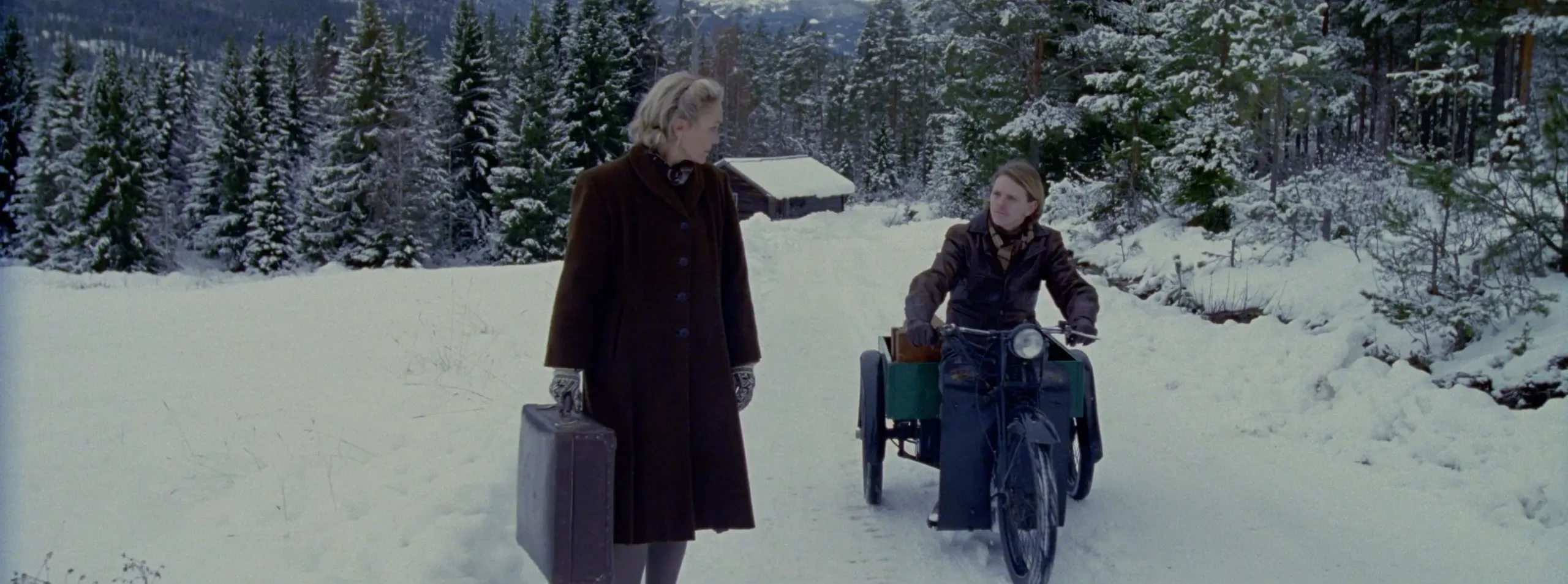

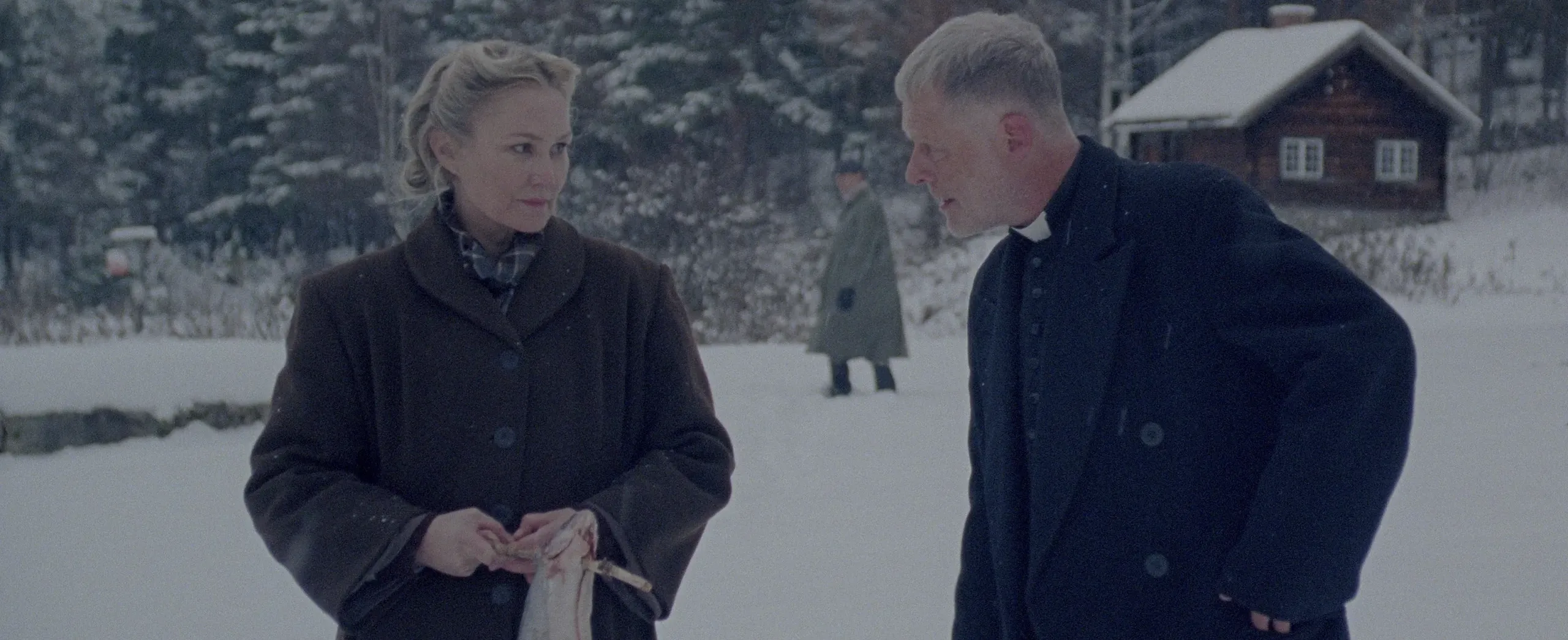

In a remote Norwegian village blanketed by snow, The Fishing Place unfolds as a study in quiet coercion. Anna, newly released from Nazi detention, arrives under the watchful eye of Officer Hansen. He tasks her with tending to—and reporting on—a Lutheran pastor whose sympathies he suspects lie with the resistance. Through this premise, the film opens its spy‑drama tableau without fanfare, inviting us into its sealed world.

Rob Tregenza returns after nearly four decades behind the camera for his fifth feature. As writer, director and cinematographer, he constructs each sequence as if it were a self‑contained essay in motion. Although this marks a shift from his contemporary setting in Gavagai, his fixation on extended crane and tracking shots remains. Those deliberate movements guide our attention, charting character interactions against stark landscapes and ornate interiors alike.

Rather than framing action as spectacle, Tregenza treats each long take as a narrative device. Conversations carry the heft of unspoken threats; gliding camera strokes underscore who holds power and who bears its weight. The film’s fusion of historical drama with a self‑aware climax hints at a deeper inquiry into storytelling itself. In this manner, The Fishing Place asks us to consider the gaze that records—and the moral cost of watching.

The Camera as Co‑Author: Aesthetic & Cinematography

Tregenza stakes his narrative claim with unbroken takes that unfold like breathing passages. The six‑minute household introduction doesn’t linger for spectacle—it charts every subtle glance and unspoken motive among Anna, Klaus and Hansen.

Later, a seven‑minute escape shot tracks Anna’s moral reckoning in real time, turning suspense into a spatial puzzle. The final 22‑minute sequence pulls back the curtain, revealing the rigging and crew. Here, the camera isn’t a passive recorder but an active presence, shaping our understanding of what lies within—and beyond—the frame.

Shot in an ultra‑widescreen ratio more than twice as wide as it is tall, the film contrasts sculptural fjords with claustrophobic interiors. In outdoor scenes, mountains and sea occupy equal narrative weight, suggesting that landscape carries its own judgments. Indoors, elongated rooms become stages for converging loyalties—Anna moving from one corner to another, her path circumscribed by furniture and portraits. Each composition feels deliberate, as if Tregenza measures character relationships by the negative space he leaves around them.

A winter palette of bleached whites and muted browns sets a quiet baseline. Moments of menace arrive in abrupt tonal shifts—a fishing trip bathed in bilious green, then scorched orange-red for an instant of violence. Natural light filters through frosted windows, lending a chilly realism to domestic scenes. When lamps glow in the drawing room, they cast long shadows that echo the characters’ inner divides. Light here isn’t decorative; it marks the thin line between exposure and concealment.

Absent musical cues, creaks of forest pines and rolling waves serve as off‑screen narrators. Dialogue is spare; each line feels freighted with consequence. Because edits are rare, silence deepens tension: we wait for footsteps, for a door to close, for an unseen threat to materialize. The result is a pacing that demands patience, yet rewards close attention—each ambient rustle becomes part of the story’s secret language.

Narrative Structure & Pacing

From its opening frame, a single six‑minute dolly shot serves as both welcome mat and warning sign. We glide through Klaus’s dining room, past Anna’s silent scrutiny and Hansen’s clipped orders, all without a single cut. That sequence functions like a miniature overture—each character’s position and posture foreshadows alliances and betrayals, and we learn more from what remains off‑camera than from spoken lines.

Once the stage is set, the story unfolds through discrete village encounters. A pastoral house visit here, a hushed whisper about the resistance there, even a tech‑minded engineer dropping “heavy water” as casually as village gossip. A crossfade between Anna and Hansen frays their power dynamic—she drifts in with uncertainty, he coalesces into sharper menace. These stroll‑through scenes feel episodic, yet they lock together in a chain of ever‑tightening tension.

With just under half the runtime left, the film veers into meta territory. The camera peels back to reveal its own crane arm, operators and all, as if to say: “Remember, this is a construction.” It’s an abrupt pivot from clandestine drama to workshop diary. That leap out of narrative disguise reframes our earlier trust in the lens, asking us to rethink every tracked step we’ve followed.

Tregenza alternates measured calm with sudden jolts of suspense. Long, contemplative takes let atmosphere settle like snow; gestures and glances gain weight. Then a burst of violence or a tense exchange snaps us awake. By letting thriller conventions simmer rather than boil, the film demonstrates that stillness can be as electric as gunfire.

Anchors of Emotion: Character & Performance

Anna’s presence is quiet yet unwavering. Petersen uses minimal dialogue to full effect—each pause and downward glance revealing the weight of her predicament. In scenes where she serves Klaus’s family, her measured movements betray a simmering resolve. That tight control of posture and expression turns Anna into a living cipher: you sense her loyalty shifting even when her face remains still.

Hansen wears the uniform with buttoned‑up courtesy, his manners more chilling than any shout. Winther’s crisp enunciation gives his speeches an unsettling clarity—every sentence stretches out, a reminder that language itself can be weaponized. When he smiles, you feel the potential for sudden violence lurking beneath. It’s a performance of ice‑cold discipline, one that underscores how totalitarian power thrives on rigid formality.

Lust brings a subdued warmth to the pastor’s crisis of faith. His clipped replies and tight jaw convey a man wrestling with doubt, yet those same concise turns of phrase hint at compassion. In his visits to villagers—comforting a dying actress or listening to reluctant confessions—he becomes a barometer of communal anxiety. The contrast between his calm voice and the landscape’s foreboding hush sharpens every moment he steps into frame.

Klaus and Margit embody the film’s domestic tension: his industrial ambitions clash with her moral unease, especially when heavy‑water talk breaks the surface like a hidden current. Resistance operatives appear in furtive glances and coded exchanges, their fleeting cameos reminding us how easily trust unravels. A young engineer’s offhand mention of “heavy water” lingers as prophecy, linking personal dramas to the broader shadow of technological fallout. Together, these performances weave a network of loyalties and betrayals that hold the story’s moral stakes in constant motion.

Patterns of Conflict and Reflection

Tregenza frames Anna’s coerced duty and the quiet defiance of villagers as moral chess. Anna’s forced allegiance to Officer Hansen and her covert sympathy for Pastor Adam create a landscape of “contradictory vows.” Rather than clear heroes and villains, we see lives squeezed between survival and conscience—an approach that recalls recent portrayals of gray‑zone loyalties in prestige television espionage dramas.

The camera itself feels like an occupying force. Characters enter frame almost on parade, their movements measured by an unseen authority. Off‑screen threats loom larger than any visible gun. This tactic echoes the creeping dread of series such as Mindhunter, where what you don’t see breeds deeper anxiety. Here, surveillance becomes a thematic muscle, flexed in every unbroken take.

Telemark’s fjords and ancient pines register more than scenery—they judge. Wide shots lodge characters against vast, silent terrain, suggesting that history presses in from all sides. When the camera tilts upward to crown the trees, their stoic presence feels complicit in witnessed atrocities. It’s a reminder that setting can function as a silent chorus, observing betrayal as keenly as any living character.

A seemingly casual line about “heavy water” tiptoes into nuclear‑age portent. This subplot ties personal dramas to epochal shifts, much as Homeland once threaded domestic scenes through global terror fears. The tension between pastoral quiet and industrial ambition underlines how scientific breakthroughs can yield both liberation and destruction.

The final reveal of the crane and crew ruptures narrative confidence. In that 22‑minute self‑exposure, Tregenza borrows from Brechtian theater to reframe every prior moment as constructed artifice. It’s a bold reminder that stories shape our view of history—and that questioning the storyteller’s gaze can be as vital as the tale itself.

Mapping Telemark’s Pulse

Telemark’s wartime resonance underlies every shot. This is the land where heavy‑water plants once stood—and where Vidkun Quisling hailed from—so the film’s choice of setting feels loaded rather than decorative. Rural roads and isolated homesteads withstand the weight of strategic occupation, reminding us that history often unfolds in quiet corners far from grand battlefields.

Winter’s grip turns landscape into a character of its own. Snow drapes trees and rooftops in monochrome silence; boats slip through tendrils of sea fog as if guided by memories. That biting cold becomes a constant reminder of danger, each exhaled breath marking both vulnerability and resolve.

Indoors, Tregenza contrasts spaces to mirror shifting loyalties. In Klaus’s art‑filled salon, polished surfaces and family portraits stage civility under strain. The village church’s bare pews and candlelight speak of faith tested by politics. Cramped living quarters, where whispers hover just beyond earshot, underscore how private lives fracture under surveillance.

Sound design stitches setting to story. Wind‑rustled pines tap out uneasy rhythms while distant church bells register time slipping under occupation. The creak of floorboards signals every step toward moral choice—sometimes louder than any gunshot. Here, atmosphere isn’t background; it edits the narrative, shaping our sense of what lies at stake.

Epilogue: Craft and Consequence

Tregenza’s formal daring serves the film’s ethical core: every unbroken take and purposeful camera glide turns technique into moral inquiry. Surveillance isn’t just a narrative tool—it becomes a question of complicity, inviting us to consider how the act of watching shapes our sense of right and wrong.

That tension extends beyond 1940s Norway. When Anna’s mission echoes through modern corridors of power, the film asks whether today’s data‑harvesting and algorithmic oversight mirror the same coercive impulses. The nod to “heavy water” feels less like period detail and more like a warning: technological progress can slip from promise into peril.

This work will resonate with cinephiles drawn to meditative pacing and investigations of form. Those who trace character arcs through camera movement will find each scene’s construction as compelling as the plot it carries. And while the abrupt self‑reflexive finale may unsettle viewers expecting a conventional thriller, it underscores that every story reveals as much about its maker as its subject.

More than a wartime drama, The Fishing Place stakes a claim in the lineage of filmmakers who probe history by scrutinizing their own craft—from Chris Marker’s essay films to Béla Tarr’s single‑take epics. It may not fill multiplexes, but it cements Rob Tregenza’s role as a filmmaker who frames the past to illuminate present concerns.

Full Credits

Director: Rob Tregenza

Writers: Rob Tregenza, Kirk Kjeldsen

Producers: Specific producer information is not listed in the available sources.

Cast: Ellen Dorrit Petersen (Anna), Andreas Lust (Priest), Frode Winther (Hansen), Eindride Eidsvold

The Review

The Fishing Place

The Fishing Place transforms patient, gliding camerawork into a study of moral tension, where each unbroken take deepens our investment in Anna’s impossible mission. Its deliberate pace and startling self‑reflexive turn may challenge genre expectations, but they reward viewers willing to engage with cinema’s power to question authority and complicity.

PROS

- Cinematography drives the story forward

- Performances convey quiet moral conflict

- Extended takes heighten immersion

- Atmosphere builds sustained tension

- Meta finale reframes earlier scenes

CONS

- Deliberate pacing may feel slow

- Middle section relies on episodic structure

- Self‑reflexive shift can be disorienting

- Supporting roles receive limited depth