It appears we are, once again, at one of those junctures where the wallpaper of civilization is peeling to reveal some rather unfortunate structural issues. Félix Dufour-Laperrière’s animated contemplation, “Death Does Not Exist,” doesn’t so much knock on this particular door as observe it sagely from across a chasm of palpable despair, one filled with the low hum of eco-anxiety and the sharp stink of inequity – our constant companions these days (and arguably most other days, if history hums a true tune).

That it chooses the often-ghettoized medium of animation to unpack these existential steamer trunks is its first, quiet act of rebellion. This is not your Saturday morning distraction, unless your Saturday mornings involve considering the precise weight of a soul before your second coffee.

Into this lovingly rendered gloom steps a cadre of earnest young firebrands, activists (or are they merely architects of a more theatrical form of despair?) intent on delivering a rather violent message to the so-called ‘figures of the establishment.’ Amongst them, Hélène, our protagonist, already seems to be wrestling with the pre-emptive ghosts of an action yet to be taken, her convictions perhaps a size too large for her comfort, or her stomach.

The air is thick with the unspoken; the film lays its cards on the table with an unnerving calm from its initial frames. This will be a serious business, a dive into the messy, uncomfortable spaces where idealism meets the often-brutal mechanics of attempted change. The gravity is immediate.

The Beautiful, Doomed Gesture

These aren’t your granddad’s placard-wavers, though the ancestral DNA of protest certainly pulses within their digitally-rendered veins. This particular cell of aggrieved youth operates with a potent cocktail of righteous fury and that uniquely modern strain of eschatological impatience, their sights set on the monolithic ‘establishment,’ embodied by some suitably wealthy (and presumably wicked) oppressors. Manon, their de facto drill sergeant of dialectics, proclaims with the kind of certainty only the truly committed (or perhaps truly mistaken, the line is famously thin) can muster: “All it takes is a bit of courage. It will all collapse.” One almost wishes it were that simple. Their desperate hope is for a spark, a single violent act to ignite a cleansing fire – a sort of societal CPR, administered with, in this case, rather archaic double-barrelled rifles. Beneath the bravado, of course, a discernible tremor of ‘what-on-earth-are-we-actually-doing’ fear ripples through them.

The stage for their grand, ill-fated gesture is an opulent mansion, a glass-and-guilt palace starkly contrasted against the encroaching wilderness – a visual shorthand for pretty much every societal imbalance we’ve been wringing our collective hands over since Rousseau (or thereabouts, historical precision isn’t the point here). When the bullets finally fly, it’s a strangely beautiful, yet horrific affair.

The blood that spews isn’t the familiar crimson; instead, it’s an unsettling yellow, or perhaps a sickly caramel – a chromatic choice that yanks the violence out of the purely visceral and into the realm of the disturbingly allegorical. Is it gold? Bile? The very colour of shattered illusions? Regardless, the revolution, as it so often does, eats its children with alarming alacrity. Marc, the whisper of a potential love story, is silenced among them.

And Hélène, our would-be warrior-poet? She freezes. A deer caught in the blinding headlights of ideological commitment meeting brute, unyielding reality. The body, it seems, possesses a more robust self-preservation instinct than the most fiercely held abstract belief when cold steel enters the equation. She runs, a blur of terror and abruptly orphaned ideals, fleeing into the woods, possibly wounded, definitely broken.

A Dark Night of the Soul, With Talking Ghosts (Possibly)

The forest Hélène stumbles into is less arboreal sanctuary, more an externalized map of her fractured psyche – a kind of psycho-geography where every rustling leaf whispers an accusation and shadows morph into fear-dictated shapes. Here the real reckoning (is there a difference from a journey, ultimately?) begins. She’s not alone for long. Enter Manon, or her remarkably chatty spectre – a post-mortem mentor, a classically rendered guilt-ghost, or perhaps Hélène’s own strident ideology talking back in a familiar, hectoring voice?

The film wisely lets us stew in that ambiguity. Manon offers a “second chance,” a concept as loaded as their disastrous foray into revolutionary praxis. Their exchanges, in landscapes unbound from boring old Newtonian physics, are a recursive Socratic method under extreme duress, circling loyalty, responsibility, and the sour aftertaste of fear. If the dialogue occasionally loops, isn’t that the nature of trauma’s faulty internal gramophone, stuck on the most painful groove?

The film itself shrugs with an almost Gallic indifference at labelling Hélène’s state. Dreaming? Dying? Enjoying a full-blown “nervous breakthrough” (a more poetic, if clinically dubious, term than its blunter cousin, “breakdown”)? The ambiguity is the point, immersing us in a liminal space where such distinctions lose terrestrial purchase.

This sylvan purgatory, an “ideological ICU,” coughs up symbols like an enthusiastic Freudian hairball: a young girl who might be Hélène Prime, a glimpse of past innocence or a future self judging her; pursuits both chillingly real and starkly allegorical; and a memorable, pastoral-gone-wrong vignette of a sheep, business-like coyotes, and an impromptu, casual resurrection. Nature here is not just red in tooth and claw but also hits the existential rewind button. Time, in this bewitched woodland, stretches and snaps like old elastic, memory and hallucination waltzing with disturbing intimacy.

This, then, is Hélène’s crucible, where comforting theories go to die. The simplistic binary of cowardice versus self-preservation gets a thorough, painful, necessary workout. Her neatly packaged beliefs about righteous violence have sprung significant, gushing leaks. Amidst the phantasmagoria, poignant introspection surfaces – the ghost of a future with Marc, the allure of a “boring” existence now shimmering like a distant, impossible paradise. The film doesn’t just show Hélène’s struggle; it rather impolitely maroons us inside her head – a disorienting, sometimes claustrophobic, but undeniably potent viewpoint. You are not merely an observer; you are a co-habitant of her spiralling consciousness, left to ponder if you’d fare any better.

Animated Anxieties: A Palette of the Psyche

This is animation that wears its handcrafted heart on its sleeve, each painstakingly rendered two-dimensional frame a defiant stand against the often sterile slickness of its digital brethren. The film’s “mystical and grounded” aesthetic, where one might occasionally glimpse the phantom caress of a brushstroke (or its digital equivalent, the effect is what matters), means a deceptively simple line can carry the weight of a philosophical treatise.

Hélène and her cohort are not mere figures in a landscape; they are porous, at times seeming to absorb the very chroma of their surroundings. The departed Manon and Marc, by contrast, often manifest as beautifully unsettling ectoplasmic outlines – less characters in the traditional sense, more resonant echoes against the backdrop of Hélène’s unravelling world, further blurring the already thin membrane between solid being and shifting backdrop.

The palette is a mood ring for the soul, a carefully curated visual lexicon designed to articulate the unspoken. Reds and blacks scream of trauma and the visceral, fragmented memory of violence; earthy greens and beiges whisper of Hélène’s fragile, evolving connection to the natural world (or what remains of it, anyway). Manon, in her spectral fury and unwavering conviction, often bathes in a coppery, almost infernal glow, a stark visual counterpoint to the porcelain sterility emanating from the establishment’s ivory tower.

And that infamous yellow blood – an inspired, jarring stroke of defiance against visual cliché, turning every gunshot into an aesthetic question mark as much as a narrative punctuation. These are not just pretty pictures, mind you; they’re emotional weather reports, guiding us through Hélène’s internal tempests with deft shifts in hue and a dramatic play of light and shadow that feels almost Rembrandtesque at times, if Rembrandt had been an anxious 21st-century animator with a penchant for existential dread.

Symbolism, naturally, is baked into the very pigment. The lush, almost aggressively textured wilderness – you can practically smell the damp earth and decaying leaves – fights a constant visual battle with the manicured, sterile opulence of the oppressors (no prizes for guessing where the film’s sympathies lie; hint: it’s with the dirt and the trees, not the gilded cages).

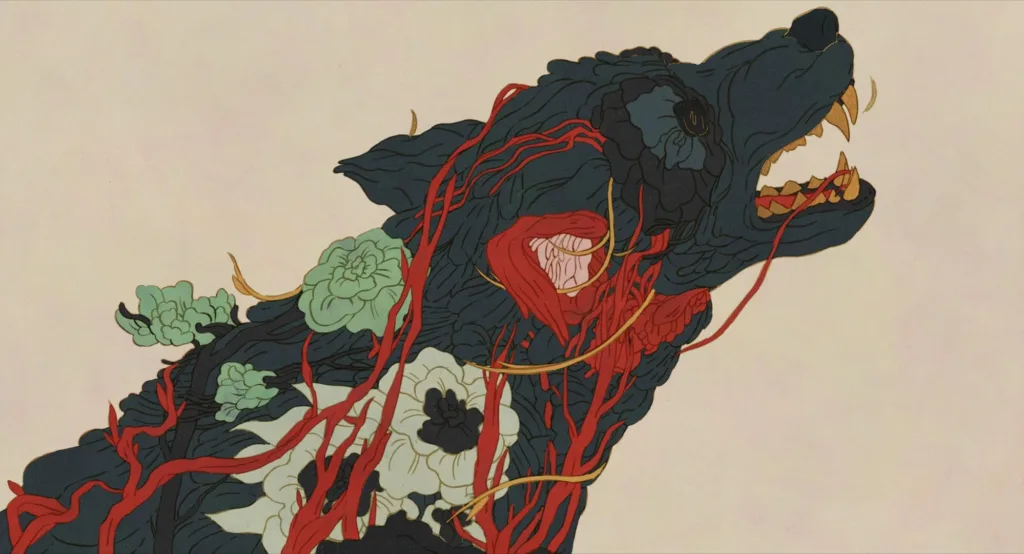

Those golden statues, first seen gleaming in the antagonists’ palatial grounds, act as silent, smirking commentators throughout – wolves, sheep, the whole allegorical menagerie, their fixed forms a mockery of the fluid, messy lives unfolding around them. A literal tidal wave of rewilding earth doesn’t just suggest societal upheaval; it positively bellows it from the screen in a moment of breathtaking, terrifying transformation. Even the acts of violence, stylized as they are, retain a visceral punch, a painterly brutality.

And those “cosmic flower-covered animal cadavers,” imagery straight out of some beautiful, eco-goth nightmare, hint at a cycle of decay and startling regeneration that’s both deeply unsettling and, perversely, shot through with a strange, almost alien kind of hope. The entire visual grammar conspires to create this sustained, oneiric hum, making the film less a narrative to be passively followed and more a psychic state to be inhabited, where reality frays at the edges and all established boundaries seem like mere, flimsy suggestions.

Animated Anxieties: A Palette of the Psyche

This is animation that wears its handcrafted heart on its sleeve, each painstakingly rendered two-dimensional frame a defiant stand against the often sterile slickness of its digital brethren. The film’s “mystical and grounded” aesthetic, where one might occasionally glimpse the phantom caress of a brushstroke (or its digital equivalent, the effect is what matters), means a deceptively simple line can carry the weight of a philosophical treatise.

Hélène and her cohort are not mere figures in a landscape; they are porous, at times seeming to absorb the very chroma of their surroundings. The departed Manon and Marc, by contrast, often manifest as beautifully unsettling ectoplasmic outlines – less characters in the traditional sense, more resonant echoes against the backdrop of Hélène’s unravelling world, further blurring the already thin membrane between solid being and shifting backdrop.

The palette is a mood ring for the soul, a carefully curated visual lexicon designed to articulate the unspoken. Reds and blacks scream of trauma and the visceral, fragmented memory of violence; earthy greens and beiges whisper of Hélène’s fragile, evolving connection to the natural world (or what remains of it, anyway). Manon, in her spectral fury and unwavering conviction, often bathes in a coppery, almost infernal glow, a stark visual counterpoint to the porcelain sterility emanating from the establishment’s ivory tower.

And that infamous yellow blood – an inspired, jarring stroke of defiance against visual cliché, turning every gunshot into an aesthetic question mark as much as a narrative punctuation. These are not just pretty pictures, mind you; they’re emotional weather reports, guiding us through Hélène’s internal tempests with deft shifts in hue and a dramatic play of light and shadow that feels almost Rembrandtesque at times, if Rembrandt had been an anxious 21st-century animator with a penchant for existential dread.

Symbolism, naturally, is baked into the very pigment. The lush, almost aggressively textured wilderness – you can practically smell the damp earth and decaying leaves – fights a constant visual battle with the manicured, sterile opulence of the oppressors (no prizes for guessing where the film’s sympathies lie; hint: it’s with the dirt and the trees, not the gilded cages).

Those golden statues, first seen gleaming in the antagonists’ palatial grounds, act as silent, smirking commentators throughout – wolves, sheep, the whole allegorical menagerie, their fixed forms a mockery of the fluid, messy lives unfolding around them. A literal tidal wave of rewilding earth doesn’t just suggest societal upheaval; it positively bellows it from the screen in a moment of breathtaking, terrifying transformation. Even the acts of violence, stylized as they are, retain a visceral punch, a painterly brutality.

And those “cosmic flower-covered animal cadavers,” imagery straight out of some beautiful, eco-goth nightmare, hint at a cycle of decay and startling regeneration that’s both deeply unsettling and, perversely, shot through with a strange, almost alien kind of hope. The entire visual grammar conspires to create this sustained, oneiric hum, making the film less a narrative to be passively followed and more a psychic state to be inhabited, where reality frays at the edges and all established boundaries seem like mere, flimsy suggestions.

Navigating the Wreckage of What We Believe

At its thorny heart, “Death Does Not Exist” stages a Socratic dialogue with shattered ideals and the ghosts of good intentions. It prods that eternal, uncomfortable tug-of-war between social responsibility (whatever that means in a world so demonstrably fractured) and the rather more primal urge for self-preservation, especially when bullets, even aesthetically intriguing yellow ones, are in play.

The film scrutinizes both the potent fantasy and the profound limitations of individual and collective action, particularly when that action involves making things go boom with righteous, if ultimately naive, conviction. It doesn’t offer a neat verdict on revolutionary violence, presenting it less as a clear solution and more as another form of complicated human weather – sometimes a cleansing storm, often just a drizzle of tragic miscalculations leading to a downpour of regret. This resolute refusal to wag a moral finger is either its profound strength or its maddening ambiguity, depending on your tolerance for irresolution (and perhaps how much sleep you’ve had).

Hélène’s woodland wanderings serve as a masterclass in guilt-marination, her psyche the proving ground for enduring questions of redemption. Manon’s spectral offer of a “second chance” hangs heavy with portent – is it a genuine path to absolution, a deeper descent into the ideological mire, or simply the universe’s idea of a very bleak, beautifully animated joke? The film seems to breathe the question of whether cycles of violence and failure are truly breakable, or if humanity is doomed to repeat its most spectacular blunders, perhaps just with more aesthetically pleasing collateral damage next time. (A question many societies are currently asking themselves, with varying degrees of suppressed panic and a lot of shouting on the internet.)

Unsurprisingly, the film is steeped in our current Age of Anxiety (™ pending, though the patent office for zeitgeist terms is notoriously slow). It mainlines the societal hum of grotesque inequality, pervasive ecological dread, and the gnawing sense that the adults have comprehensively fumbled the generational football.

The personal cost of caring, of attempting any meaningful intervention in such a broken system, is laid bare with unflinching, almost cruel honesty. Freedom, choice, how to proceed when the map is demonstrably on fire – the film lobs these existential grenades without providing defusal instructions. Manon’s quietly devastating line, “Life… It’s a movement, and a movement has a cost, inevitably,” serves as a beautifully bleak thesis statement for the entire haunting affair.

So, is there hope? Perhaps. But it’s a bruised, limping, heavily bandaged sort of hope, not the shiny, inspirational poster kind often peddled when real solutions are too difficult. The film finds a strange, disquieting beauty in the wreckage, in the uncanny resurrection of a savaged sheep or the spectral reanimation of fallen comrades – life and death entwined in a möbius strip of consequence and recurrence.

Easy answers are notably absent; the film is profoundly allergic to them. Its significant power, particularly in its deliberate refusal to flesh out the specifics of the activists’ grievances or the oppressors’ particular brand of villainy, lies in this allegorical reach. While some might find this frustratingly vague, I’d argue it transforms the narrative from a singular, localized story into a broader, more unsettling, and ultimately more resonant meditation on the perennially messy, often tragic business of trying to violently birth a utopia from the unyielding clay of dystopia. History, after all, is littered with such noble, bloody, and inevitably complicated failures.

Full Credits

Director: Félix Dufour-Laperrière

Writer: Félix Dufour-Laperrière

Cast: Karelle Tremblay, Barbara Ulrich, Zeneb Blanchet, Mattis Savard-Verhoeven, Irène Dufour

Producers: Pierre Baussaron, Félix Dufour-Laperrière, Nicolas Dufour-Laperrière, Emmanuel-Alain Raynal

Composer: Jean L’Appeau

The Review

Death Does Not Exist

An exquisitely animated, philosophically dense dive into the messy heart of activism, guilt, and societal collapse, "Death Does Not Exist" is less a story savoured than a haunting atmosphere inhaled. It offers no comforting resolutions, only beautifully rendered, uncomfortable questions that linger like its spectral figures. A challenging, often unsettling, yet undeniably potent piece of cinema for those willing to wrestle with its ambiguities. It’s a stark, necessary meditation for our fractured times.

PROS

- Boasts a stunning and distinctive hand-drawn animation style, rich with symbolic imagery and a powerful use of colour.

- Delves into profound, complex themes concerning activism, guilt, societal collapse, and the ambiguous nature of violence.

- Creates a haunting, dreamlike, and potent experience, masterfully weaving sound and visuals to immerse the viewer.

- Presents an original and challenging cinematic vision that eschews easy answers for thought-provoking inquiry.

- Features exceptional sound design and a restrained yet unsettling score that perfectly complements its eerie, reflective mood.

CONS

- The storyline can be deliberately vague and open to interpretation, potentially leaving viewers desiring more concrete resolutions or character motivations.

- Its non-linear, dreamlike progression and contemplative pacing might not appeal to all, potentially feeling slow or repetitive to some.

- The sheer number of heavy ideas and symbolic layers, while rich, could feel overwhelming or overly ponderous for some viewers.

- The stylized approach and allegorical nature might create a certain emotional distance for those seeking more direct character engagement.