Do swidaniya Vlad? Which translates as Goodbye, Vladimir? That is what analysts are now asking because of the ever-worsening stuff for Russian President Vladimir Putin, especially since the start of the Ukraine war.

It was more than 20 years ago that Boris Yeltsin, already visibly frail at the time, nominated him as prime minister and designated successor as head of the Kremlin. Since then, the now 69-year-old has been prime minister, president, prime minister and president again and again – for the Russian constitution has a limit on how long the state can stay in office.

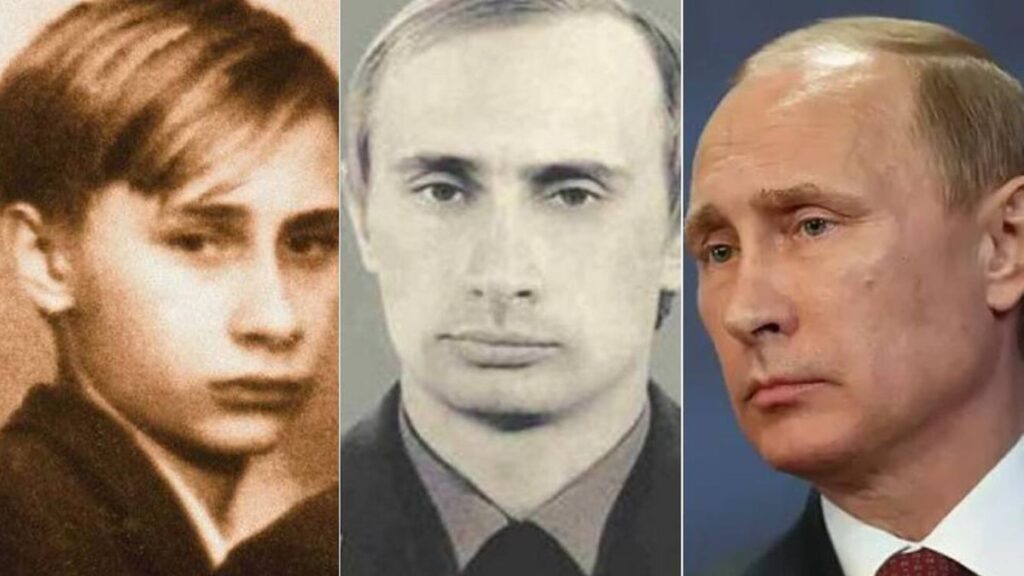

Not even he himself expected that Putin would ever reach the highest offices. He grew up as a boy in a working-class family in a Leningrad backyard. His mother endured the nearly 900-day blockade by Hitler’s Wehrmacht in the Neva city.

To fight back against the strong guys, Mr Sutka learned judo, and after school, joined the KGB at an early age. Until the fall of the GDR, He served with the Soviet intelligence service in Dresden. In 1990, Mr KGB’s first job after that was at Leningrad State University, supervising Western study-abroad students.

Only a year later, he moved to City Hall, became deputy to Mayor Anatoly Sobchak, at a time when press writers campaigned for change from Gorbachev to Yeltsin, from the Soviet Union to Russia, and for Leningrad to be renamed back to St. Petersburg, and organized sit-ins in front of Putin’s and Sobchak’s offices.

He was still a long way from Moscow then and even further from the highest office in the state. After arriving in the Kremlin, he was making trips to Fidel Castro’s Cuba and to China. During his first two and a half years in office, he tidied up what his predecessor Yeltsin had left undone: Fundamental tax reforms, privatization of land or reform of corporate law.

Putin has consolidated the state that threatened to fall apart under Yeltsin, not least through relentless campaigns against the separatist Caucasus republic of Chechnya. He also increased state revenues thanks to his “flat tax” uniform tax rate. He was thus able to pay wages and pensions on time and even gradually increase them. Putin became – with former Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev as head of Gazprom’s supervisory board and today’s head of Sberbank, Herman Gref, as minister of the economy – the reformer-in-chief.

Until Yukos’ fall from grace in 2003, in which Putin had the disagreeable oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky imprisoned and drove the country’s second-largest oil producer into bankruptcy. The state oil giant Rosneft took over its much more agile private rival.

After media oligarchs Boris Berezovsky and Vladimir Gussinsky had already fled and former oligarch Khodorkovsky had to endure almost ten years in prison, most major entrepreneurs gave up their own ambitions, submitted themselves to the Kremlin or, like jet-setting billionaire Roman Abramovich (Chelsea FC), voluntarily signed a contract with state-owned companies. Under Yeltsin, the strong and pluralistic media came under Kremlin control.

Discussion about this post