AUM: The Cult at the End of the World throws viewers into a maelstrom of gas-filled subway cars and frantic radio dispatches (an arresting choice, since most docs ease you in). On March 20, 1995, sarin gas tore through Tokyo’s Hibiya Line, killing 13 and injuring thousands.

Ben Braun and Chiaki Yanagimoto follow that calamity back to its source: Shoko Asahara’s Aum Shinrikyo, which mutated from a meditation circle into a doomsday machine. Premiering at Sundance, the film asks: How did a fringe yoga outfit morph into a global terror network?

And why did its excesses go unchecked for so long? (Hint: blinking often helps when history feels stranger than fiction.) By probing those questions, the documentary reckons with faith’s dark mirror—and whether vigilance can ever catch up to conviction.

Origins and Organizational Evolution

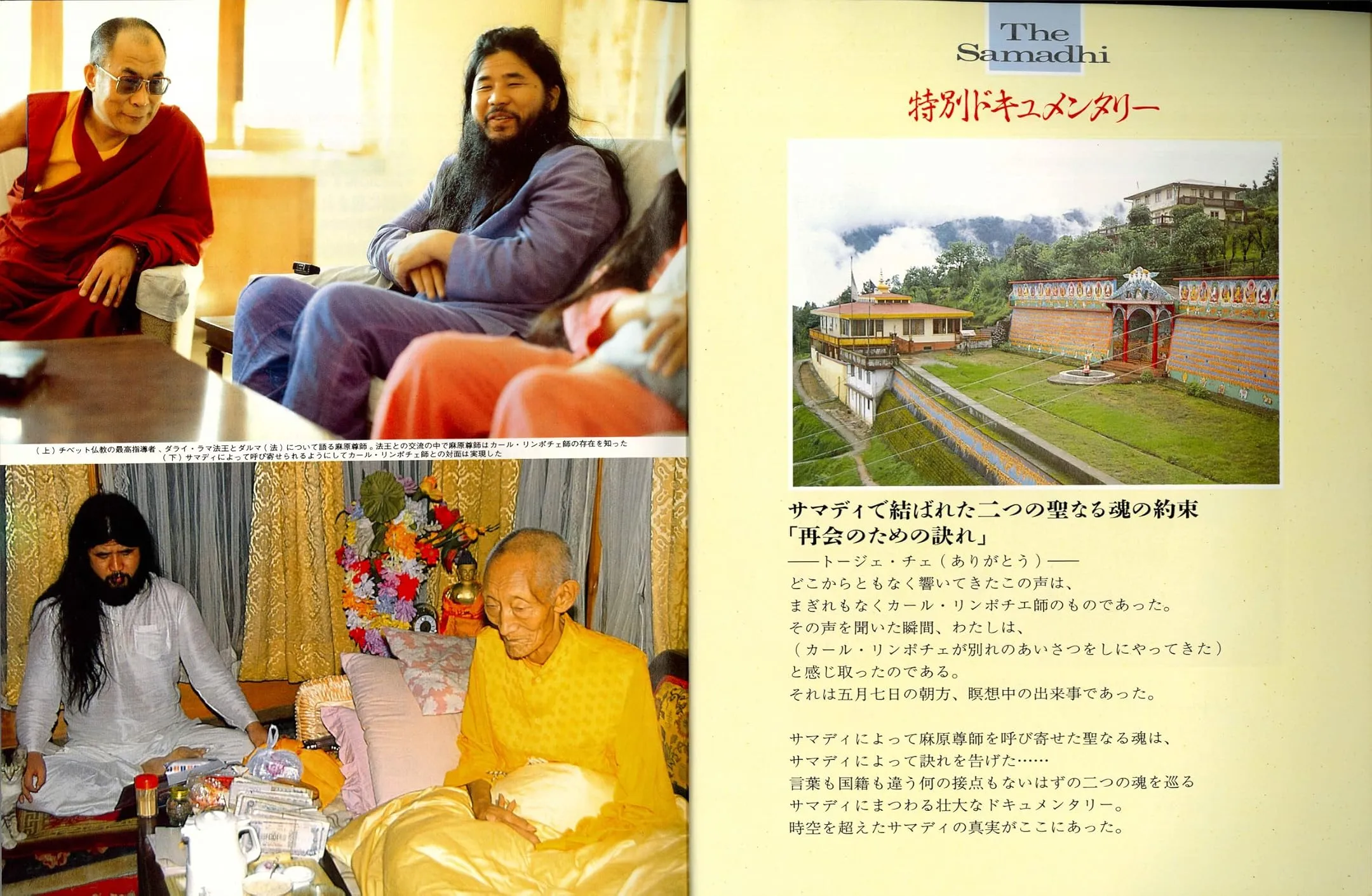

Shoko Asahara began life as Chizuo Matsumoto: a near-blind graduate of unaccredited pharmacy courses who moonlighted as a yoga instructor. In 1984 he launched Aum Shinrikyo, promising “miracle” meditations and purported cures (the term “therapeutic cult” might apply). Official registration in 1989 gave the group legal cover—an entry ticket to Japanese society.

Televised “levitation” stunts and slick promotional anime drew in university students seeking meaning amid post-bubble malaise. When Asahara’s 1990 bid for parliamentary seats crashed, he repackaged the cult as a political contender—a pivot that eventually flopped.

Yet geopolitical shifts offered fresh leverage: after the Soviet collapse, Aum forged ties in Russia, securing chemical-weapons know-how and even small arms. That expansion—from incense-lit ashrams to clandestine factories—illustrates a pathology of ambition: belief harvested as biochemical weaponry.

The 1995 Subway Attack and Personal Stories

The film’s in medias res opening flings us onto a train carriage where dispatch recordings crackle beside bleary surveillance footage. At 8:09 AM, sarin canisters hiss open; 13 commuters die, thousands gasp for air. Rather than abstract statistics, Braun and Yanagimoto humanize calamity through intimate portraits.

Yoshiyuki Kono, scapegoated after a Matsumoto-test run accident, lost family and reputation. Tsutsumi Sakamoto, a lawyer who prosecuted Aum, vanished along with his wife and infant son—victims of karmic retribution turned lethal. Oxygen-tubed survivors appear, their gratitude tinged with survivor’s guilt (medicine meets metaphysics here).

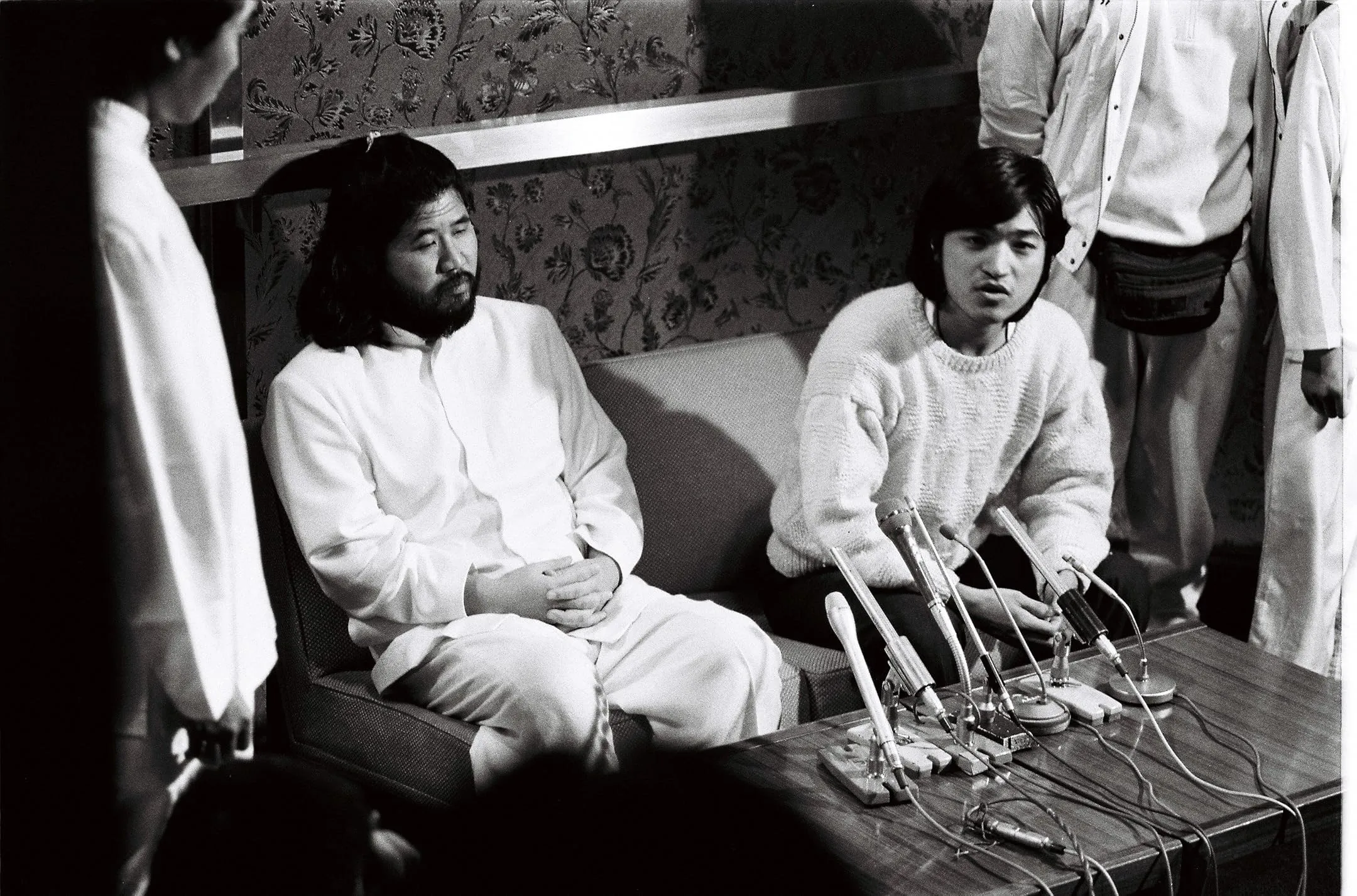

Fumihiro Joyu, once Asahara’s gilted PR manager, surfaces as marquee interviewee. Now leading Aum’s splinter group, he speaks in soothing tones yet refuses any self-reflection; his “most-hated man in Japan” claim lands flat (one term for it: “vanity denial”).

Curiously, few frontline survivors recount their own terror—an omission the filmmakers gloss over. And while we glimpse the Russia connection, its full scope remains compartmentalized behind bureaucratic barricades. In these gaps, the film reveals its own blind spots: a cult-story told through selective lenses.

Documentary Craft, Themes, and Contemporary Resonance

Clocking in at 106 minutes, AUM attempts encyclopedic reach where a miniseries might thrive. Archival news clips segue into animated re-creations (a clever riff on propaganda tropes), while talking heads shuffle on and off screen like chess pieces.

Journalists Marshall and Kaplan provide spade-work context; ex-members and victims supply emotional ballast. Notably absent are law-enforcement insiders, whose silence invites questions about institutional accountability.

Moments of genuine clarity emerge when media complicity is laid bare: TV producers chasing ratings handed Asahara free airtime, unwittingly grooming a bio-terrorist celebrity. Yet the film’s pacing sometimes feels “grab-and-go”—racing past revelations that deserve lingering. The score’s muted tension underscores this ambivalence, alternating empathy with clinical detachment.

Symbolically, AUM resonates as a case study in “belief contagion,” a term worth coining. When charismatic authority meets social fracture, ideas can become invisible pathogens. In a world buffeted by shifting convictions—political, religious or digital—the film reminds us that unchecked faith can mutate into mass destruction. If history is a mirror, AUM demands we stare back.

AUM: The Cult at the End of the World premiered at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival and was released in select U.S. theaters on March 19, 2025, followed by a digital release on March 28, 2025.

Full Credits

Directors: Ben Braun, Chiaki Yanagimoto

Writers: Ben Braun, Chiaki Yanagimoto

Producers: Ben Braun, Chiaki Yanagimoto, Dan Braun, Josh Braun, Rick Brookwell

Cast: Shoko Asahara (archive footage)

Director of Photography (Cinematographer): Yohei Tateishi

Editor: Keita Ideno

Composers: Dan Braun, Charlie Braun

The Review

Aum: The Cult At The End Of The World

AUM: The Cult at the End of the World offers a compelling, if uneven, exploration of faith weaponized. Its vivid archival footage and thematic urgency illuminate how charismatic authority can morph into mass terror, even as sourcing gaps and brisk pacing leave some facets underexamined.

PROS

- Vivid archival footage that immerses viewers in 1990s Tokyo

- Thought-provoking access to former members and victims

- Creative use of animation to illustrate propaganda tactics

- Sharp exploration of media complicity and institutional failures

- Philosophical framing of belief as a “contagion”

CONS

- Key survivor testimonies are underrepresented

- Law-enforcement perspectives largely absent

- Russia–cult connection remains only partially illuminated

- Pacing rushes through certain revelations

- Central interviewee offers little introspection