In “Meat,” Dimitris Nakos presents a gruesome look at familial breakdown and moral decay in the setting of a butcher shop (the irony is obvious). This first feature played at festivals like Toronto and Thessaloniki, invites viewers to witness the raw interaction of power and dependence simmering beneath the surface of everyday life. It is set against the backdrop of a small Greek village.

The movie starts with a real slaughterhouse, immersing us in a world where life and death dance together in a horrifying dance. This isn’t just a story about a butcher; it’s a modern Greek tragedy in which societal standards and family responsibilities have replaced the gods. When it premiered at the 46th Cinemed Festival, the film received praise for its daring photography, which was frequently frantic and hyperactive, much like the chaos of the characters’ lives.

The meat trade represents both sustenance and destruction in Nakos’s reflection of our familial structures, making distinguishing between love and duty difficult.

Narrative Structure and Themes: A Modern Greek Tragedy

Each scene in “Meat” feels like a carefully planned fall into chaos, giving the story the dramatic flair of a Greek tragedy. Takis, the patriarch, is seen getting ready for the grand reopening of his butcher shop, which serves as both a metaphor and a real blood bath and sets the stage for familial conflict. This isn’t just a business deal; it’s a battlefield for unresolved resentments and power struggles.

The story goes from mundane to tragic in an instant when his son Pavlos, who feels like he is being watched, commits an impulsive act of violence against a neighbor. We’re in the realm of everyday life one minute and struggling with the weight of guilt and complicity the next.

The movie skillfully handles family conflict and moral conundrum themes, showing how love and anger are frequently intertwined. There is a toxic mix of patriarchal authority and emotional trickery in Takis’s family because of his controlling presence. The dialogue, full of hidden meanings, perfectly describes how familial relationships can go back and forth between affection and hostility. It’s as if Nakos coined the phrase “patriarchal paradox” to describe how both love and hatred at the same time characterize these relationships.

In addition, “Meat” resonates with modern societal problems, reflecting on corruption and the loss of moral principles in a world that is becoming more and more materialistic. The characters’ desperate efforts to keep their status (and sanity) reflect larger themes that have been present throughout history, from the struggles of ancient Greece to the struggles of today’s societal structures.

Viewers are forced to confront the cyclical nature of violence and familial duty in the movie’s conclusion, steeped in Aristotelian redemption. This raises the question of whether or not a person can ever truly escape the weight of their history.

Throughout this complex story, Nakos encourages us to look beneath the surface layers of familial love and societal expectations to find the dark truths beneath. This powerful lesson teaches us that the past is always close at hand.

Character Analysis: The Weight of Blood and Betrayal

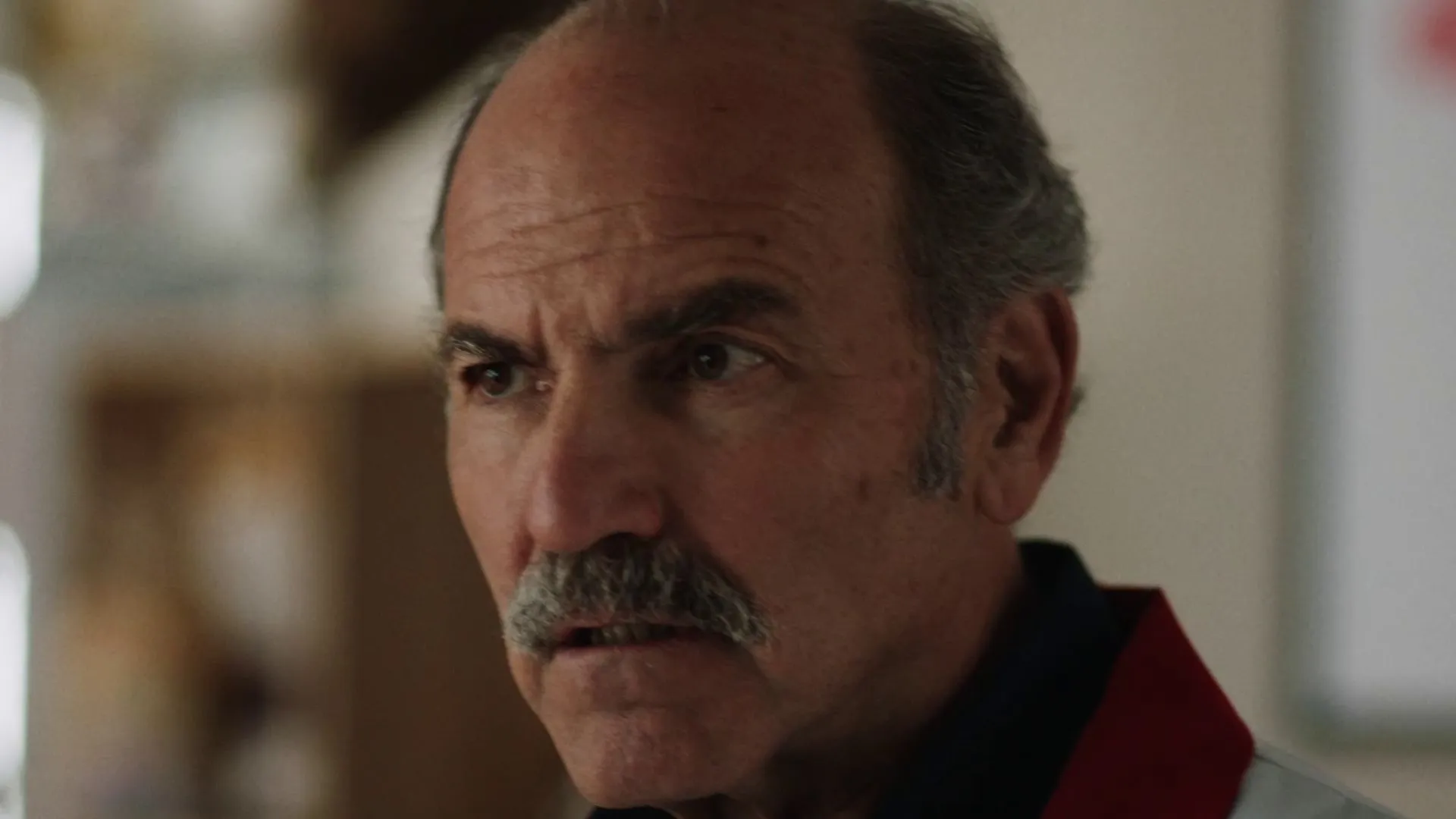

Takis, the family patriarch, is central to “Meat.” Just being around him feels like a dark cloud over his family. His portrayal by Akyllas Karazisis gives him a powerful but deeply flawed charisma, making him a perfect example of the controlling father who holds on to old ideas of what it means to be a man and of authority.

Takis desperately wants to be liked by others, and he does this through his butcher shop, which is a fake success built on the blood of animals and family loyalty. They become estranged due to his dislike for weakness, which he sees in his son Pavlos, creating tension that builds throughout the movie. The father’s insecurities show up as harsh demands for his children. This is a classic example of the “patriarchal burden.”

There is a lot of unsaid anger between the father and son in this situation. Pavlos, played by Iordanopoulos, oscillates between wanting to be liked and having a growing sense of anger. The violent act he did against their friend was the last straw in his desperate plea for attention. He seems stuck in a condition called “father’s shadow syndrome,” in which his father’s strict ideas stop him from reaching his goals. Pavlos is a live example of how patriarchal authority has failed, and one could say that he is the product of Takis’ toxic legacy.

Then there’s Christos, the Albanian boy who grew up with Pavlos. To this familial scene, his character adds depth. Christos stands between family and otherness, allowing us to see the complexities of loyalty and betrayal through his eyes. His relationship with Pavlos is competitive and brotherly, reflecting the complex dynamics of village community ties. Christos feels a sense of entrapment despite his sincere thanks to Takis and his complicity in his actions. We witness a moving story of loyalty put to the test by moral conundrums as he deals with the effects of Pavlos’s actions.

The interactions between these three characters—Takis, Pavlos, and Christos—reflect larger societal problems, especially the poisonous relics of patriarchal structures and the troubled relationships that develop within them. Nakos catches this tension beautifully, allowing us to question the very basis of family loyalty. By doing this, he makes us think about how societal expectations can change human relationships and leave emotional scars that last long after the blood has dried.

Cinematography and Direction: The Dance of Chaos and Control

The visual style of “Meat” oscillates between quick handheld shots and moments of complete stillness, creating a palpable tension that reflects the film’s thematic undercurrents. Giorgos Valsamis, the director of photography, uses a camera that moves quickly through scenes, weaving through them like a rabbit that has been spooked.

This choice was made on purpose to give the story a fast-paced feel while immersing the audience in the chaos surrounding Takis and his family. One could argue, though, that this method might make people sick, which is ironic since the movie is about violent upheaval.

The handheld shots do two things: they make the familial conflict seem more real and separate the audience from the characters’ emotional turmoil. It’s as if Nakos has coined a new term—”emotional vertigo”—to describe the disorientation experienced when one is thrown into such rocky exchanges. On the other hand, the static shots provide a brief break, allowing the weight of the characters’ efforts to settle. These breaks aren’t just for breaths; they’re stark reminders of the terrible things that will happen because of what they did, which adds to the sad tone of the movie.

Nakos’s choices as a director strengthen the story’s emotional tension. His choice to let scenes simmer instead of boil over creates a slow burn that makes viewers care more about how bad things are for the family. Every glance, every pause, is like a note in a dreadful Symphony. In the spaces between words, there is sharp dialogue that is often unspoken, compelling the audience to connect actively with the subtext.

The movie’s setting, a microcosm of rural Greece, also plays a role as a character. A backdrop for investigating societal norms and corruption is the intertwining of scenery and story. Through this lens, Nakos criticizes modern Greek life and considers global themes of blood loyalty, power, and the often violent costs of familial duty. The direction, steeped in irony and dark humor, begs viewers to consider the absurdities of everyday life, where the mundane frequently hide the monstrous.

Through its complex dance of chaos and control, “Meat” becomes a deeply felt commentary on the human condition, leaving us to deal with the disturbing truths that stay long after the movie ends.

Performances: Flesh and Blood on the Stage

The acts of Akyllas Karazisis and Kostas Nikouli make “Meat” a better movie by adding tension and emotional depth to the weaving. When Karazisis plays Takis, he embodies the archetypal patriarch; his performance is a masterpiece in ominous authority.

The weight of familial expectations and the suffocating grip of traditional manhood are perfectly encapsulated in every wrinkle in his brow and clipped tone. One could almost feel the anger in his eyes as if he were acknowledging the violence simmering beneath the surface (you could even call it a “stoic fury”). His performance is unsettlingly magnetic, luring viewers into his moral problems and turning them off with his bad morals.

Kostas Nikouli’s layered performance as Christos, the Albanian outsider, captures the complexities of loyalty and belonging and is equally compelling. In presenting a character torn apart by familial duty and societal prejudice, Nikouli skillfully balances vulnerability and subtly power. He has great chemistry with Karazisis, and the way they trade blows is a dance of power that keeps the audience on edge. Their connection has a lot of tension; it’s a brotherly bond that could be broken at any time.

This dynamic adds much to the film’s depth by allowing viewers to examine the complicated reasons behind their actions. When Takis tries to change Pavlos into someone like him, his interactions with Christos show where his authority is weak. The emotional weight of their acts deeply resonates with us, making us question the definition of family and loyalty. Nakos’s characters are more than just stereotypes because of how well they are portrayed; they become haunting reflections of the societal flaws that make them appear.

In this dark drama, every glance and movement carries the weight of history—a sobering warning that in the realm of love, love, and violence frequently share the same bloodline.

Sound and Score: The Unseen Pulse of “Meat”

The music for “Meat,” written by composer Dimitris Kouroupos, becomes a haunting background that fits perfectly with the story. The music goes up and down, often reflecting how people feel.

It oscillates between dissonant strings that evoke a sense of approaching doom and softer, poignant melodies that hint at brief moments of tenderness (if one can call them that in such a gloomy context). This sound world becomes a character in and of itself, controlling how the viewer feels almost surgically.

The sound design also has a noticeable effect. Every sound raises the stakes, from the butcher shop’s guttural sounds (meat cleavers cutting through flesh, blood splattering against cold floors) to the village’s background noise. Silence is interspersed with the din of violence in key scenes, creating a startling contrast that heightens the tension. This clever use of sound can be seen as a microcosm of the chaos in the characters’ lives, a mess that resonates with the audience long after the credits roll.

The soundscape challenges viewers to confront the discomfort of familial ties and societal expectations as Nakos constructs a story steeped in the macabre. Remember that in the “Meat” world, silence can be as loud as a butcher’s blade.

Social Commentary: The Butcher’s Knife of Society

“Meat” works on many levels and makes a sharp (no pun meant) comment on modern Greek society. The film’s central theme is the age-old conundrum of familial loyalty and corruption, which resonates strongly in a nation still dealing with the effects of economic and political turmoil. Takis holds on to his butcher shop as a sign of his status and power.

It’s a microcosm of society where selfish goals often precede moral ones. In the face of societal decay, the butcher’s trade becomes a metaphor for the moral compromises people make. You could even call it a “meat grinder of ethics.”

It makes fun of societal norms, especially those related to being a man and having authority. Takis’s controlling personality reflects a larger cultural archetype: the rigidly traditional patriarchal figure who stops growth and encourages hostility. While Pavlos is both a product of his father’s expectations and a victim of societal pressures to fit in, Nakos cleverly contrasts these two ideas.

The movie also shows how weak social bonds can be when people face their ambitions. As the outsider, Christos represents how unstable loyalty can be; his trip shows how societal norms can become a sword that cuts both ways. What do we pay for loyalty in a world full of corruption? That’s a good question that the movie raises.

Nakos forces viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about the human condition in this dark scene. He encourages confrontation with the darker urges that often lie beneath the surface of familial affection. A global audience is invited to consider the universal struggles of power, loyalty, and moral ambiguity, as the consequences go beyond Greece.

The Review

Meat

"Meat" is a visceral study of familial authority and moral decay, expertly weaving together loyalty and societal corruption themes. With powerful acting and a haunting score, Nakos creates a story that stays with you long after you see it. The movie's dark tone may not be for everyone, but it's a powerful look at the complexities of relationships and what it costs to be ambitious. Making it a compelling, if uncomfortable, cinematic experience forces viewers to confront their complicity in societal norms.

PROS

- Powerful performances, particularly by Akyllas Karazisis and Kostas Nikouli

- Engaging and thought-provoking themes surrounding family dynamics and societal issues

- Effective use of cinematography and sound design to enhance emotional impact

- Strong character development that invites deep reflection

CONS

- Bleak and unrelenting tone may deter some viewers

- Pacing can feel slow in parts, potentially losing audience engagement

- The moral ambiguity may leave some viewers unsettled or confused