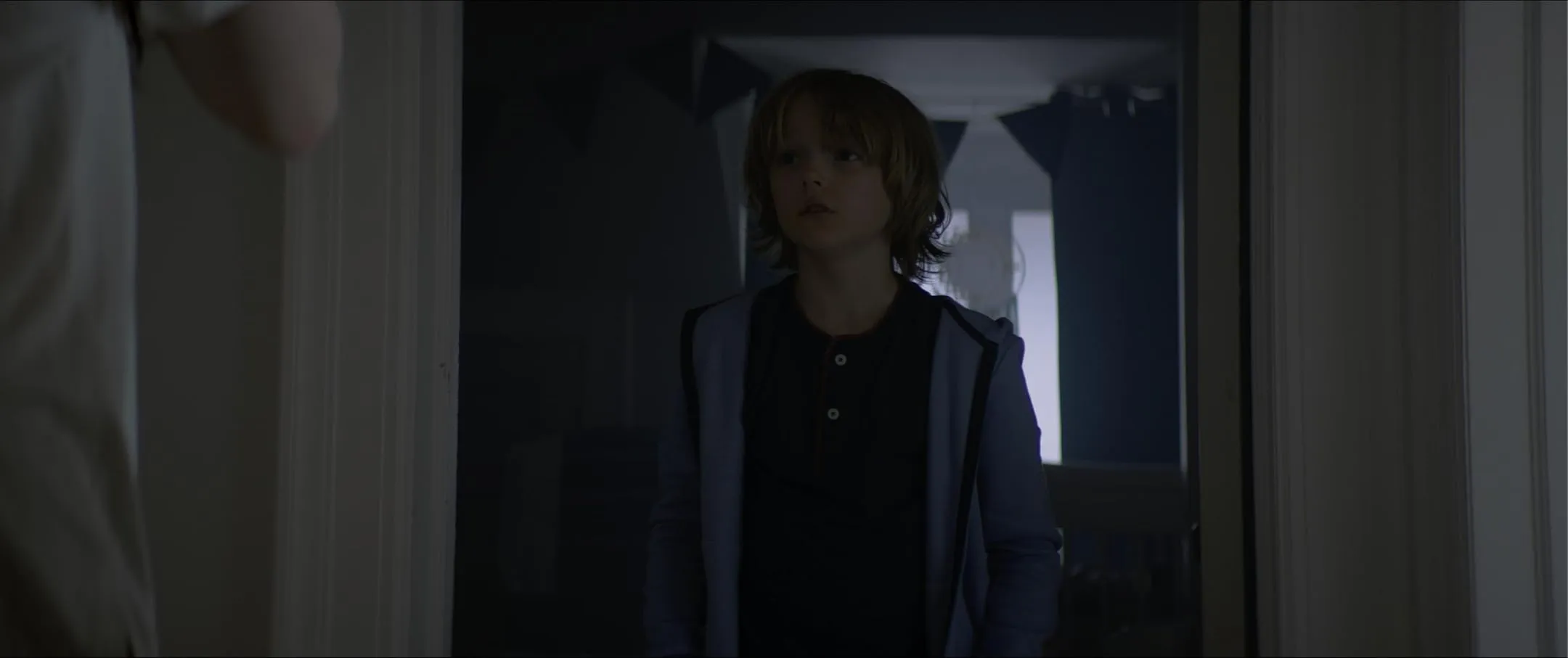

Meredith’s home, once a sanctuary, takes on the guise of a trap: corridors lengthen in pale light, shadows pool beneath cracked baseboards, and every mundane creak hints at a presence lurking just out of sight. Is that stretch of darkness a phantom offering warning, or the projection of her unraveling mind? As postnatal anguish seeps into every crevice, the film challenges the easy distinction between inner and outer threat.

O’Brien frames each scene with a painter’s eye for decay—drips of milk stain pristine floors, blood‑tinted visions swim against drifting laundry, and hallway angles tilt like a mind tipping toward breakdown. We watch Meredith sift through therapy appointments and half‑formed promises from her husband, each moment underscoring her isolation even amid warm lighting and familiar furnishings.

In this opening tableau, Mom demands that we confront the fragile boundary between maternal duty and personal dissolution, setting the stage for a story that tests the resilience of both house and heart.

Blueprints of Disintegration

Act I opens on a facade of domestic bliss: Meredith and Jared glide through their front door, newborn Alex cradled between them. Sunlight spills across spotless floors, only to be stained moments later by a crimson vision of a blood‑soaked crib. The quiet hum of a smoke detector shattered by Meredith’s panicked hand announces that this household’s equilibrium is already fracturing under the weight of sleepless nights, endless feeds, and unspoken expectations.

In Act II, therapy sessions become a gallery of disconnection—Meredith perched on the therapist’s couch while Jared offers well‑intentioned platitudes that drift past her like distant echoes. Walls creak with unnamable murmurs; water leaks through ceiling seams, pooling at her feet as if the house itself is weeping.

Shadows coalesce into figures: an older Alex with knowing eyes, a woman whose face bleeds into long hair, and centipedes that twitch across warped floorboards. Each apparition tightens the spiral, culminating in the bathtub incident that erupts with brutal finality, tearing the narrative’s safety net from under the viewer’s feet.

By Act III, Meredith stands alone in a home transformed into an asylum of her own making. Hallways buckle Repulsion‑style, and every corner harbors her guilt—real or imagined. When she finally confronts the “entity,” the encounter offers no absolution, only a final frame that lingers like a question without an answer.

Fractured Mirrors of Motherhood

The film plunges headlong into the raw circuitry of postpartum depression, laying bare hormonal tremors that ripple through Meredith’s psyche. Intrusive thoughts erupt with the force of nightmares—crimson visions of her baby swaddled in blood, cribs transformed into vessels of dread.

The depiction of psychosis is neither sensational nor reductive; instead, it balances empathy with a stark recognition of how shame festers when a new mother can’t locate her own reflection. Yet the film flirts with exploitation, pressing its horror beats against a very real illness, asking whether we’re witnessing supernatural malevolence or the corrosive impact of internalized guilt.

Momhood here is a battleground of identity. Meredith’s memories of herself—of a woman who once moved freely through the world—clash violently with her current reality. The ritual of expressing milk becomes as fraught as a performance test, every drop weighed against her duty to maintain a “normal” home: roast dinners, tidy floors, social niceties. Each domestic chore not completed becomes another indictment of her failure, and that tension crackles through every scene.

Guilt and grief coalesce into grotesque imagery. The bathtub sequence is especially searing—a tableau that externalizes maternal self‑loathing in tragic detail, as water and blood become indistinguishable. Here, the child she fears she’s harmed manifests as both victim and accuser, embodying Meredith’s remorse and unresolved trauma.

Throughout, the film toys with the line between real horror and mental projection. A flicker of light might signal a ghost or a flicker of memory; dialogue from therapy sessions bleeds into hallucinations, disorienting any attempt to anchor the narrative in objective truth. Flashbacks fracture the timeline, suggesting that every spectral encounter might be a shard of memory or the house’s own sinister will.

That house itself emerges as a character: its peeling wallpaper and buckling floors mirror Meredith’s fracturing mind. Outside, the manicured suburb promises order; inside, the walls weep and whisper. In those cramped, collapsing rooms, loneliness takes shape, proving that confinement—both mental and architectural—can be the most terrifying monster of all.

Shadowplay in Suburbia

Adam O’Brien’s first feature moves with the patience of a stalking predator, trading relentless jolts for a slow‑burn tension that tightens like a noose. Long takes cradle scenes of domestic routine until the camera’s grip feels decidedly unkind—tight framing squeezes Meredith into the margins, as though her world itself conspires to marginalize her.

The color palette reads as a study in decay: walls washed in pallid grays and sickly whites, interrupted by splashes of raw crimson—birth discharge, smeared blood—each hue demanding attention and refusal. Overhead lights cast oblique shadows that pool in corners, hinting at presences just beyond sight, while every bulb flicker becomes an unspoken threat.

Visual motifs anchor the film’s nervous energy: hairline cracks spiderweb across hallway walls, water beads and drips like slow tears, and the lank-haired figure drifts through doorframes with an almost ritualistic inevitability. Cribs heave under unnatural weight, appliances groan and shudder as if alive, and each object feels laden with symbolic dread.

Editing blurs the line between waking and dreaming. Reality splinters through quick cuts, then lingers in extended flashbacks that return the viewer to pivotal moments, only to upend them. This disorientation serves the narrative’s logic: when the mundane and the monstrous fuse, certainty collapses under its own weight.

Haunted Embodiments

Emily Hampshire anchors every distorted frame with a visceral intensity. Her Meredith is a tapestry of exhaustion and edge-of-panic resolve—eyes rimmed with fatigue, voice taut as unspooled wire. In early scenes, Hampshire’s posture whispers the hesitance of a new mother finding her footing; later, each tremor of her limbs and hollowed cheek betrays a mind besieged by fear. She transforms routine infant care into an act of relentless vigilance, her maternal terror both ferocious and achingly human.

François Arnaud walks a tightrope between empathy and indignation as Jared. He inhabits the role of the well-meaning husband whose ignorance cuts deeper than malice. In moments of mockery over Meredith’s research, Arnaud’s casual smirk curdles into guilt; during the scene that sees Meredith committed, his controlled panic underscores how easily concern unravels into helplessness.

Christian Convery drifts through the house as Older Alex, a silent cipher whose cherubic features twist into ominous portent. His stillness fuels unease: a child’s phantom weight, a reminder that loss and longing can wear a living face.

Minor roles—Mariah Inger’s therapist dispensing rote counsel, distant family voices echoing down empty hallways—amplify Meredith’s seclusion. Together, these performances tether the film’s spectral dread to lived-in sorrow, allowing horror to seep from the cracks between human fragility and fractured trust.

Echoes of Dread

The score threads creeping strings through quiet moments, only to snap with sudden stingers that send shivers down the spine. Silence is wielded like a blade—each baby’s whimper, each drip of water, carved into the soundscape to magnify every heartbeat. In the mix, whispers and distant echoes curl around the edges of perception, as if Meredith’s anxieties have taken audible form; low‑frequency rumbles underscore her darkest hallucinations, vibrating through the frame.

Visually, production design furrows the house into a character of decay: peeling wallpaper, water stains blooming across ceilings, and cracks that spider‑web through every corridor. Practical effects—smears of blood on cribs, slick rivulets in the bathtub—feel tactile, resisting CGI’s polish to root the horror in tangible dread.

This technical alchemy—where audio, image, and performance coalesce—sustains an atmosphere that feels alive, pressing in from all sides, and refusing relief.

Between Walls and Whispers

Mom crafts horror not from a leviathan or gnarled beast, but from the slow suffocation of the psyche. Dread roots itself in every lingering shot, privileging mood over monster. The long‑haired specter and dripping water calls back to classic Asian horror, yet here they feel reframed as contours of a fractured mind rather than simple jump scares. This is horror woven from the fabric of domestic routine, where the creak of floorboards and the swell of orchestral strings become the true antagonists.

Visceral shocks—none more wrenching than the bathtub scene—jolt the senses, yet the film’s power lies in the soft tremor that follows. A sudden vision yields to a pregnant silence: a cradle rocking in empty air, Meredith’s ragged breath caught in the lens. Such moments will resonate with aficionados of slow‑burn terror, demanding patience and a willingness to dwell in discomfort. Conversely, viewers craving relentless action or clear‑cut scares may find the film’s deliberate pacing more unsettling than satisfying.

Emotionally, Mom courts both catharsis and unease. It probes the shame and grief tethered to postpartum depression, holding those themes as tender—and potentially triggering—threads. Rather than offering relief, the film leaves trauma unexpurgated, a raw nerve exposed in the sanctum of home. That choice refracts traditional “scare” into an experience that lingers long after the credits roll.

The final frame refuses to confirm a ghost’s presence or to declare Meredith’s collapse absolute. Is that closing shot the spectral echo of a child lost, or the last crack in a mother’s mind? By ambushing expectations of genre and narrative certainty, Mom poses questions instead of delivering answers—an invitation to reckon with what truly haunts us.

The Review

Mom

Mom unveils a chilling portrait of maternal fragility, where dread seeps from everyday spaces and unspoken fears. Hampshire’s fierce portrayal grounds the immersive atmosphere even as familiar horror tropes resurface. Though its narrative opacity may frustrate some, the lingering tension and ambiguous finale invite reflection on grief and identity. It’s a slow‑burn that reverberates long after the lights come up.

PROS

- Emily Hampshire’s raw, commanding performance

- Immersive atmosphere with meticulous sound design

- Striking cinematography that mirrors psychological decay

- Ambiguous narrative that sparks post‑viewing reflection

- Thoughtful exploration of postpartum depression

CONS

- Reliance on familiar horror tropes

- Deliberate pacing may test patience

- Narrative opacity can feel frustratingly opaque