Jan Dolski awakens to a silence that is louder than any explosion. He is the last man standing on an alien world after a disastrous landing, a premise that feels familiar yet is rendered with the profound, existential dread reminiscent of Stanisław Lem’s Solaris.

The planet itself is a canvas of stark beauty, its barren gray rocks streaked with the oily shimmer of unknown minerals. This is not a world teeming with monsters, but one defined by an immense and terrifying emptiness.

His only hope is a mobile base waiting on the horizon, a colossal wheel that evokes the iconography of Kubrick’s 2001. But this symbol of human ingenuity is useless to a single person. As a deadly sunrise begins to cook the horizon, creating a literal deadline, Jan is faced with a dilemma. He cannot pilot the vessel alone.

Onboard, a quantum computer and a strange resource called Rapidium offer a startling, radical solution. He can create alternate versions of himself, duplicates born from the moments in his life where a different choice would have forged a different man. To escape the inferno, Jan must shatter his singular identity into a committee of selves.

The Sum of All Fears: A Life Unraveled

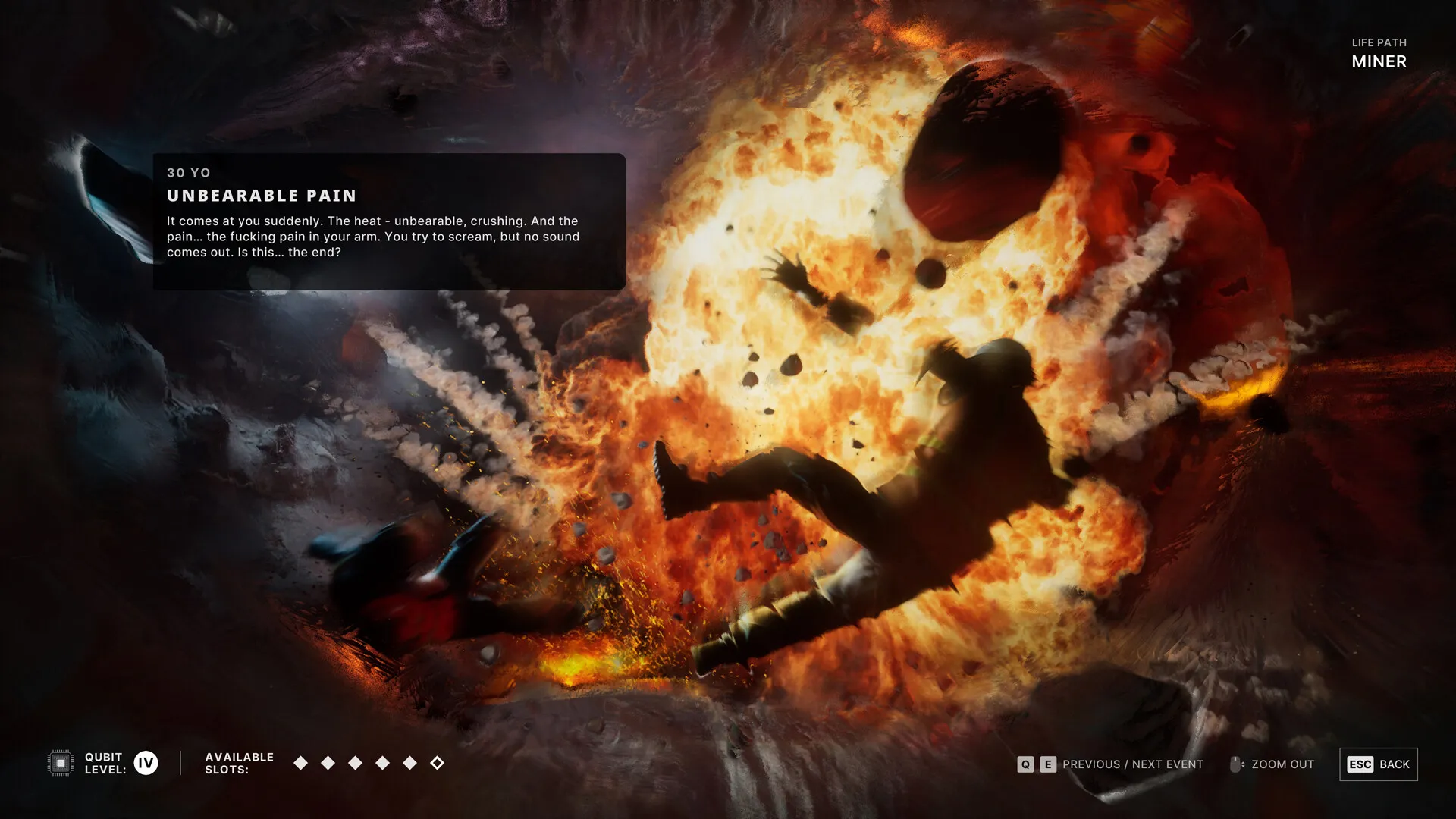

The game’s solution to Jan’s solitude is a brilliant piece of interactive theater. Using a quantum computer, the player performs a kind of digital psychoanalysis, sifting through the branching timeline of Jan’s life. This “Branching Procedure” visualizes his past as a neural map, where pivotal choices—going to university, leaving home, ending a relationship—are forks in the road.

It feels less like a character creator and more like navigating the fragmented memories in a film like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. By selecting a different path and spending the precious, mined resource of Rapidium, the player doesn’t just generate a clone; they give birth to a regret, a “what if” made flesh.

These are not identical copies. The performance by actor Alex Jordan is a masterclass in nuance, evoking the way Tatiana Maslany inhabited her many roles in Orphan Black. An Alter born from a life of manual labor is physically and vocally distinct from one who pursued academia.

The Jan who became a scientist has a different posture, a different cadence, a different sorrow than the Jan who became a botanist after following a lover to another country. This mechanical system powerfully argues that identity is not innate but an accumulation of experiences. Each Alter is a living testament to a path not taken, sharing a common history up to a point of divergence before becoming a stranger.

This crew of ‘you’ is essential for survival, with each Alter’s specialized skills needed to operate the base’s machinery. Yet the game denies any clean sense of wish-fulfillment. The moment an Alter awakens, they are confused, angry, and aware of their nature.

They are not grateful assistants but bewildered individuals ripped from their own lives, immediately confronting Jan with the profound ethical horror of his decision. They are people, yet they are also tools. This immediate tension transforms the gameplay from a simple management simulation into a complex negotiation with the resentful ghosts of your own past, each one demanding to be recognized as more than just a means to your survival.

The Domestic Machinery of Survival

The base itself is a marvel of thematic design, a colossal wheel rolling inexorably forward to escape a relentless sun. Inside this self-contained world, the perspective shifts to a 2.5D cross-section, turning the player into an observer of a human ant farm.

This directorial choice, seen in developer 11 bit studios’ own This War of Mine, creates a powerful sense of intimacy and distance. We are close enough to watch Jan traverse the halls and use the elevator, yet we are also looking at a diagram of a machine, a complex system of interlocking parts.

It is a home, but it is also a clockwork apparatus built for a single purpose: continued existence. This view perfectly captures the player’s conflicted role as both inhabitant and detached god, managing a crisis from just outside its emotional core.

Expanding this mobile habitat feels like solving a puzzle box. New rooms—dormitories, kitchens, laboratories—are slotted into the available space like Tetris blocks. The game makes a fascinating design choice here by removing much of the genre’s typical friction. Rooms appear instantly, and can be moved or deconstructed for a full refund at any time.

This is not the harsh, punishing survivalism of other titles where a wrong choice costs precious, irreplaceable materials. Instead, the challenge is one of pure logic and spatial efficiency. The system encourages experimentation, prioritizing the player’s engagement with its systems over the anxiety of permanent mistakes.

It does, however, create its own kind of dissonance; the freedom to constantly reconfigure your home can lead to a disorienting search for a room that was somewhere else just a moment ago, a small mechanical wrinkle that speaks to the difficulty of maintaining a sense of place while in constant motion.

This is where the game’s philosophical weight truly asserts itself. The resource management loop requires assigning the various Alters to their stations. Here, the emotionally complex individuals, born from deep-seated regrets, are functionally reduced to their skills. A man’s entire alternate life becomes a buff to production speed or a bonus to research output.

This is the game’s quiet tragedy, where the messy reality of human experience is converted into clean data for a production queue. Systems like the “uphold production” feature streamline the process, a clever automation that also pushes the player further into the role of a detached manager. Balancing the crew’s needs for rest and sustenance against the demands of the ticking clock is not just about filling meters; it is a constant mechanical expression of the core ethical dilemma: how much can you exploit yourself to save yourself?

Surveying the Alien Psyche

When Jan steps outside, the game’s language shifts. The detached, diagrammatic view of the base gives way to a vulnerable, over-the-shoulder perspective that grounds him in a vast, alien landscape. The environments here feel drawn from the tradition of cerebral science fiction cinema, less like a playground of obstacles and more like the sentient, enigmatic “Zone” in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker.

Exploring the dramatic canyons and strange caverns is not about conquest, but about intrusion. The primary goal is to find resources to feed the ever-moving base, but each excursion is tinged with the feeling that you are a trespasser on a world that is quietly observing you.

The tools of survival reflect a very human desire to impose order on this chaos. Laying down a network of pylons to connect a mining rig to the base is a satisfying act of drawing lines, of creating a logical grid on an illogical surface. It is industrialization in miniature. Even the process of finding resources, a minigame of placing probes to survey beneath the ground, feels like a deliberate chore.

This mechanical friction makes the act of discovery feel like genuine labor, grounding the fantastical setting in a tactile reality. Unlocking new tools like grapples or rock vaporizers follows a familiar pattern of technological progression, yet this growing mastery feels tenuous against the planet’s immense and inscrutable scale.

The planet’s hostility is rarely straightforward. Instead of creature combat, the threats are environmental and almost spectral. Translucent, radioactive anomalies drift through the landscape, their cores needing to be zapped with a tool that feels like it was borrowed from the set of Ghostbusters. This lighthearted interaction creates a curious contrast with the eerie, almost paranormal nature of the hazard.

Larger threats, like magnetic storms that recall the blizzards of Frostpunk, serve a clear narrative purpose. They immobilize the base and make venturing outside impossible, forcing the player’s attention back inside to the simmering human drama. The planet does not just try to kill Jan; it actively conspires to lock him in a room with himself.

The Parliament of the Self

The survival mechanics are merely the stage for the game’s true purpose: a deep, unrelenting interrogation of the self. This is where the Polish studio’s lineage is most apparent, trading the grand scale of galactic war for the intense, often melancholic interiority that marks its previous work.

The central conflict is not with the alien planet, but with the landscape of one’s own history. The Alters serve as living embodiments of regret and possibility, forcing Jan to confront the men he could have been. It is a playable thought experiment on identity, arguing that we are defined as much by the paths we abandoned as by the one we walk.

This psychological drama unfolds through a sophisticated social simulation. Managing the Alters means navigating their individual traumas and desires, which are extensions of Jan’s own. The game presents genuinely complex moral quandaries that resist simple solutions. An Alter who comes from a timeline where he saved his marriage to Lena begs to speak with her on Jan’s behalf; a Jan who stood up to their abusive father resents the original for his cowardice.

These moments transform the player from a base manager into a therapist and mediator for a fractured psyche. Dialogue choices carry immense weight, with the potential to push an Alter toward a mental breakdown or even permanent death. The stakes are not about winning or losing, but about how one chooses to live with the consequences of their past.

The story is delivered in a clear, episodic structure of acts, each presenting a new location and a central crisis that must be resolved to proceed. This framework provides narrative punctuation to the constant cycle of survival.

Beneath the personal drama, a wider plot involving the faceless “Ally Corp” adds a layer of systemic critique, framing Jan’s personal hell as a symptom of corporate exploitation. This ensures his journey is not purely solipsistic. The self is not an island, and the choices that lead to one of several endings are influenced by both the intimate dialogues in the base and the oppressive presence on the other end of the comms link.

An Audiovisual Echo Chamber

The game’s presentation is a study in purposeful contrast. Outside, the alien world is a breathtaking, painterly vista of desolation. Inside the wheel, the view becomes a clinical, detailed diagram of a life in crisis. This visual language is remarkably effective, underscoring the tension between external agoraphobia and internal claustrophobia.

The decision to render certain key story moments as voiced-over storyboards feels less like a budgetary constraint and more like a choice from the playbook of independent animation. It focuses the player’s attention squarely on the weight of the words and the nuance of the vocal performances.

The soundscape completes this atmosphere of isolation. The musical score, with its clear nods to 1980s synth-driven science fiction, evokes a specific mood of thoughtful, melancholic wonder. It is the audio, however, where the game’s heart lies. Alex Jordan’s phenomenal performance as every Jan is the central pillar holding the entire experience aloft. Each voice is a distinct personality, a unique frequency in a chorus of one.

The Review

The Alters

The Alters is a rare and intelligent work, a survival game where the greatest challenge is navigating the landscape of one's own past. It masterfully uses its management and exploration systems not as endpoints, but as conduits for a profound, cinematic story about identity and regret. While minor mechanical frictions exist, they do little to detract from its core achievement: a deeply human, thought-provoking experience anchored by a remarkable central performance. It succeeds as a testament to how interactive storytelling can explore the most complex corners of the human condition.

PROS

- A deeply resonant story exploring identity and choice.

- Brilliant central performance by a single actor embodying multiple characters.

- Meaningful fusion of survival mechanics and narrative themes.

- Strong, atmospheric audiovisual presentation.

CONS

- Resource scanning minigame can feel like a chore.

- Navigating the modular base may become confusing at times.